Reading: The Early Reformation and Martin Luther

Christopher Brooks

The Protestant Reformation was the permanent split within the Catholic church that resulted in multiple competing denominations (versions, essentially) of Christian practice and belief. From the perspective of the Catholic hierarchy, these new denominations – lumped together under the category of “Protestant” – were nothing more or less than new heresies, sinful breaks with the correct, orthodox beliefs and practices of the Church. The difference between Protestant churches and earlier heretical movements was that the Church proved unable to stamp them out or re-assimilate them into mainstream Catholic practice. Thus, what began as a protest movement against corruption within the Church very quickly evolved into a number of widespread and increasingly militant branches of Christianity itself.

Ironically, “the” Reformation as the sundering of Christian unity was at least in part the product of prosaic reformations already occurring within the Church. The founding figure of the Protestant Reformation, Martin Luther, used the humanistic education that had become increasingly common for members of the Church in formulating his arguments. Many early adopters of Protestantism were drawn to the new movement because they were already enthusiastic supporters of church reform. In part as a reaction to Protestantism but also in part as an extension of pre-existing reform movements, the Catholic hierarchy would go on to introduce important changes to both practice (e.g. colleges that trained priests) and culture (e.g. a new focus on the spiritual life of the common person) that did amount to meaningful reforms. These changes were long referred to as the “Counter-Reformation,” but are now recognized by historians as constituting a Catholic Reformation that was more than just an anti-Protestant reaction.

The Context of the Reformation

The context of the Reformation was the strange state of the Catholic Church as of the late fifteenth century. The Church was omnipresent in early-modern European society. About one person in seventy-five was part of the Church, as a priest, monk, nun, or member of a lay order. Practically every work of art depicted biblical themes. The Church supervised births, marriages, contracts, wills, and deaths – all law was, by implication, the law of God Himself. Furthermore, in Catholic doctrine, spiritual salvation was only accessible through the intervention of the Church; without the rituals (sacraments) performed by priests, the soul was doomed to go to hell. Finally, popes fought to claim the right to intervene in secular affairs as they saw fit, although this was a fight they rarely won, losing even more ground as the new more powerful and centralized monarchies rose to power in the fifteenth century.

Simply put, as of the Renaissance era, all was not well with the Church. The Babylonian Captivity and the Great Western Schism both undermined the Church’s authority. The stronger states of the period claimed the right to appoint bishops and priests within their kingdoms, something that the monarchs of England and France were very successful in doing. This led both laypeople and some priests themselves to look to monarchs, rather than the pope, for patronage and authority.

At the same time, elite churchmen (including the popes themselves) continued to live like princes. The papacy not only set a bad example, but attempts to reform the lifestyles and relative piety of priests generally failed; the papacy was simply too remote from the everyday life of the priesthood across Europe, and since elite churchmen were all nobles, they usually continued to live like nobles. In many cases, they openly lived with concubines, had children, and worked to ensure that their children receive lucrative positions in the Church. Laypeople were well aware of the slack morality that pervaded the Church. Medieval and early-modern literature is absolutely shot through with satirical tracts mocking immoral priests, and depictions of hell almost always featured priests, monks, and nuns burning alongside nobles and merchants.

These patterns affected monasticism as well. The idea behind monastic orders had been imitating the life of Christ, yet by the early modern period, many monasteries (especially urban ones) ran successful industries, and monks often lived in relative luxury compared to townspeople. Furthermore, the monasteries had been very successful in buying up or receiving land as gifts; by the late fifteenth century a full 20% of the land of the western kingdoms was owned by monasteries. The contrast between the required vow of poverty taken by monks and nuns and the wealth and luxury many monks and nuns enjoyed was obvious to laypeople.

The result of this widespread concern with corruption was a new focus on the inner spiritual life of the individual, not the focus on and respect for the priest, monk, or nun. New movements sprung up around Europe, including one called Modern Devotion in the Netherlands, that focused on moral and spiritual life of laypeople outside of the auspices of the Church. The handbook of the Modern Devotion was called The Imitation of Christ, written in the mid-fifteenth century and published in various editions after that, which was so popular that its sales matched those of the Bible at the time. It promoted the idea of salvation without needing the Church as an intermediary at all.

Within the Church, there were widespread and persistent calls for reform to better address the needs of the laity and to better live up to the Church’s own moral standards. Numerous devout priests, monks, and nuns abhorred the corruption of their peers and superiors in the Church and called for change – the Spanish branch of the Church enjoyed a strong period of reform during the fifteenth century, for example. Despite this reforming zeal within the Church and the growing popularity of lay movements outside of it, however, almost no one anticipated a permanent break from the Church’s hierarchy itself.

Lutheranism

Martin Luther (1483 – 1546) was a German monk who endured a difficult childhood and a fraught relationship with his father. He suffered from bouts of depression and anxiety that led him to become a monk, the traditional solution to an identity crisis as of the early modern period. Luther received both a scholastic and a humanistic education, eventually becoming a professor at the small university in the city of Wittenberg in the Holy Roman Empire. There, far from the centers of both spiritual and secular power, he contemplated the Bible, the Church, and his own spiritual salvation.

Luther struggled with his spiritual identity. He was obsessively afraid of being damned to hell, feeling totally unworthy of divine forgiveness and plagued with doubt as to his ability to achieve salvation. The key issue for Luther was the concept of good works, an essential element of salvation in the early-modern church. In Catholic doctrine, salvation is achieved through a combination of the sacraments, faith in God, and good works, which are good deeds that merit a person’s admission into heaven. Those good works could be acts of kindness and charity, or they could be gifts of money to the Church – a common “good work” at the time was leaving money or land to the Church is one’s will. Luther felt that the very idea of good works was ambiguous, especially because works seemed so inadequate when compared to the wretched spiritual state of humankind. He could not understand how anyone merited admittance to heaven no matter how many good works they carried out while alive – the very idea seemed petty and base compared to the awesome responsibility of living up to Christianity’s moral standards.

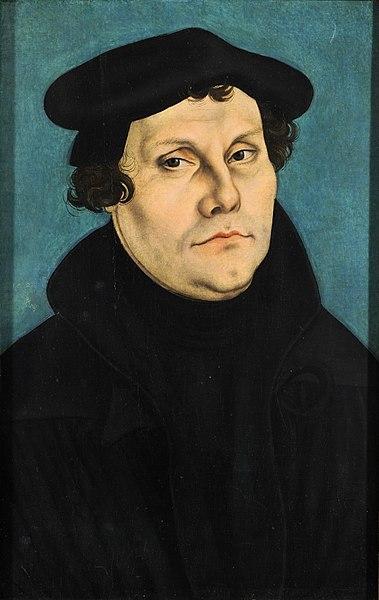

A 1528 portrait of Luther.

In about 1510 Luther began to explore a possible answer to this quandary: the idea that salvation did not come from works, but from grace, the limitless love and forgiveness of God, which is achievable through faith alone. Over time, Luther developed the idea that it takes an act of God to merit a person’s salvation, and the reflection of that act is in the heartfelt faith of the individual. A person’s willed attempts to do good things to get into heaven were always inadequate; what mattered was that the heartfelt faith of a believer might inspire an infinite act of mercy on the part of God. This idea – salvation through faith alone – was a major break with Catholic belief.

This concept was potentially revolutionary because in one stroke it did away with the entire edifice of church ritual. If salvation could be earned through faith alone, the sacraments were at best symbolic rituals and at worst distractions – over time, Luther argued that only baptism and communion were relevant since they were very clearly inspired by Christ’s actions as described in the New Testament. In Luther’s vision, the priest was nothing more than a guide rather than a gatekeeper who could grant or withhold the essential rituals, and a believer should be able to read the Bible directly rather than be forced to defer to the priesthood.

Having developed the essential points of his theology, Luther then confronted what he regarded as the most blatant abuse of the Church’s authority: indulgences. In 1517, Pope Leo X issued a new indulgence to fund the building of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Luther was incensed at how crass the sale of indulgences was (it was as bad as a carnival barker’s act in nearby Wittenberg) and at the fact that this new indulgence promised to absolve the purchaser of all sins, all at once. Furthermore, the indulgence could be purchased on behalf of those who were already dead and “spring” them from purgatory in one fell swoop. Luther responded by posting a list of ninety-five attacks against indulgences to the door of the Wittenberg cathedral. These “95 Theses” are considered by historians to be the first official act of the Protestant Reformation.

The 95 Theses were relatively moderate in tone. They attacked indulgences for leading to greed instead of piety, for leading the laity to distrust the Church, and for simply not working – they did not, Luther argued, absolve the sins of those who purchased them. Written in Latin, the 95 Theses were intended to spark debate and discussion within the Church. And, while he criticized the pope’s wealth and (implied) greed, Luther did not attack the office of the papacy itself. It should be emphasized that calls for reform within the Church were nothing new, and Luther certainly saw himself as a would-be reformer at this stage, not a revolutionary. Soon, however, the 95 Theses were translated into German and reprinted, which led to an unexpected and, at least initially, unwanted celebrity.

Luther’s position continued to radicalize after 1521. He claimed that the pope was, in fact, the Anti-Christ foretold in the Book of Revelations, and he came to believe that he was living in the End Times. He also personally translated the Bible into German and he happily met with his ever-growing group of followers. Initially a slur against heretics, the term “Protestant” was soon embraced by those followers, who used it as a defiant badge of honor.

Very quickly, Protestantism caught on across the empire, especially among elites, churchmen, and the educated urban classes. In the 1520s most Lutherans were reform-minded clerics, regarding Luther’s movement as an effective and radical protest against all of the problems that had plagued the Church for centuries. Part of the appeal of Lutheranism to priests was that it legitimized the lifestyle many of them were already living; they could get married to their concubines and acknowledge their children if they left the Church, which droves of them did starting in the 1520s. Thanks both to the perceived purity of its doctrine and the support of rulers, nobles, and converted priests, Lutheranism started spreading in earnest among the general population starting in the 1530s.

Charles V was in an unenviable position. As Holy Roman Emperor, he felt bound to defend the Church, but he could not do so through force of arms. He spent most of his reign fighting against both France and the Ottoman Empire, which were among the greatest powers of the era. Thus, in 1526 he allowed the German princes to choose whether or not to enforce his ban on Lutheranism as they saw fit, in hopes that they would continue to offer him their military assistance – he tried unsuccessfully to repeal this reluctant tolerance in 1529, but it was too late. Practically speaking, the German states ended up being divided roughly evenly, with a concentration of Lutheranism in the north and Catholicism in the south.

Luther was elated by the success of his message; he happily accepted the use of the term “Lutheranism” to describe the new religious movement he had started, and he felt certain that the correctness of his position was so appealing that even the Jews would abandon their traditional beliefs and convert (they did not, and Luther swiftly launched a vituperative anti-Semitic attack entitled Against the Jews and their Lies). Much to his chagrin, however, Luther watched as some groups who considered themselves to be Lutherans took his message in directions of which he completely disapproved.

Luther himself was a deeply conservative man. His attack on Catholic doctrine was fundamentally based on what he saw as a “return” to the original message of the Bible. Many Protestants interpreted his message as indicating that true Christians were only accountable to the Bible and could therefore reject the existing social hierarchy as well. In 1524, an enormous peasant uprising occurred across Germany, inspired by this interpretation of Lutheranism and demanding a reduction in feudal dues and duties, the end of serfdom, and greater justice from feudal lords. In 1525, Luther penned a venomous attack against the rebels entitled Against the Thieving, Murderous Hordes of Peasants which encouraged the lords to slaughter the peasants like dogs. The revolt was put down brutally, with over 100,000 killed, and Lutheranism was able to keep the support of the elites like Frederick the Wise who sheltered it.

Still, the uprising indicated that the movement Luther had begun was not something he could control, despite his best efforts. The very nature of breaking with a single authoritarian institution brought about a number of competing movements, some of which were directly inspired by and connected to Luther, but many of which, soon, were not.

Calvinism

The most important Protestant denomination to emerge after the establishment of Lutheranism was Calvinism. Jean Calvin, a French lawyer exiled for his sympathy with Protestantism, settled in Geneva, Switzerland in 1536. Calvin was a generation younger than Luther, and hence was born into a world in which religious unity had already been fragmented; in that sense, the fact that he had Protestant views is not as surprising as Luther’s break with the Church had been. In Geneva, Calvin began work on Christian theology and soon formed close ties with the city council. The result of his work was Calvinism, a distinct Protestant denomination that differed in many ways from Lutheranism.

Calvin accepted Luther’s insistence on the role of faith in salvation, but he went further. If God was all-powerful and all-knowing, and he chose to extend his grace to some people but not to others, Calvin reasoned, it was folly to imagine that humans could somehow influence Him. Not only was the Catholic insistence on good works wrong, the very idea of free will in the face of the divine intelligence could not be correct. Calvin noted that only some parishioners in church services seemed to be able to grasp the importance and complexities of scripture, whereas most were indifferent or ignorant. He concluded that God, who transcended both time and space, chose some people as the “elect,” those who will be saved, before they are even born. Free will is merely an illusion born of human ignorance, since the fate of a person’s soul was determined before time itself began. This doctrine is called “predestination,” and while the idea of the absence of free will and predetermined salvation may seem absurd at first sight, in fact it was simply the logical extension of the very concept of divine omnipotence according to Calvin.

Sixteenth-century portrait of Calvin. Austere black clothing became associated with Calvinists, who rejected ostentatious dress and decoration.

While Lutheranism spread to northern Germany and the Scandinavian countries, Calvinism caught on not just in Switzerland, but in France (where Calvinists were known as Huguenots) and Scotland, where the Scottish Calvinists became known as Presbyterians. Everywhere, Calvinists set themselves apart by their plain dress and their dour outlook on merriment, celebrations, and the pleasures of the flesh. The best known Calvinists in the American context were the Puritans, English Calvinists who left Europe (initially fleeing persecution) to try to create a perfect Christian community in the New World.

It should be emphasized that Lutherans and Calvinists quickly came to regard one another as rivals, even enemies, rather than as “fellow” Protestants. Luther and Calvin came to detest one another, finding each other’s respective theology as flawed and misleading as that of Catholicism. While some pragmatic alliances between Protestant groups would eventually emerge because of persecution or war, for the most part each Protestant denomination claimed to have exclusive access to religious truth, regarding all others as hopelessly ignorant and, in fact, damned to hell.

The Catholic Reaction

Initially, most members of the Church hierarchy were overwhelmed and bewildered by the emergence of Protestantism. All of the past heresies had remained limited in scope as compared with the incredible rapidity with which Lutheranism spread. For practical political reasons, the pope and various rulers were either unwilling or unable to use force to crack down on Protestantism at first, as witnessed with Charles V’s failed attempts to curtail Lutheranism’s spread. Lutheranism also spread much more quickly than had earlier heresies, which tended to be limited to certain regions; here, the fact that Luther and his followers readily embraced the printing press to spread their message made a major impact, with word of the new movement spreading across Europe over the course of the 1520s.

In historical hindsight, the shocking aspect of the Catholic Church’s initial reaction to the emergence of Protestantism is that there was no reaction. For decades, popes remained focused on the politics of central Italy or simply continued beautifying Rome and enjoying a life of luxury; this was the era of the “Renaissance popes,” men from elite families who regarded the papal office as little more than a political position that happened to be at the head of the Church. Likewise, there was no widespread awareness among most Church officials that anything out of the ordinary was taking place with Luther; despite the radicalism of his position, most of the clergy assumed that Lutheranism was a “flash in the pan,” doomed to fade back into obscurity in the end. By the 1540s, however, church officials began to take the threat posed by Protestantism more seriously.

The initial period of Catholic Reformation, from about 1540 – 1550, was a fairly moderate one that aimed to bring Protestants back into the fold. In a sense, the very notion of a permanent break from Rome was difficult for many people, certainly many priests, to conceive of. After about 1550, however, when it became clear that the split was permanent, the Church itself became much more hardline and intolerant. The subsequent reforms were as much about imposing a new internal discipline as they were in making membership appealing to lay Catholics.

The same factors that had made the Church difficult to reform before the Protestant break made it strong as an institution that opposed the new Protestant denominations: habit, ritual, organization, discipline, hierarchy, and wealth all worked to preserve the Church’s power and influence. Likewise, many princes realized that Protestantism often led to political problems in their territories; even though many of the German princes had originally supported Luther in order to protect their own political independence, many others came to realize that the last thing they wanted were independent-minded denominations in their territories, some of which might reject their worldly authority completely (as had the German peasants who rose up in 1524).

Among Catholics at all levels of social hierarchy, Catholic rituals were comforting, and even though rejecting the excesses in Catholic ritual had been part of the appeal of Protestantism to some, to many others it was precisely those familiar rituals that made Catholicism appealing. The Catholic Reformation is often associated with the “baroque” style of art and music which encouraged an emotional connection with Catholic ritual and, potentially, with the experience of faith itself. The Church continued to fund huge building projects and lavish artwork, much of which was aimed to appeal to laypeople, not just serve as pretty decorations for high-ranking churchmen.

Likewise, there was a wave of Protestant conversions that spread very rapidly by the 1530s, but then as the Protestant denominations splintered off and turned on one another, the “purity” of the appeal of Protestantism faded. In other words, when Protestants began fighting each other with the same vigor as their attacks on Rome, they no longer seemed like a clear and simple alternative to Roman corruption.

Conclusion

The battle lines between Protestantism and Catholicism were firmly set by the 1560s. The Catholic Reformation established Catholic orthodoxy and launched a massive, and largely successful, campaign to re-affirm the loyalty and enthusiasm of Catholic laypeople. Meanwhile, Protestant leaders were equally hardened in their beliefs and actively inculcated devotion and loyalty in their followers. Nowhere was there the slightest notion of “religious tolerance” in the modern sense – both sides were convinced that anyone and everyone who disagreed with their spiritual outlook was damned to an eternity of suffering. The wars of propaganda and evangelism gave way to wars of muskets and pikes soon enough.

Image Citations (Wikimedia Commons):

Luther – Public Domain

Diet of Worms – Public Domain

Calvin – Public Domain

This chapter has been derived with modifications from Chapter 6: Reformations in Western Civilization: A Concise History.