Reading: The Classical Age of Greece

Christopher Brooks

Introduction

The most frequently studied period of Greek history is the “Classical Age,” the time between the triumph of the Greek coalition against Persia in 479 BCE and the conquest of Greece by the Macedonian king Philip II (the father of Alexander the Great) in 338 BCE. This was the era in which the Greek poleis were at their most powerful economically and militarily and their most innovative and productive artistically and intellectually. While opinions will vary, perhaps the single most memorable achievement of the Classical Age was in philosophy, first and foremost because of the thought of the most significant Greek philosophers of all time: Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. The Classical Age (like the European Renaissance about two thousand years later) is best remembered for its artistic and intellectual achievements rather than the political events of the time.

The Peloponnesian War

When the Spartans and Athenians led the Greek poleis to victory against the Persians in the Persian War, it was a shock to the entire region of the Mediterranean and Middle East. Persia was the regional “superpower” at the time, while the Greeks were just a group of disunited city-states on a rocky peninsula to the northwest. After their success, the Greeks were filled with confidence about the superiority of their own form of civilization and their taste for inquiry and innovation. Greeks in this period, the Classical Age, produced many of their most memorable cultural and intellectual achievements.

The great contrast in the Classical Age was between the power and splendor of the Greek poleis, especially Athens and Sparta, and the wars and conflicts that broke out as they tried to expand their power and control. After the defeat of the Persians, the Athenians created the Delian League, in theory a defensive coalition that existed to defend against Persia and to liberate the Ionian colonies still under Persian control, but in reality a political tool eventually used by Athens to create its own empire.

Each year, the members of the Delian League contributed money to build and support a large navy, meant to protect all of Greece from any further Persian interference. Athens, however, quickly became the dominant player in the Delian League. Athens was able to control the League due to its powerful navy; no other polis had a navy anywhere near as large or effective, so the other members of the League had to contribute funds and supplies while the Athenians fielded the ships. Thus, it was all too easy for Athens to simply use the League to drain the other poleis of wealth while building up its own power. The last remnants of Persian troops were driven from the Greek islands by 469 BCE, about ten years after the great Greek victories of the Persian War, but Athens refused to allow any of the League members to resign from the League after the victory.

Soon, Athens moved from simply extracting money to actually imposing political control in other poleis. Athens stationed troops in garrisons in other cities and forced the cities to adopt new laws, regulations, and taxes, all designed to keep the flow of money going to Athens. Some of the members of the League rose up in armed revolts, but the Athenians were able to crush the revolts with little difficulty. The final event that eliminated any pretense that the League was anything but an Athenian empire was the failure of a naval expedition sent in 460 BCE by Athens to help an Egyptian revolt against the Persians. The Greek expedition was crushed, and the Athenians responded by moving the treasury of the League, formerly kept on the Greek island of Delos (hence “Delian League”), to Athens itself, arguing that the treasury was too vulnerable if it remained on Delos. At this point, no other member of the League could do anything about it – the League existed as an Athenian-controlled empire, pumping money into Athenian coffers and allowing Athens to build some of its most famous and beautiful buildings. Thus, the great irony is that the most glorious age of Athenian democracy and philosophy was funded by the extraction of wealth from its fellow Greek cities. In the end, the Persians simply made peace with Athens in 448 BCE, giving up the claim to the Greek colonies entirely and in turn eliminating the very reason the League had come into being.

Meanwhile, Sparta was the head of a different association, the Peloponnesian League, which was originally founded before the Persian War as a mutual protection league of the Greek cities of Corinth, Sparta, and Thebes. Like Athens, Sparta dominated its allies, although it did not take advantage of them in quite the same ways that Athens did. Sparta was resentful and, in a way, fearful of Athenian power. Open war finally broke out between the two cities in 431 BCE after two of their respective allied poleis started a conflict and Athens tried to influence the political decisions of Spartan allies. The war lasted from 431 – 404 BCE.

The Spartans were unquestionably superior in land warfare, while the Athenians had a seemingly unstoppable navy. The Spartans and their allies repeatedly invaded Athenian territory, but the Athenians were smart enough to have built strong fortifications that held the Spartans off. The Athenians, in turn, attacked Spartan settlements and positions overseas and used their navy to bring in supplies. While Sparta could not take Athens itself, Athens was essentially under siege for decades; life went on, but it was usually impossible for the Athenians to travel over land in Greece outside of their home region of Attica.

Athens and its allies, including the poleis it dominated in the Delian League, are depicted in orange, Sparta and its allies in green.

Truces came and went, but the war continued for almost thirty years. In 415 BCE Athens suffered a disaster when a young general convinced the Athenians to send thousands of troops against the city of Syracuse (a Spartan ally) in southern Sicily, hundreds of miles from Greece itself, in hopes of looting it. The invasion turned into a nightmare for the Athenians, with every ship captured or sunk and almost every soldier killed or captured and sold into slavery; this dramatically weakened the Athenian military.

At that point, the Athenians were on the defensive. The Spartans established a permanent garrison within sight of Athens itself. Close to 20,000 slaves escaped from the Athenian silver mines that had originally paid for the navy before the Persian War and were welcomed by the Spartans as recruits (thus bolstering Spartan forces and cutting off Athens’ main source of revenue). Sparta finally struck a decisive blow in 405 BCE by surprising the Athenian fleet in Anatolia and destroying it. Athens had to sue for peace. Sparta destroyed the Athenian defenses it had used during the war, but did not destroy the city itself, and within a year the Athenians had created a new government.

The Aftermath

Greece itself was transformed by the Peloponnesian War. Both sides had sought out allies outside of Greece, with the Spartans ultimately allying with the Persians – formerly their hated enemies – in the final stages of the war. The Greeks as a whole were less isolated and more cosmopolitan by the time the war ended, meaning that at least some of their prejudices about Greek superiority were muted. Likewise, the war had inadvertently undermined the hoplite-based social and political order of the prior centuries.

Nowhere was this more true than in Sparta. Sparta had been greatly altered by the war, out of necessity becoming both a naval power and a diplomatic “player” and losing much of its former identity; some Spartans had gotten rich and were buying their sons out of the formerly-obligatory life in the barracks, while others were too poor to train. Likewise, the war had weakened Sparta’s cultural xenophobia and obsession with austerity, since controlling diplomatic alliances was as important as sheer military strength. Diplomacy required skill, culture, and education, not just force of arms. Subsequently, the Greeks as a whole were shocked in 371 BCE when the polis of Thebes defeated the Spartans three times in open battle, symbolically marching to within sight of Sparta itself and destroying the myth of Spartan invincibility.

Across Greece, the Poleis all adopted the practice of state-financed standing armies for the first time, rather than volunteer citizen-soldiers. Likewise, the poleis came to rely on mercenaries, many of whom (ironically) went on to serve the Persians after the war wound down. Thus, between 405 BCE – 338 BCE, the old order of the hoplites and republics atrophied, replaced by oligarchic councils or tyrants in the poleis and stronger, tax-supported states. The period of the war itself was thus both the high point and the beginning of the end of “classical” Greece. Meanwhile, Persia re-captured and exerted control over the Anatolian Greek cities by 387 BCE as Greece itself was divided and weakened. Thus, even though the Persians had “lost” the Persian War, they were as strong as ever as an empire.

Despite the importance of the Peloponnesian War in transforming ancient Greece, however, it should be emphasized that not all of the poleis were involved in the war, and there were years of truce and skirmishing during which even the major antagonists were not actively campaigning. The reason that this part of Greek history is referred to as the Classical Age is that its lasting achievements had to do with culture and learning, not warfare. The Peloponnesian War ultimately resulted in checking Athens’ imperial ambitions and causing the Greeks to broaden their outlook toward non-Greeks; its effects were as much cultural as political.

Athens and the Ironies of Democracy

Just as the Classical Age is nearly synonymous with “ancient Greece” itself, “ancient Greece” in the Classical Age is often conflated with what happened in Athens specifically. Athens was the richest and most influential of all of the Greek poleis during this period, although its power waned once it plunged into the Peloponnesian War against Sparta starting in 431 BCE. The most famous Greek philosophers – Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle – were either native Athenians (Socrates and Plato) or studied and taught in Athens (Aristotle). Likewise, the Athenian democracy that had crystallized under Cleisthenes, with about 10% of the overall population having a vote in public affairs, was at its height during this period.

The irony was not just that Athens reached its peak during the period of the Delian League and the wealth it extracted from other poleis, it was that Athenian democracy itself was at its strongest: even as it was forging an empire on top of the other city-states, Athens was becoming the first great experiment in democratic government in world history. The Athenian leader in charge during the transition to this phase was Pericles (495 – 429 BCE), an aristocrat who dominated Athenian politics but did not actually seize power as had the earlier tyrants.

When Pericles rose to be a dominant voice in Athenian politics, the system remained in place that had been set up by Cleisthenes. All adult male citizens had a vote in the public assembly, while a smaller council handled day-to-day business. Athenian citizens continued to pride themselves on their rhetorical skill, since everything hinged on the ability of public speakers to convince their fellows through strength of argumentative skill. The assembly also voted every year to appoint ten generals, who were in charge of both the military and foreign relations.

As the Delian League grew, which is to say as Athens took over control of its “allied” poleis, it increased the size of its bureaucracy accordingly. Under Pericles, there were about 1,500 officials who managed the taxation of the league’s cities, ran courts and administrative bodies, and managed the League’s activities. Pericles instituted the policy of paying public servants, who had worked for free in the past, a move that dramatically decreased the potential for corruption through bribes and opened the possibility of poorer citizens to serve in public office (i.e. before, a citizen had to be wealthy enough to volunteer in the city government – this meant that almost all farmers and small merchants were cut off from direct political power). He also issued a new law decreeing that only the children of Athenian parents could be Athenian citizens, a move that elevated the importance of Athenian women but also further entrenched the conceit of the Athenians in relation to the other Greek cities; the Athenians wanted citizenship to be their own, carefully protected, commodity. All of this suggests that Athens enjoyed a tremendous period of growth and prosperity, along with what was among the fairest and most impartial government in the ancient world at the time, but that it did so on the backs of its Greek “allies.”

There were further ironies present in the seeming egalitarianism of Greek society during the Classical Age. The Greeks were the first to carry out experiments in rationalistic philosophy and in democratic government. At the same time, Greek society itself was profoundly divided and unequal. First and foremost, women were held in a subservient position. Women, by definition, could not be citizens, even though in certain cases like the Athens of Pericles, they could assume an honored social role as mothers of citizens. Women could not hold public office, nor could they legally own property or defend themselves independently in court. They were, in short, legal minors (like children are in American society today) under the legal control and guardianship of their fathers or husbands.

For elite Greek women, social restrictions were stark: they were normally confined to the inner sanctums of homes, interacting only with family members or close female friends from families of the same social rank, and when they did go out in public they had to do so in the company of chaperones. There was never a time in which it was socially acceptable for an elite woman to be alone in public. Just about the only social position in which elite women had real, direct power was in the priesthoods of some of the Greek gods, where women could serve as priestesses. These were a very small minority, however.

Non-elite women had more freedom in the sense that they had to work, so they often sold goods in the marketplace or helped to run shops. Since the large majority of the Greek population outside of the cities themselves were farmers, women naturally worked alongside men on farms. Regardless, they did not have legal control over their own livelihoods, even if they did much of the actual work, with their husbands (or fathers or brothers) retaining complete legal ownership.

In almost all cases, Greek women were married off while extremely young, usually soon after puberty, and almost always to men significantly older than they were. Legal power over a woman passed from the father to the husband, and in cases of divorce it passed back to the father. Even in the case of widows, Greek tradition held that the husband’s will should dictate who his widow marry – most often another male member of his family, to keep the family property intact. One important exception to the absence of legal rights for women was that Greek women could initiate divorce, although the divorce would be recognized only after a legal process proved that the husband’s behavior was truly reprehensible to Greek sensibilities, and it was a rare occurrence either way: there is only one known case from classical Athens of a woman attempting to initiate divorce.

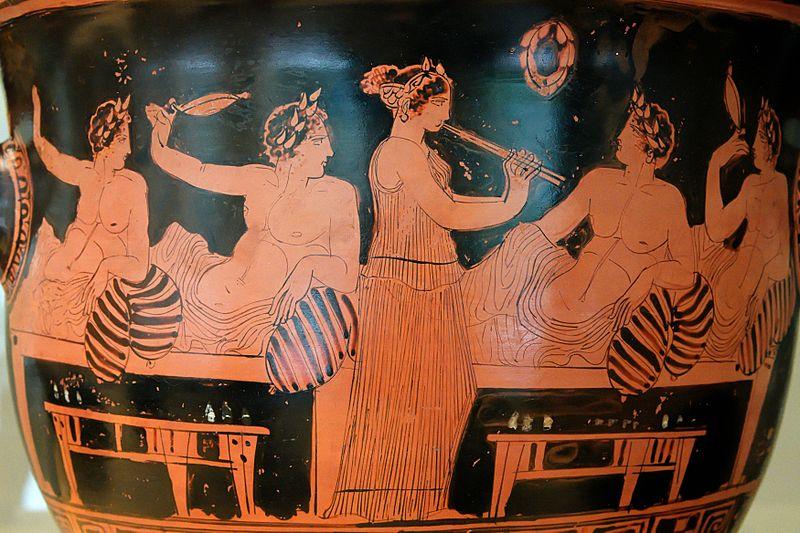

In the domestic sphere, there were physical divides between the front, public part of the house where men entertained their friends, and the back part of the house where women cared for the children and carried on domestic tasks like sewing. There was little tradition of mixed-sex socializing, outside of the all-male drinking parties called symposia that featured female “entertainers” – slaves and servants who carried on conversation, danced and sang, and had sex with the guests. In these cases, the female “company” was present solely for entertainment and sexual slavery.

Depiction of a symposium from c. 420 BCE, featuring a female entertainer – most likely a slave and obliged to provide sex as well as musical entertainment to the male guests.

In turn, prostitution was very common, with the bulk of prostitutes being slaves. Elite prostitutes were known as hetairai, who served as female companions for elite men and were supposed to be able to contribute to witty, learned discussion. One such hetairai, Aspasia, was the companion of Pericles and was a full member of the elite circle of philosophers, scientists, and politicians at the top of Athenian society. The difficulty in considering these special cases, however, is that they can gloss over the fact that the vast majority of women were in a disempowered social space, regarded as a social necessity that existed to bear children. An Athenian politician, Demosthenes, once said “we have hetairai for the sake of pleasure, regular prostitutes to care for our physical needs, and wives to bear legitimate children and be loyal custodians of our households.”

It is difficult to know the degree to which female seclusion was truly practiced, since all of the commentary that refers to it was written by elite men, almost all of whom supported the idea of female subservience and the separation of the sexes in public. What we know for sure is that almost no written works survive by women authors – the outstanding exception being Sappho, a poet of the Archaic period whose works suggests that lesbianism may have been relatively common (her home, the Greek island of Lesbos, is the root of the English word lesbian itself). Likewise, Greek legal codes certainly enforced a stark gender divide, and Greek homes were definitely divided into male-dominated public spaces and the private sphere of the family. There is at least some evidence, however, that gender divisions might not have been quite as stark as the male commentators would have it – as noted below, at least one Greek playwright celebrated the wit and fortitude of women in his work. Finally, we should note that major differences in gender roles were definitely present in different regions and between different poleis; regimented Sparta was far more progressive in its empowerment of women than was democratic Athens.

One product of the divide between men and women was the prevalence of bisexuality among elite Greek men (and, as suggested by Sappho’s work, also apparently among women). There was no concept of “heterosexual” versus “homosexual” in Greek culture; sexual attraction was assumed to exist, in potential, between men as easily as between men and women, although bisexuality appears to have been most common among men in the upper social ranks. One common practice was for an adult man of the elite classes to “adopt” a male adolescent of his social class and both mentor him in politics, social conduct, and war, and carry on what we would now regard as a statutory sexual relationship with him – this practice was especially common in the barracks society of Sparta.

Building on the prevalence of male relationships was the Greek tradition of male homosexual warriorhood, homosexual bonds between soldiers that helped them be more effective fighters. To cite a literary example, in Homer’s Iliad, the one event that rouses the mighty warrior Achilles to battle when he is busy sulking is the death of his (male) lover. In addition to the Spartan case noted above, another renowned historical example of homosexual warriorhood was the Sacred Band of the polis of Thebes, 150 male couples who led the army of Thebes and held the reputation of being completely fearless. Homosexual love in this case was linked directly to the Greek virtues of honor and skill in battle, as the Sacred Band were believed to fight all the harder in order to both honor and defend their lovers. This certainly seemed to be true at times, as when the Theban army, led by the Sacred Band, was the city that first defeated Sparta in open battle (this occurred after the Peloponnesian War, when Sparta found itself warring with its former allies like Thebes).

In addition to the dramatic gender disparities in Greek society, there was the case of slavery. Slaves in Greece were in a legal position just about as dire as any in history. Their masters could legally kill them, rape them, or maim them if they saw fit. Normally, slaves were not murdered outright, but this was because murder was seen as offensive to the gods, not because there were any legal consequences. As Greece became more wealthy and powerful, the demand for slaves increased dramatically as each poleis found itself in need of more labor power, so a major goal for warfare became the capturing of slaves. By 450 BCE, one-third of the population of Athens and its territories consisted of slaves.

Slaves in Greece came from many sources. While the practice was outlawed in Athens by Solon, most poleis still allowed the enslavement of their own people who were unable to pay debts. More common was the practice of taking slaves in war, and one of the effects of the Greek victories in the Persian War was that thousands of Persian captives were taken as slaves. There was also a thriving slave trade between all of the major civilizations of the ancient world; African slaves were captured and sold in Egypt, Greek slaves to Persia (despite its nominal ban on slavery, it is clear that at least some slavery existed in Persia), nomadic people from the steppes in Black Sea ports, and so on. With demand so high, any neighboring settlement was a potential source of slaves, and slavery was an integral part of the Mediterranean economy as a result.

Slavery was so prevalent that what the slaves actually did varied considerably. Some very lucky slaves who were educated ran businesses or served as bureaucrats, teachers, or accountants. In a small number of cases, such elite slaves were able to keep some of the money they made, save it, and buy their freedom. Much more common, however, were laborers or craftsmen of all kinds, who made things and then sold them on behalf of their masters. Slaves even served as clerks in the public bureaucracies, as well as police and guard forces in the cities. One exceptional case was a force of archers used as city guards in Athens who were slaves from Scythia (present-day Ukraine).

The worst positions for slaves were the jobs involving manual labor, especially in mines. As noted in the last chapter, one of the events that lost the Peloponnesian War for Athens was the fact that 20,000 of its publicly-owned slaves were liberated by the Spartans from the horrendous conditions in the Athenian silver mines. Likewise, there was no worse fate than being a slave in a salt mine (one of the areas containing a natural underground salt deposit). Salt is corrosive to human tissue in large amounts, and exposure meant that a slave would die horribly over time. The historical evidence suggests that slaves in mines were routinely worked to death, not unlike the plantation slaves of Brazil and the Caribbean thousands of years later.

Culture

If Greek society was thus nothing like present-day concepts of fairness or equality, what about it led to this era being regarded as “classical”? The answer is that it was during the Classical Age that the Greeks arrived at some of their great intellectual and cultural achievements. The Athenian democratic experiment is, of course, of great historical importance, but it was relatively short-lived, with democratic government not returning to the western world until the end of the eighteenth century CE. In contrast, the Greek approach to philosophy, drama, history, scientific thought, and art remained living legacies even after the Classical Age itself was at an end.

The fundamental concept of Greek thought, as reflected in drama, literature, and philosophy, was humanism. This was an overarching theme and phenomenon common to all of the most important Greek cultural achievements in literature, religion, drama, history-writing, and art. Humanism is the idea that, first and foremost, humankind is inherently beautiful, capable, and creative. To the Greek humanists, human beings were not put on the earth to suffer by cruel gods, but instead carried within the spark of godlike creativity. Likewise, a major theme of humanism was a pragmatic indifference to the gods and fate – one Greek philosopher, Xenophanes, dismissed the very idea of human-like gods who intervened in daily life. The basic humanistic attitude is that if there are any gods, they do not seem particularly interested in what humans do or say, so it is better to simply focus on the tangible world of human life. The Greeks thus offered sacrifices to keep the gods appeased, and sought out oracles for hints of what the future held, but did not normally pursue a deeply spiritual connection with their deities.

That being noted, one of the major cultural innovations of the Greeks, the creation of drama, emerged from the worship of the gods. Specifically, the celebrations of the god Dionysus, god of wine and revelry, brought about the first recognizable “plays” and “actors.” Not surprisingly, religious festivals devoted to Dionysus involved a lot of celebrating, and part of that celebration was choruses of singing and chanting. Greek writers started scripting these performances, eventually creating what we now recognize as plays. A prominent feature of Greek drama left over from the Dionysian rituals remained the chorus, a group of performers who chanted or sang together and served as the narrator to the stories depicted by the main characters.

Contemporary view of the remnants of the Greek theater of Lychnidos in present-day Macedonia. The upper tiers are still marked with the names of the wealthy individuals who purchased their own reserved seats.

Greek drama depicted life in human terms, even when using mythological or ancient settings. Playwrights would set their plays in the past or among the gods, but the experiences of the characters in the plays were recognizable critiques of the playwrights’ contemporary society. Among the most powerful were the tragedies: stories in which the frailty of humanity, most importantly the problem of pride, served to undermine the happiness of otherwise powerful individuals. Typically, in a Greek tragedy, the main character is a powerful male leader, a king or a military captain, who enjoys great success in his endeavors until a fatal flaw of his own personality and psyche causes him to do something foolish and self-destructive. Very often this took the form of hubris, overweening pride and lack of self-control, which the Greeks believed was offensive to the gods and could bring about divine retribution. Other tragedies emphasized the power of fate, when cruel circumstances conspired to lead even great heroes to failure.

In addition to tragedy, the Greeks invented comedy. The essential difference is that tragedy revolves around pathos, or suffering, from which the English word “pathetic” derives. Pathos is meant to inspire sympathy and understanding in the viewer. Watching a Greek tragedy should, the playwrights hoped, lead the audience to relate to and sympathize with the tragic hero. Comedy, however, is meant to inspire mockery and gleeful contempt of the failings of others, rather than sympathy. The most prominent comic playwright (whose works survive) was Aristophanes, a brilliant writer whose plays are full of lying, hypocritical Athenian politicians and merchants who reveal themselves as the frauds they are to the delight of audiences.

One famous play by Aristophanes, Lysistrata, was set in the Peloponnesian War. The women of Athens are fed up with the pointless conflict and use the one thing they have some power over, their bodies, to force the men to stop the fighting by withholding sex. A Spartan contingent appears begging to open peace negotiations because, it turns out, the Spartan women have done the same thing. Here, Aristophanes not only indulged in the ribald humor that was popular with the Greeks (even by present-day standards, Lysistrata is full of “dirty” jokes) but showed a remarkable awareness of, and sympathy for, the social position of Greek women. In fact, in plays like Lysistrata we see evidence that Greek women were not in fact always secluded and rendered mute by male-dominated society, even though (male) Greek commentators generally argued that they should be.

Greek drama, both tragedy and comedy, is of enormous historical importance because even when it used the gods as characters or fate as an explanation for problems, it put human beings front and center in being responsible for their own errors. It depicted human choice as being the centerpiece of life against a backdrop of often uncontrollable circumstances. Tragedy gave the Greeks the option of lamenting that condition, while comedy offered the chance of laughing at it. In the surviving plays of the ancient Greeks, there were very few happy endings, but plenty of opportunities to relate to the fate of, or make fun of, the protagonists. In turn, almost every present-day movie and television show is deeply indebted to Greek drama. Greek drama was the first time human beings acted out stories that were meant to entertain, and sometimes to inform, their audiences.

Science

The idea that there is a difference between “science” and “philosophy” is a very recent one, in many ways dating to the eighteenth century CE (i.e. only about 300 years ago). The word “philosophy” literally means “love of knowledge,” and in the ancient world the people we might identify as Greek “scientists” were simply regarded as philosophers by their fellow Greeks, ones who happened to be especially interested in how the world worked and what things were made of. Unlike earlier thinkers, the Greek scientists sought to understand the operation of the universe on its own terms, without simply writing off the details to the will of the gods.

The importance of Greek scientific work is not primarily in the conclusions that Greek scientists reached, which ended up being factually wrong most of the time. Instead, its importance is in its spirit of rational inquiry, in the idea that the human mind can discover new things about the world through examination and consideration. The world, thought the Greek scientists, was not some sacred or impenetrable thing that could never be understood; they sought to explain it without recourse to supernatural forces. To that end, Greek scientists claimed that things like wind, fire, lightning, and other natural forces, were not necessarily spirits or gods (or at least tools of spirits and gods), but might just be natural forces that did not have personalities of their own.

The first known Greek scientist was Thales of Miletus (i.e. Thales, and the students of his who went on to be important scientific thinkers as well, were from the polis of Miletus in Ionia), who during the Archaic Age set out to understand natural forces without recourse to references to the gods. Thales explained earthquakes not as punishments inflicted by the gods arbitrarily on humanity, but as a result of the earth floating in a gigantic ocean that occasionally sloshed it around. He traveled to Egypt and was able to measure the height of the pyramids (already thousands of years old) by the length of their shadows. He became so skilled at astronomy that he (reputedly) successfully predicted a solar eclipse in 585 BCE.

Thales had a student, Anaximander, who posited that rather than floating on water as his teacher had suggested, the earth was held suspended in space by a perfectly symmetrical balance of forces. He created the first known map of the world that attempted to accurately depict distances and relationships between places. Following Anaximander, a third scientist, Anaximenes, created the theory of the four elements that, he argued, comprise all things – earth, air, fire, and water. Many centuries later, Galen of Pergamon, a Greek physician living under Roman rule, would explain human health in terms of the balance of those four forces (the four “humors” of the body), ultimately crafting a medical theory that would persist until the modern era.

In all three cases, the significance of the Greek scientists is that they tried to create theories to explain natural phenomena based on what they observed in nature itself. They were employing a form of what is referred to as inductive reason, of starting with observation and moving toward explanation. Even though it was (at it turns out) inaccurate, the idea of the four elements as the essential building-blocks of nature and health remained the leading explanation for many centuries. Other Greek scientists came along to refine these ideas, most importantly when two of them (Leucippus and Democritus) came up with the idea that tiny particles they called atoms formed the elements that, in turn, formed everything else. It would take until the development of modern chemistry for that theory to be proved correct through empirical research, however.

History

It was the Greeks that came up with history in the same sense that the term is used today, namely of a story (a narrative) based on historical events that tries to explain what happened and why it happened the way it did. In other words, history as it was first written by the Greeks is not just about listing facts, it is about explaining the human motivations at work in historical events and phenomena. Likewise, the Greeks were the first to systematically employ the essential historical method of using primary sources written or experienced at the time as the basis of historical research.

The founding figure of Greek history-writing was Herodotus (484 – 420 BCE), who wrote a history of the Persian War that was acclaimed by his fellow Greeks. Herodotus sought to explain human actions in terms of how people tend to react to the political and social pressures they experienced. He applied his theory to various events in the ancient past, like the Trojan War, as well as those of Greece’s recent past. Most importantly, Herodotus traveled and read sources to serve as the basis of his conclusions. He did not simply sit in his home city and theorize about things; he gathered a huge amount of information about foreign lands and cultures and he examined contemporary accounts of events. This use of primary sources is still the defining characteristic of history as an academic discipline: professional historians must seek out writings and artifacts from their areas of study and use them as the basis for their own interpretations.

Herodotus also raised issues of ongoing relevance about the encounter of different cultures; despite the greatness of his own civilization, he was genuinely vexed by the issue of whether one set of beliefs and practices (i.e. culture) could be “better” than another. He knew enough about other cultures, especially Persia, to recognize that other societies could be as complex, and military more powerful, than was Greece. Nevertheless, his history of the Persian War continued the age-old Greek practice of referring to the Persians as “barbarians.”

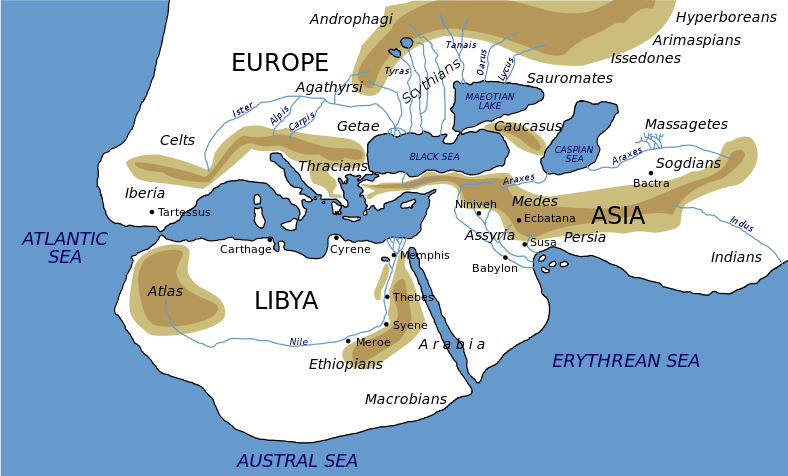

The world as described by Herodotus (the map is a contemporary image based on Herodotus’s work). Note the central position of Greece, just south of the region marked “Thracians.”

The other great Greek historian of the classical period was the Athenian writer Thucydides (460 – 404 BCE), sometimes considered the real “father” of history-writing. Thucydides wrote a history of the Peloponnesian War that remains the single most significant account of the war to this day. The work meticulously follows the events of the war while investigating the human motivations and subsequent decisions that caused events. The war had been a terrible tragedy, he wrote, because Athens became so power-hungry that it sacrificed its own greatness in the quest for more power and wealth. Thus, he deliberately crafted an argument (a thesis) and defended it with historical evidence, precisely the same thing historians and history students alike are expected to do in their written work. Thanks in part to the work of Herodotus and Thucydides, history became such an important discipline to the Greeks that they believed that Clio, one of the divine muses, the sources of inspiration for thought and artistic creation, was the patron of history specifically.

Philosophy

Perhaps the single greatest achievement of Greek thought was in philosophy. It was in philosophy that the Greeks most radically broke with supernatural explanations for life and thought and instead sought to establish moral and ethical codes, investigate political theory, and understand human motivations all in terms of the human mind and human capacities. As noted above, the word “philosophy” literally means “love of knowledge,” and Greek philosophers did much more than just contemplate the meaning of life; they were often mathematicians, physicists, and literary critics as well as “philosophers” in the sense that that the word is used in the present.

Among the important questions that most Greek philosophers dealt were those concerning politics and ethics. The key question that arose among the early Greek philosophers was whether standards of ethics and political institutions as they existed in Greece – including everything from the polis, democracy, tyranny, Greek standards of behavior, and so on – were somehow dictated by nature or were instead merely social customs that had arisen over time. The Classical Age saw the full flowering of Greek engagement with those questions.

Some of the early philosophers of the Greek classical age were the Sophists: traveling teachers who tutored students on all aspects of thought. While they did not represented a truly unified body of thought, the one common sophistic doctrine was that all human beliefs and customs were just habits of a society, that there were no absolute truths, and that it was thus vitally important for an educated man to be able to argue both sides of an issue with equal skill and rhetorical ability. Their focus was on training elite Greeks to be successful – the Greek term for “virtue” was synonymous with “success.” Thus, the sophists were in the business of educating Greeks to be more successful, especially in the law courts and the public assemblies. They did not have a shared philosophical doctrine besides this idea that truth was relative and that the focus in life ought to be on individual achievement.

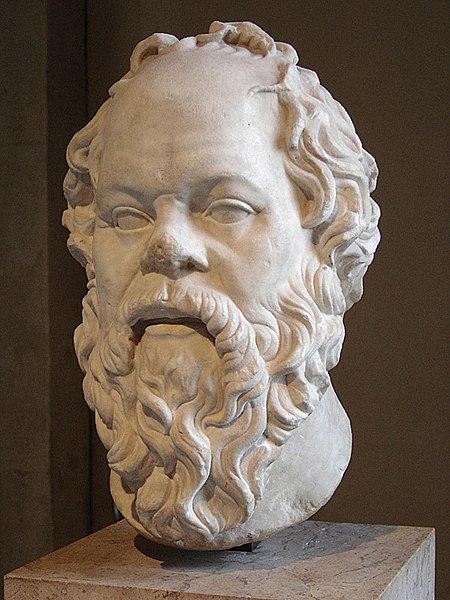

The men who became the most famous Greek philosophers of all time strongly disagreed with this view. These were a three-person line of teachers and students. Socrates (469 – 399 BCE) taught Plato (428 – 347 BCE), who taught Aristotle (384 – 322 BCE), who went on to be the personal tutor of Alexander the Great for a time. It is one of the most remarkable intellectual lineages in history – three of the greatest thinkers of Greek civilization and one of the greatest military and political leaders, all linked together as teachers and students.

Socrates never wrote anything down; like most of his contemporaries, he believed that writing destroyed the memory and undermined meaning, preferring spoken discourses and memorization. Instead, his beliefs and arguments were recorded by his student Plato, who committed them to prose despite sharing Socrates’ disdain for the written word. Socrates challenged the sophists and insisted that there are essential truths about morality and ethical conduct, but that to arrive at those truths one must be willing to relentlessly question oneself. He took issue with the fact that the sophists were largely unconcerned with ethical behavior, focusing entirely on worldly success; according to Socrates, there were higher truths and meanings to human conduct than mere wealth and political power.

Socrates used what later became known as the “Socratic Method” to seek out these fixed, unchanging rules of truth and ethics. In the Socratic Method, the teacher asks a series of questions of the student, forcing the student to examine her own biases and gaps in logic, until finally arriving at a more satisfying and reasonable belief than she started with. In Socrates’s case, his questions were meant to lead his interlocutors to arrive at real, stable truths about justice, truth, and virtuous politics. Unlike with the sophists’ mastery of rhetoric, the point of the question-and-answer sessions was not to prove that nothing was true, but instead to force one to arrive at truths through the most rigorous application of human reason.

A Roman copy of an original Greek bust of Socrates – as with many Greek sculptures, only the Roman copy survives. Most Greek statues were made of bronze, and over the centuries almost all were melted down for the metal.

Plato agreed with his teacher that there are essential truths, but he went further: because the senses can be deceived and because our insight is imperfect, only through the most serious contemplation and discussion can we arrive at truth. Truth could only be apprehended with the mind, not with the eye or ear, and it required rigorous discussion and contemplation. To Plato, ideas (which he called “Forms”) were more “real” than actual objects. The idea of a table, for instance, is fixed, permanent, and invulnerable, while “real” tables are fragile, flawed, and impermanent. Plato claimed that politics and ethics were like this as well, with the Form of Justice superseding “real” laws and courts, but existing in the intellectual realm as something philosophers ought to contemplate.

In Plato’s work The Republic he wrote of an imaginary polis in which political leaders were raised from childhood to become “philosopher-kings,” combining practical knowledge with a deep understanding of intellectual concepts. Plato believed that the education of a future leader was of paramount importance, perhaps even more important than that leader’s skill in leading armies. Of all his ideas, this concept of a philosopher-king was one of the most influential; various kings, emperors, and generals influenced by Greek philosophy would try to model their rule on Plato’s concepts right up to the modern era.

Plato founded a school, the Academy, in Athens, which remained in existence until the early Middle Ages as one of the greatest centers of thought in the world. Philosophers would travel from across the Greek world to learn and debate at the Academy, and it was a mark of tremendous intellectual prestige to study there. It prospered through the entire period of Classical Greece, the Hellenistic Age that followed, and the Roman Empire, only to be disbanded by the Byzantine (eastern Roman) emperor Justinian in the sixth century CE. It was, in short, both one of the most significant and one of the longest-lasting schools in history.

Plato’s most gifted student was Aristotle, who founded his own institution of learning, the Lyceum, after he was passed over to lead the Academy following Plato’s death. Aristotle broke sharply with his teacher over the essential doctrine of his teaching. Aristotle argued that the senses, while imperfect, are still reliable enough to provide genuine insights into the workings of the world, and furthermore that the duty of the philosopher was to try to understand the world in as great detail as possible. One of his major areas of focus was an analysis of the real-life politics of the polis; his conclusion was that humans are “political animals” and that it was possible to improve politics through human understanding and invention, not just contemplation.

Aristotle was the ancient world’s greatest intellectual overachiever. He single-handedly founded the disciplines of biology, literary criticism, political science, and logical philosophy. He wrote about everything from physics to astronomy and from mathematics to drama. His work was so influential that philosophers continued to believe in the essential validity of his findings well into the period of the Renaissance (thousands of years later) even though many of his scientific conclusions turned out to be factually inaccurate. Despite those inaccuracies, he unquestionably deserves to be remembered as one of the greatest thinkers of all time.

Art

The great legacy of Greek art is in its celebration of perfection and balance: the human body in its perfect state, perfect symmetry in buildings, and balance in geometric forms. One well known instance of this was in architecture, with the use of a mathematical concept known as the “golden ratio” (also known as the “golden mean”) which, when applied to building, creates forms that the Greeks, and many others afterwards, believed was inherently pleasing to the eye. The most prominent surviving piece of Greek architecture, the Parthenon of Athens dedicated to the polis’s patron goddess Athena, was built to embody the golden ratio in terms of its height and width. Likewise, in its use of symmetrical columns and beautiful carvings, it is widely believed to strike a perfect balance between elegance and grandeur.

Contemporary view of the Parthenon.

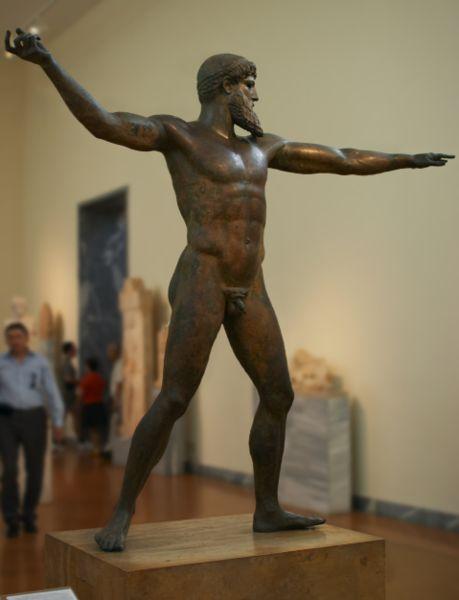

In turn, Greek sculpture is renowned for its unflinching commitment to perfection in the human form. The classical period saw a transition away from symbolic statuary, most of which was used in grave decorations in the Archaic period, toward lifelike depictions of real human beings. In turn, classical statues often celebrated the human potential for beauty, most prominently in nude sculptures of male warriors and athletes at the height of physical strength and development. Greek sculptors would often use several live models for their inspiration, combining the most attractive features of each subject to create the “perfected” version present in the finished sculpture – this was artistic humanism in its purest form.

One of the few original Greek bronze statues to survive, depicting either Zeus or Poseidon (Zeus would have held a lightning bolt, Poseidon a trident).

Most Greek art was destroyed over time, not least because the dominant medium for sculpture was bronze, which had allowed sculptors great flexibility in crafting their work. As Greece fell under the domination of other civilizations and empires in the centuries that followed, almost all of those bronzes were melted down for their metal. Fortunately, the Romans so appreciated Greek art that they frequently made marble copies of Greek originals. We thus have a fair number of examples of what Greek sculpture looked like, albeit in the form of the Roman facsimiles. Likewise, the Romans copied the Greek architectural style and, along with the Greek buildings like the Parthenon that did survive, we are still able to appreciate the Greek architectural aesthetic.

Exploration

Greek knowledge of the outside world was heavily based on hearsay; Greeks loved fantastical stories about lands beyond their immediate knowledge, and so even great historians like Herodotus reported that India was populated by magical beasts and by men with multiple heads. In turn, the immediate knowledge Greeks actually had of the world extended to the coasts of the Mediterranean, the Black Sea, Egypt, and Persia, since those were the areas they had colonized or were in contact with through trade. Through the Classical Age, a strong naval garrison was maintained by the Carthaginians, Phoenician naval rivals of the Greeks, at the straits of Gibraltar (the narrow gap between North Africa and southern Spain between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic Ocean), which prevented Greek sailors from reaching the Atlantic and thereby limiting their direct knowledge of the world beyond.

One exception to these limited horizons was a Greek explorer named Pytheas. A sailor from the small Greek polis Massalia that was well-known for producing ship captains and navigators, Pytheas undertook one of the most improbable voyages in ancient history, alongside the famous (albeit anonymous) Phoenician voyage around Africa earlier. Greek sailors already knew the world was round and had devised a system for determining latitude that was surprisingly accurate; Pytheas’ own calculation of the latitude of Massalia was only off by eight miles. Driven by a sense of how large the world must be, he set off to sail past the Carthaginian sentries and reach the ocean beyond.

Sometime around 330 BCE, roughly the same time Alexander the Great was heading off to conquer the Persian Empire, Pytheas evaded the Carthaginian blockade and sailed into Atlantic waters. He went on to sail up the coast of France, trading with and noting the cultures of the people he encountered. He then sailed across the English Channel, ultimately circumnavigating England and Scotland, then sailing east to (probably) Denmark, and ultimately returning home to Massalia. He subsequently wrote a book about his account titled On the Ocean that was met with scorn from most of its Greek audience since it did not have any fantastical creatures and mixed in genuine empirical observation (about distances and conditions along the way) with its narrative. Armchair critics claimed that it was impossible that he had gone as far as north as he said, because north of Greece it was quite cold enough and there was no way humans could live any farther north than that. Practically speaking, despite Pytheas’s voyage, the Greek world would remain defined by the shores of the Mediterranean.

Conclusion

“Classical Greece” is important historically because of what people thought as much as what they did. What the Greeks of the Classical Age deserve credit for is an intellectual culture that resulted in remarkable innovations: humanistic art, literature, and a new focus on the rational mind’s ability to learn about nature and to improve politics and social organization. What the Greeks had never done, however, was spread that culture and those beliefs to non-Greeks, both because of the Greek belief in their own superiority and their relative weakness in the face of great empires like Persia. That would change with the rise of a dynasty from the most northern part of Greece itself: Macedonia, and its king: Alexander.

Image Citations (Wikimedia Commons):

Peloponnesian War – Public Domain

Symposium – Marie-Lan Nguyen

Theater – Carole Raddato

Herodotus map – Bibi Saint-Pol

Socrates – Eric Gaba

Parthenon – Harrieta171

Statue – Usuario Barcex

Quote:

Demosthenes: Victor Bers, Demosthenes, Speeches 50–59, University of Texas Press (2003)

This chapter has been derived with minor modifications from Chapter 6 The Classical Age of Greece in Western Civilization: A Concise History.