Becoming a Citizen

- Pathways to Citizenship: Navigating the Process of Becoming a Citizen in America.

- Multicultural Roots: Tracing the History of Diversity in America from Indigenous Peoples to Present Day.

- Indigenous Legacies: Exploring the First American Tribes and Their Contributions to North America’s Multicultural Fabric.

- Multicultural North America: Recognizing the Diverse Societies That Existed Before European Colonization.

- Struggles for Citizenship: Immigrant Experiences in America’s Evolving Legal Landscape.

- Birthright Citizenship: Tracing the History and Significance of Citizenship by Birth in the United States.

- Gateways to America: Understanding Immigration Ports of Entry and Their Impact on Migration Patterns.

- Citizenship in Transition: Examining the Process of Naturalization in the Late 19th and Early 20th Centuries.

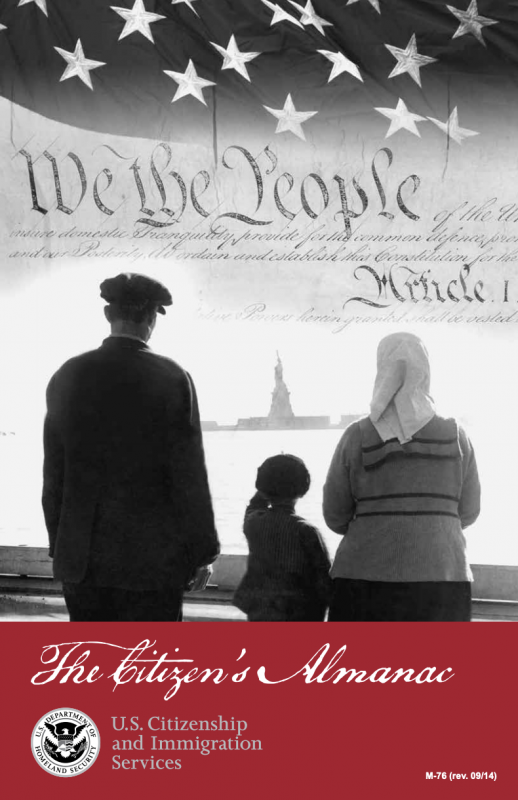

“The Citizen’s Almanac” by USCIS | Public Domain

“America is a nation peopled by the world, and we are all Americans,” wrote historian Ronald Takaki at the beginning of

A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America.[1]

His book brought together the multiple histories of citizenship, immigration, and America’s multicultural society while challenging a longstanding “master narrative of American history” that has marginalized the experiences of Indigenous people as well as those who came here (voluntarily and by force) from Africa, Asia, and Latin America (p. 5). For Takaki, it is important to view society through a different mirror that enables us to learn the how and why of America, its history, and our country’s “amazingly unique society of varied races, ethnicities, and religions” (p. 20).

Who then were the first citizens of America?

First American tribes lived in North America for 50,000 years before the arrival of Europeans. It is estimated that between 1492 and 1600, 90% of the native population died from diseases (smallpox, influenza, measles, chicken pox) introduced by European settlers.[2]

From the outset of European settlement, North America was a multiculturally diverse continent. Before the American Revolution, there were Spanish settlers in Florida, British in New England and Virginia, Dutch in New York, and Swedish in Delaware.

There were slaves – 10.7 million Africans brought to the New World – none of whom “immigrated” to this country under their own free will.[3] There were also indentured servants in the colonies as well as 50,000 convicts sent from jails in England.

The first Census in 1790 listed 3.9 million people living in the country – Native Americans were not counted. Nearly 20% of the people were of African heritage (but slaves were counted as three-fifths of a person).

At the time of the Civil War, the nation’s population was nearly 31.5 million people – 23 million in the northern states including 476,000 free Blacks and 9 million the southern states, of whom 3.5 million were enslaved Africans.[4] Follow the rest of the story at Immigration Timeline, a site from the Statue of Liberty/Ellis Island Foundation.

Throughout American history, immigrants from many different countries and faiths have struggled to obtain citizenship under the nation’s changing laws and policies. The United States, observed historian David Nasaw, “is and has always been both a nation of immigrants and a nation that periodically wages war against them”.[5]

Even “birthright citizenship,” the principle that anyone born in the country is automatically a citizen was initially just for “free white persons.” It has taken time, protests, and the Civil War to expand the boundaries of who could become an American citizen. Blacks were not granted citizenship until the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868. It took a Supreme Court decision, United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1895), to overthrow the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and establish birthright citizenship for Chinese Americans. American Indians did not gain full citizenship until 1924.

The modules for this standard explore the diverse histories of people becoming citizens of the United States, including the official rules and procedures for how someone becomes a United States citizen as well as less often discussed citizenship histories of indigenous peoples, Africans who came to America involuntarily as slaves, and immigrants who came here voluntarily. There is also a module focusing on the complicated story of Puerto Rican citizenship and a module exploring when someone should be granted asylum in the United States.

INVESTIGATE: Becoming a Citizen Through Immigration Gateways and Ports of Entry

Broadly defined, Citizenship consists of enjoying the benefits and assuming the responsibilities of membership in a shared community. Legally, the two most important tools traditionally used to determine citizenship are:

- Birthplace, or jus soli, being born in a territory over which the state maintains, has maintained, or wishes to extend its sovereignty.

- Bloodline, or jus sanguinis, citizenship as a result of the nationality of one parent or of other, more distant ancestors.[6]

All nations use birthplace and bloodlines in defining attribution of citizenship at birth. However, two other tools are used in citizenship law, attributing citizenship after birth through naturalization:

- Marital status, in that marriage to a citizen of another country can lead to the acquisition of the spouse’s citizenship.

- Residence, past, present, or future within the country’s past, present, future, or intended borders (including colonial borders)

Immigration Gateways, Ports of Entry, and Citizenship Histories

United States citizenship, however, is more than a set of legal principles that are applied in a court of law; citizenship is the product of historical developments and changing policies toward migrants and newcomers.

From colonial times, those who came here from other places entered the United States through one of the following Immigration Gateways or Ports of Entry, many of which were islands:

- Castle Island

- Ellis Island

- Sullivan’s Island

- Angel Island

- Pelican Island

- U.S./Mexico Border

The citizenship histories of diverse Americans can be accessed at the following resourcesforhistoryteachers wiki pages:

- African Americans: Slavery in Colonial North America; The Growth of Slavery after 1800; and Post Civil War African American Civil Rights

- European Americans: European Immigration Before the Civil War

- Chinese Americans: Chinese Immigration to the United States

- Mexican Americans: Mexican Immigration to the United States

- Native Americans: Native American Citizenship

- Muslim Americans: Muslim Immigration to the United States

Not everyone who entered the United States during the 19th and 20th centuries automatically became a citizen.[7] Following the passage of the Naturalization Act of 1906, immigrants had to file a petition for citizenship, be able to speak English, reside in the country for between 2 and 7 years, and have a hearing before a judge that usually involved answering questions orally about U.S. history and government (Background History of the United States Naturalization Process). Passing a spoken test became a formal requirement for citizenship in 1950.

- How did pre-colonial North America exhibit multiculturalism, and what were the characteristics of the diverse societies that existed before European arrival?

- How have immigrants navigated the evolving legal landscape of citizenship in America, and what are some common challenges and barriers they have faced throughout history?

- What is the historical significance of birthright citizenship in the United States, and how has its interpretation and application evolved over time?

- How do immigration ports of entry serve as gateways to America, and how have they influenced migration patterns and demographic changes throughout history?

- What were the processes and requirements for naturalization in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and how did they reflect the social and political context of the time?

& (2020). Building Democracy for All. EdTech Books. https://edtechbooks.org/democracy

Licensing

CC BY-NC-SA: This work is released under a CC BY-NC-SA license, which means that you are free to do with it as you please as long as you (1) properly attribute it, (2) do not use it for commercial gain, and (3) share any subsequent works under the same or a similar license.

CC BY-NC-SA: This work is released under a CC BY-NC-SA license, which means that you are free to do with it as you please as long as you (1) properly attribute it, (2) do not use it for commercial gain, and (3) share any subsequent works under the same or a similar license.

- Takaki, R. T. (2008). A different mirror: A history of multicultural America (First revised edition.). Back Bay Books/Little, Brown, and Company. https://cuny-jj.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01CUNY_JJ/20v1bi/alma990087566320106128 ↵

- Guns Germs & Steel: Variables. Smallpox | PBS. (n.d.). Retrieved December 7, 2022, from https://www.pbs.org/gunsgermssteel/variables/smallpox.html ↵

- Gates, Jr., H. L. (2013, January 2). How Many Slaves Landed in the U.S.? | The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross | PBS. The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross. https://www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/history/how-many-slaves-landed-in-the-us/ ↵

- NCpedia | NCpedia. (n.d.). Retrieved December 7, 2022, from https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/north-and-south-1861 ↵

- Nasaw, D. (2020, May 19). America’s Immigration Paradox. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/19/books/review/one-mighty-and-irresistible-tide-jia-lynn-yang-the-deportation-machine-adam-goodman.html ↵

- Hansen, R., & Weil, P. (2002). Dual Nationality, Social Rights and Federal Citizenship in the U.S. and Europe: The Reinvention of Citizenship. Berghahn Books. https://books.google.com/books?id=sHTJ2Zy4vXQC&pg=PA2&lpg=PA2&dq#v=onepage&q&f=false ↵

- Bein, J. (2016, November 2). Becoming a Citizen in the Late 19th and Early 20th Centuries. Museum at Eldridge Street. https://www.eldridgestreet.org/history/becoming-a-citizen-in-the-late-19th-and-early-20th-centuries/ ↵