You can say that but should you?

Do We Have a Right to Hate Speech? Concept and Constitutionality of Hate Speech in the U.S.

M. Victoria Pérez-Ríos

- Exploring Hate Speech: Concept and Constitutionality in the U.S.

- Broadest Protection: Freedom of Speech in the American Context.

- Schenck v. United States (1919): Setting Precedent on Speech Limitations.

- Defining Hate Speech: Understanding its Nature and Impact.

- Relevance of Hate Speech: Societal Implications and Legal Considerations.

- Hate Speech Today: Current Constitutional Doctrine in the U.S.

- Addressing Hate Speech: Recommendations to Mitigate its Harmful Effects in American Society.

INTRODUCTION

The United States (U.S.) is among the countries that provide the broadest protection of freedom of speech in the world, thanks to the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution which states that “Congress shall make no law … abridging freedom of speech,” and which has been interpreted by the Supreme Court of the U.S. (SCOTUS) for more than fifty years. According to the “Global Expression Report 2023,” the U.S., with a score of 87 points, occupies position no. 14 in the world on freedom of speech.[1] This position fluctuates because what constitutes constitutional free speech changes with the times.

The first case of freedom of speech SCOTUS decided was Schenk v. United States in 1919 and it had a restricted view of this right; freedom of speech expanded up to the 1950s when McCarthyism undermined it; and then freedom of speech expanded again starting with Brandenberg v. Ohio in 1969 (see Timeline). Currently, freedom of speech is under attack in the U.S. at the state and local levels and courts will have to decide, depending on lawsuits, whether this wide protection established in the past decades remains.[2]

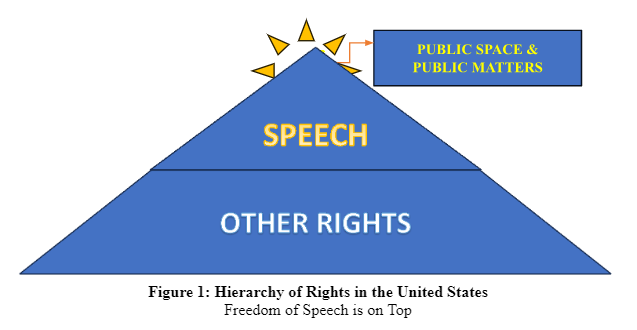

For SCOTUS, freedom of speech is essential to a democratic form of government; freedom of speech is necessary to defend all the other rights that “we the people” have. As a result, in a hierarchical pyramid of rights, the top position is reserved for freedom of speech (See: Below, Figure 1). Due to this “preferred” position, the burden of proof falls on the party that wants to limit that freedom of speech. Within speech, “speech at a public place on a matter of public concern, is entitled to ‘special protection’ under the First Amendment”.[3]

In the absence of a definition in our constitutional text, SCOTUS recognizes that freedom of speech goes beyond spoken and written words and envelopes non-verbal communication or speech plus (also known as symbolic speech). That is why when we use the phrase “freedom of speech,” we are really referring to freedom of expression. Examples of speech plus include gestures, artistic expressions, flags, and actions like wearing specific pieces of clothing and accessories, and the burning of objects to convey a message (See: Below, Figure 2).

In the absence of a definition in our constitutional text, SCOTUS recognizes that freedom of speech goes beyond spoken and written words and envelopes non-verbal communication or speech plus (also known as symbolic speech). That is why when we use the phrase “freedom of speech,” we are really referring to freedom of expression. Examples of speech plus include gestures, artistic expressions, flags, and actions like wearing specific pieces of clothing and accessories, and the burning of objects to convey a message (See: Below, Figure 2).

Furthermore, the Constitution of the U.S. recognizes any person’s right to exercise freedom of speech no matter who is offended. Does that mean that freedom of speech is limitless? The answer is no. First, the Constitution protects our freedom of speech from government (at the federal, state, and local levels) interference, not from the interference of private actors like individuals, businesses, and private organizations. For example, a private employer can ban proselytizing in favor of a specific political party on business premises without proving that it is interfering with work.

Second, the Supreme Court has recognized that under certain circumstances security, truth, and children’s welfare, among other values, trump speech. That is why freedom of speech is subject to (1) time, place, and manner limitations. And (2) content limitations. For example, sedition, threats, incitement, defamation, obscenity, and copyright infringement are unconstitutional and are called non-protected speech. What this article explores is the constitutionality of a specific speech content, that is, the one that can be identified as hate speech. Common law or constitutional state law limitations are beyond the scope of this article.[4]

HATE SPEECH: REAL-LIFE SCENARIO VIDEOS

Now, take a few minutes to watch these seven videos on hate speech, each based on real-life scenarios. Then, answer these questions for each video:

- Can we assume that the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) would find these actions constitutional?

- What precedents or arguments about free speech would they use to support their decision?

VIDEO 1:

VIDEO 2:

VIDEO 3

VIDEO 4

VIDEO 5

VIDEO 6

VIDEO 7

HATE SPEECH: CONCEPT AND RELEVANCE

What is Hate Speech?

Hate conveys an image of hurting others. However, not all speech that hurts others is hate speech. That is why, expressing the truth is not hate speech. For example, speech about white privilege may be hurtful to some people but it is not what is considered hate speech.[5] There is no definition of hate or hateful speech in the U.S. but its concept coincides, to some degree, with the traditional “fighting words” that SCOTUS used to decide Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire (1942).

the insulting or “fighting” words — those which, by their very utterance, inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace. It has been well observed that such utterances are no essential part of any exposition of ideas, and are of such slight social value as a step to truth that any benefit that may be derived from them is clearly outweighed by the social interest in order and morality.[6]

Based on the seven videos you have just watched, what did the speech used in all of them have in common besides being offensive? Is the target of the speech similar in all these real-life scenarios? Yes, you are right, all these cases are similar because they show offensive speech, half-truths, and lies used against minorities based on gender/sex, race, ethnicity, religion, ideology, and sexual orientation. In sum, hate speech disregards the truth and attacks vulnerable individuals and groups.

To elaborate the concept of hate speech further, the working definition of the United Nations (UN) is both useful—the U.S. has no definition—and relevant—the U.S. is a party, since 1992, to the legally binding 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) addressing freedom of expression in Articles 19 and 20. The 2019 “United Nations Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech” defines hate speech as “any kind of communication in speech, writing or behavior, that attacks or uses pejorative or discriminatory language with reference to a person or a group on the basis of who they are; in other words, based on their religion, ethnicity, nationality, race, color, descent, gender or other identity factor.”[7]

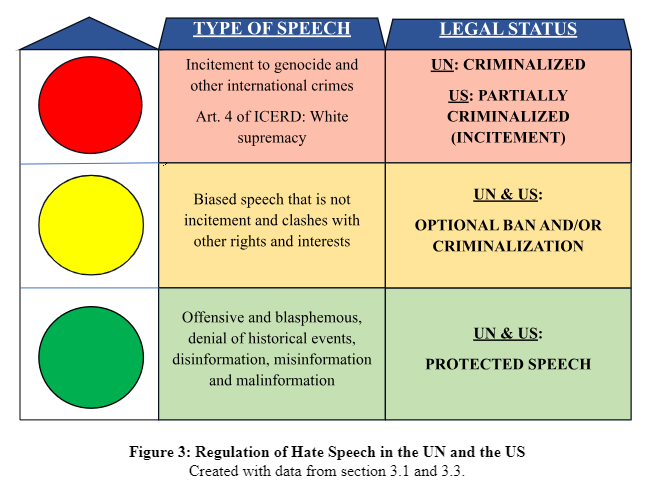

Thus, hate speech includes speech plus and is unconcerned with the truth because it “attacks or uses pejorative or discriminatory language” based on inherent characteristics of “a person or group.” Moreover, the UN categorizes hate speech into three groups, depending on its severity. The first and most severe group is incitement to genocide and other violations of international law, and it must be criminalized. The second, intermediate category includes “biased speech” below incitement; it may be criminalized to protect other rights. The least severe group is “offensive and blasphemous speech, denial of historical events, disinformation, misinformation and malinformation” and should always be protected.[8] The information below shows that U.S. constitutional doctrine protects some types of speech the UN includes in categories 1 and 2.

Why is Hate Speech Relevant?

Agreement on the benefits that a wide protection of freedom of speech provides to a democratic system does not equate to dismissing the varied and far-reaching negative effects of hate speech. Consequently, it is relevant to examine hate speech to understand how to limit the loss and suffering it causes. According to studies in the fields of psychology, neurobiology,[9] and international law (UN, Video) exposure to hate speech (1) affects the mental health of individuals; (2) undermines the wellbeing of individuals, groups and society at large; and (3) is a precursor to different types of crimes including discrimination, assault, murder,[10] and genocide.

In our society, the internet is widely used to spread hate. Moreover, the internet amplifies the influence of hate speech because it is accessible 24/7; users do not have to confront dissent or alternative views; anonymity is pervasive; and the absence of immediate, visible consequences, including riots, makes it difficult to prosecute it. As a result, the following information focuses on online activity. The findings of a study of “a dataset of 6 million Reddit comments shared in 174 college communities” are especially relevant in the context of John Jay College of Criminal Justice because it shows the impact on individual mental health and general well-being of college students, including the following:

heightened stress, anxiety, depression, and desensitization. Victimization, direct or indirect, has also been associated with increased rates of alcohol and drug use—behaviors often considered risky in the formative college years. Further, hateful speech exposure has negative effects on students’ academic lives and performance, with lowered self-esteem, and poorer task quality and goal clarity-disrupting the very educational and vocational foundations that underscore the college experience.[11]

This same study mentions the impact on the overall well-being of the college community too. Among the different inquiries into the relationship between online hate speech and hate crimes, a 2019 study of 100 U.S. cities found a correlation (not causation) between online hate speech and hate crimes against minorities based on race, ethnicity, and national origin.[12] Another found a correlation too between candidate to the presidency Donald Trump’s Anti-Muslim tweets and hate crimes against this minority group.

Our findings are consistent with a role for social media in the normalization of anti-minority sentiments. In line with this hypothesis, we find that Trump’s tweets about Muslims are highly correlated with the number of anti-Muslim hate crimes, but only for the time period after the start of his presidential campaign. … This is at least suggestive of the idea that social media, and Trump’s tweets in particular, may contribute to a climate that reduces the social sanctions against and increases the incidence of hate crimes.[13]

And the field of international law recognizes hate speech as a precursor to genocide (UN, Video). For example, approximately nine months of anti-Tutsi hate speech broadcast by RTML (Radio Television Libre des Mille Collines or Free Radio and Television of the Thousand Hills) preceded the April – July 1994 Rwandan genocide.[14] As early as 8 July 1993 transcripts from RTML show dehumanizing insults—Tutsis become “les Inyenzi” or “the cockroaches”—and misinformation—“there is no difference between the FPR [in English the RPF or Rwandan Patriotic Front] and the cockroaches.”[15]

HATE SPEECH: CURRENT CONSTITUTIONAL DOCTRINE

In Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire (1942), SCOTUS defended a more restricted view of freedom of speech than the one characterizing our times. As a result, insulting a police officer—’You are a God damned racketeer’ and ‘a damned Fascist’—and the government—’the whole government of Rochester are Fascists or agents of Fascists’—constituted “fighting words,” and thus, non-protected speech.[16] Current constitutional doctrine recognizes a very broad freedom of speech that protects the right to offend others as shown in the following paragraph from Matal v. Tam, 2017, p. 582 U.S. 243 that confirmed the Circuit Court decision affirming the right of the leader of all Asian-American rock band to copyright “The Slants” as their artistic name.

The Government has an interest in preventing speech expressing ideas that offend. And, as we have explained, that idea strikes at the heart of the First Amendment. Speech that demeans on the basis of race, ethnicity, gender, religion, age, disability, or any other similar ground is hateful; but the proudest boast of our free speech jurisprudence is that we protect the freedom to ‘the thought that we hate.’ United States v. Schwimmer,279 U.S. 644, 655, 49 S.Ct. 448, 73 L.Ed. 889 (1929) (Holmes, J., dissenting). [Emphasis added].

The only exceptions to this wide protection include cases in which hate speech becomes incitement to commit a crime. Per curiam (meaning the agreement of all nine justices), SCOTUS held in Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) the unconstitutionality of incitement. For speech to be considered incitement, it must be (1) ‘directed at inciting or producing imminent lawless action’ and (2) ‘likely to incite or produce such action.’[17] It could be said that SCOTUS canceled in Brandenburg its “fighting words” doctrine because all the justices found that the Klan members’ anti-Black, anti-Jewish and ‘revengeance’ [sic] speech preserved in two films was constitutional.[18]

Approximately a decade before Brandenburg, the five-four opinion of SCOTUS in Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U.S. 1 (1949) provided broad protection to what we call hate speech today. Justice Douglas stated the following:

A function of free speech under our system of government is to invite dispute. It may indeed best serve its high purpose when it induces a condition of unrest, creates dissatisfaction with conditions as they are, or even stirs people to anger. Speech is often provocative and challenging. It may strike at prejudices and preconceptions and have profound unsettling effects as it presses for acceptance of an idea. That is why freedom of speech, though not absolute . . . is nevertheless protected against censorship or punishment, unless shown likely to produce a clear and present danger of a serious substantive evil that rises far above public inconvenience, annoyance, or unrest.[19] [Emphasis added].

According to Terminiello, for speech to become incitement, it must be “likely to produce a clear and present danger of a serious substantive evil that rises far above public inconvenience, annoyance, or unrest.” Brandenburg clarified that incitement was proven with a two-prong test focusing on intent and probability of undermining the peace.[20]

The previous cases focus on the written or spoken word except for Brandenburg already demonstrated that SCOTUS saw symbolic hate speech as protected by the First Amendment to the Constitution because, in addition to the disparaging words, the members of the KKK were filmed in full regalia, carrying weapons and next to a burning cross. However, it is more recently that SCOTUS has decided cases where symbolic hate speech was the crux of the case, including the following, and it has reaffirmed that symbolic hate speech is protected speech:

(1) Marching with Nazi uniforms, including armbands with swastikas, in a locality where the majority is Jewish, including Holocaust survivors. Per curiam it reversed the denial, by the Supreme Court of Illinois, of an injunction to march by affirming that “The State must allow a stay where procedural safeguards, including immediate appellate review, are not provided”.[21]

(2) Burning crosses in public areas or in other people’s private property unless the intent of this action is to intimidate. Basically, SCOTUS recognizes that cross-burning can be just the expression of a political idea. As a result, Justice O’Connor, joined by Chief Justice Rehnquist, Justice Breyer, and Justice Stevens, affirms “The act of burning a cross may mean that a person is engaging in constitutionally proscribable intimidation, or it may mean only that the person is engaged in core political speech.”[22]

(3) Picketing funerals of the military with signs stating “‘God Hates the USA/Thank God for 9/11,’ ‘America is Doomed,” ‘Don’t Pray for the USA,’ ‘Thank God for IEDs,’ ‘Thank God for Dead Soldiers,’ ‘Pope in Hell,’ ‘Rape Boys,’ ‘God Hates Fags, ’ ‘You’re Going to Hell,’ and ‘God Hates You.’”[23] Data provided in this decision shows that The Westboro Baptist Church had picketed more than 600 funerals by 2011 but always respected time, place, and manner regulations.

This wide protection afforded to hate speech clashes with U.S. obligations at the international level (For a summary, see: Below, Figure 3). For many, it is irrelevant because for them the interference of international law is illegitimate. However, international law is part of our legal system; Article VI (2) of the Constitution includes international treaties ratified by the U.S. as the Supreme Law of the Land. For international treaties to have legal effects in the U.S., our government must incorporate them via federal law because the U.S. is a dualist country regarding the domestic effects of international law.

As explained above in What is Hate Speech?, the ICCPR is applicable in the U.S. Regarding hate speech, the ICCPR recognizes “certain restrictions [to freedom of expression] … as are provided by law and are necessary” (Article 19 (3)) that in principle is compatible with the U.S. position regarding hate speech. That is, the U.S. has the right to consider sedition, threats, incitement, defamation, obscenity, and copyright infringement as non-protected speech in the U.S.. However, the ICCPR bans some types of hate speech that SCOTUS finds constitutional or “[a]ny advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence” (Article 20 (2)) (OHCHR).[24]

In addition, since 1994 the U.S. has been a party to the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination or ICERD that advances proscribing White Supremacy speech in Article 4. Article 4 imposes these duties,

(a) Shall declare an offense punishable by law all dissemination of ideas based on racial superiority or hatred, incitement to racial discrimination, as well as all acts of violence or incitement to such acts against any race or group of persons of another color or ethnic origin, and also the provision of any assistance to racist activities, including the financing thereof;

(b) Shall declare illegal and prohibit organizations, and also organized and all other propaganda activities, which promote and incite racial discrimination, and shall recognize participation in such organizations or activities as an offense punishable by law;

(c) Shall not permit public authorities or public institutions, national or local, to promote or incite racial discrimination.

However, the government of the U.S. uses its wide constitutional protection of speech to shield itself from complying with Article 4.

The U.S. RUD [Reservations, Understandings and Declarations to ICERD] stating it does not accept any obligation under Article 4 to restrict freedom of speech plainly confirms which side of the balance the United States values more. Protecting speech—namely hate speech—is more sacred to the United States than abolishing the evils of racism. This does not reflect a sincere commitment to uphold ICERD’s primary purpose of eliminating racial discrimination.[25]

Although there is a similar obligation regarding sexist and misogynist messages in Article 5 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), it is not applicable to the U.S. because we are not a party to it.

CONCLUSIONS: RECOMMENDATIONS TO NEUTRALIZE HATE SPEECH IN THE U.S.

Based on the information presented here, hate speech in the U.S. is protected speech unless it constitutes incitement to commit a crime or accompanies an actual punishable offense. For example, assault, robbery, aggravated harassment, criminal mischief, and property crimes (graffiti too)[26]. Furthermore, although incitement is a crime, the threshold to prove incitement is high. Considering that with the widespread use of the internet, reactions to hate speech will usually adopt the form of more hate speech and not immediate unrest; it may be time for SCOTUS to look at hate speech from the perspective of medium and long-term effects.

Distinguishing hate speech from incitement is complicated. For that reason, the UN has developed the six-step Rabat Threshold Test that examines the “(1) … context, (2) status of the speaker, (3) intent to incite the audience against a target group, (4) content and form of the speech, (5) extent of its dissemination and (6) likelihood of harm, including imminence”;[27] this is a high threshold too.

From the perspective of international human rights law and constitutional law, it is positive to establish a high threshold to prove incitement to avoid punishing hate speech just because the government or the audience finds it offensive. However, the broad protection of hate speech in the U.S. places our country at odds with international law regarding the most severe category of hate speech. That is, except for incitement to genocide, the U.S. does not punish in any way Art. 4 of ICERD.[28] I do not mention hate speech directed at women or people with disabilities because the U.S. is not a party to the treaties protecting them. In addition, the LGBTQ+ community, indigenous groups, and aged persons do not have their own legally binding international treaties.

Does this mean that there is nothing to be done? For the reasons explained above in HATE SPEECH: CONCEPT AND RELEVANCE, it is important to find ways of neutralizing the negative effects of hate speech within a democratic society. Inspired by the civil rights movement and human rights law, I propose two relevant solutions — raising awareness and contacting public officers— in which you, as students, can participate now.

First, spread awareness of the negative repercussions of exposure to hate speech to all involved, not only the victims but to society. For example, establish an awareness campaign around June 18 or the International Day to counter Hate Speech. Students could organize panel discussions with experts, roundtables in which students will share their stories, and distribute flyers with relevant information.

Second, contact public officers. According to the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, we have the right to petition the government. Change may be difficult to effect at the federal level because of its divided Congress where no agreement on an anti-hate speech will be reached. That is why the state and local government should be the target of those anti-hate speech petitions. States have reserved powers vis-à-vis the federal government, including security, morality, and education.[29][30] First, find out who is your representative at the local, state, and federal levels and email them with your concerns and proposals. In addition, John Jay, and the whole CUNY, have codes of conduct and administrators can be contacted too.

Review Questions

1. How does the concept of hate speech intersect with the constitutional principles of free speech in the United States, and what are the key legal precedents shaping its interpretation?

2. What factors contribute to the U.S. having the broadest protection of freedom of speech compared to other countries, and how does this impact the regulation of hate speech?

3. How did the Supreme Court’s decision in Schenck v. United States establish a framework for limiting speech rights in certain circumstances, and what are the implications for hate speech regulation?

4. What are the various definitions and criteria used to define hate speech, and how do scholars and policymakers understand its nature and societal impact?

5. Why is hate speech considered relevant in contemporary society, and what are the social, political, and legal implications of its proliferation?

6. How does current constitutional doctrine in the U.S. address hate speech, and what factors influence the courts’ interpretation and application of free speech rights in hate speech cases?

7. What are some recommendations or strategies proposed to address hate speech and its harmful effects in American society, and how might these approaches balance free speech protections with the need to combat discrimination and intolerance?

About the author: M. Victoria Pérez-Ríos, PhD, JD teaches international human rights and comparative criminal justice systems as a Substitute Assistant Professor at the Political Science Department and the International Crime and Justice MA Program of John Jay College, and taught American government at LaGuardia CC.

- International IDEA (Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance). (Circa 2023). Global state of democracy indices, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2024, from https://www.idea.int/democracytracker/gsod-indices. ↵

- Boon, R. (2023, March 15). Experts say attacks on free speech are rising across the U.S. PBS NewsHour. Retrieved February 17, 2024, from https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/experts-say-attacks-on-free-speech-are-rising-across-the-us ↵

- Snyder v. Phelps. (n.d.). Oyez. Retrieved May 22, 2024, from https://www.oyez.org/cases/2010/09-751 ↵

- Lakier, G. (2021, May). The non–first amendment law of freedom of speech. Harvard Law Review 134 (7): 2299-2381. Retrieved February 22, 2024, from https://harvardlawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/134-Harv.-L.-Rev.-2299.pdf. ↵

- Fulwood III, S. (2014, May 6). The Conundrum of White-Male Privilege. The Center for American Progress. Retrieved February 19, 2024, from https://www.americanprogress.org/article/the-conundrum-of-white-male-privilege/ ↵

- Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U.S. 568 (1942). Oyez. Retrieved February 25, 2024, from https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/315/568/ ↵

- United Nations. (May 2019). UN strategy and plan of action on hate speech. Retrieved February 18, 2024, from https://www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/documents/advising-and-mobilizing/Action_plan_on_hate_speech_EN.pdf. ↵

- The UN Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect. (September 2020). Detailed guidance on implementation for United Nations field presences. Retrieved February 23, 2024, from https://www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/documents/UN%20Strategy%20and%20PoA%20on%20Hate%20Speech_Guidance%20on%20Addressing%20in%20field.pdf ↵

- Pluta, A; Mazurek, J; Wojciechowski, J; Wolak, T, Soral, W. & Bilewicz, M. (2023, March 13). Exposure to hate speech deteriorates neurocognitive mechanisms of the ability to understand others' pain. Scientific Reports 13 (1): 4127. Retrieved February 19, 2024, from doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-31146-1. PMID: 36914701; PMCID: PMC10011534 ↵

- Lavietes, M. (2023, August 23). Killing over the Pride flag follows far right’s years of criticism of the LGBTQ symbol: Far-right online personalities have repeatedly linked the flag to the decades-old trope that LGBTQ people are ‘grooming’ or sexualizing children in recent years. NBC News. Retrieved February 29, 2024, from https://www.nbcnews.com/nbc-out/out-news/killing-pride-flag-follows-far-rights-years-criticism-lgbtq-symbol-rcna101478 ↵

- Saha, K; Chandrasekharan, E. & De Choudhury, M. (2019). Prevalence and Psychological Effects of hateful speech in online college communities. Proceedings of the ACM Web Science Conference, 2019, 255–264. Retrieved February 24, 2024, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7500692/pdf/nihms-1625892.pdf ↵

- Relia, K; Li, Zhengyi; Cook, S. H; & Chunarag, R. (2019). Race, ethnicity, and national origin-based discrimination in social media and hate crimes across 100 U.S. cities. Thirteenth International AAAI [Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence] Conference on Web and Social Media Vol. 13, Retrieved February 24, 2024, from https://arxiv.org/pdf/1902.00119.pdf ↵

- Müller, K & Shwarz, C. (2020, July 24). From hashtag to hate crime: Twitter and anti-minority sentiment. Retrieved February 25, 2024, from https://ssrn.com/abstract=3149103 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3149103 or https://www.qmul.ac.uk/sef/media/econ/events/Hashtag_to_Hatecrime_small.pdf ↵

- n.a. (2011, May 17). Rwanda: How the genocide happened. BBC.com. Retrieved February 24, 2024, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-13431486 ↵

- Concordia University. (1993, July 8). RTML Transcripts: p. 2. Montreal Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies. Retrieved February 24, 2024, from http://migs.concordia.ca/links/documents/RTLM_08Jul93_fr_tape0051.pdf ↵

- Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U.S. 568 (1942). Oyez. Retrieved February 25, 2024, from https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/315/568/ ↵

- Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969). Oyez. Retrieved February 11, 2024, from https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/395/444/ ↵

- Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969). Oyez. Retrieved February 11, 2024, from https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/395/444/ ↵

- Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U.S. 1 (1949). Retrieved February 25, 2024, from https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/337/1/#tab-opinion-1939623 ↵

- Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969). Oyez. Retrieved February 11, 2024, from https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/395/444/ ↵

- National Socialist Party of America v. Village of Skokie, 432 U.S. 43 (1977). Oyez. Retrieved February 28, 2024, from https://www.oyez.org/cases/1976/76-1786 ↵

- Virginia v. Black. (n.d.). Oyez. Retrieved February 5, 2023, from https://www.oyez.org/cases/2002/01-1107 ↵

- Snyder v. Phelps. (n.d.). Oyez. Retrieved May 22, 2024, from https://www.oyez.org/cases/2010/09-751 ↵

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) (2020, April 20). One-pager on incitement to ‘hatred.’ Retrieved February 23, 2024, from https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Rabat_threshold_test.pdf ↵

- Watson, M. K. (2020, January 6). The United States' hollow commitment to eradicating global racial discrimination. American Bar Association: Human Rights. Retrieved February 26, 2024, from https://www.americanbar.org/groups/crsj/publications/human_rights_magazine_home/black-to-the-future-part-ii/the-united-states--hollow-commitment-to-eradicating-global-racia/ ↵

- NYC Office for the Prevention of Hate Crimes. (n.d.). What is a Hate Crime? Retrieved on June 10, 2024, from https://www.nyc.gov/assets/stophate/downloads/pdf/OPHC-WhatIsAHateCrime.pdf ↵

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) (2020, April 20). One-pager on incitement to ‘hatred.’ Retrieved February 23, 2024, from https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Rabat_threshold_test.pdf ↵

- Ghanea, Nazila. (2012, August 28). The concept of racist hate speech and its evolution over time. Paper presented at the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination’s Day of thematic discussion on Racist Hate Speech. Geneva. 81st session. Retrieved February 26, 2024, from https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/HRBodies/CERD/Discussions/Racisthatespeech/NazilaGhanea.pdf ↵

- Constitutional amendments – amendment 10 – “powers to the states or to the people.” (n.d.). Ronald Reagan. Retrieved May 24, 2024, from https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/constitutional-amendments-amendment-10-powers-states-or-people ↵

- Lakier, G. (2021, May). The non–first amendment law of freedom of speech. Harvard Law Review 134 (7): 2299-2381. Retrieved February 22, 2024, from https://harvardlawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/134-Harv.-L.-Rev.-2299.pdf ↵