On the Inherent Ambiguity of Freedom of Speech in a Democratic Republic

Jonathan Berk

Issues/Topics Covered in this Chapter

- The inherent tension between the right to free speech and the responsibilities that come with it, including considerations of harm to individuals or societal stability.

- A democracy emphasizes the direct involvement of citizens in decision-making, whereas a republic relies on elected representatives to govern on behalf of the people.

- The landmark U.S. Supreme Court case, Schenck v. United States, established the ‘clear and present danger’ test, significantly impacting the interpretation of free speech under the First Amendment.

Democracy means rule by the people. A democratic procedure is, most abstractly, one in which the group members have some sort of say in the decisions that the group makes as a collective. The specific way in which people contribute to making these decisions certainly varies and depends on the size and scope of the group. It could mean that a group of friends all deliberate together over where they are going to have dinner that evening. It could also mean that an entire population of people vote for candidates for political office who will then be given political power to rule over those same individuals. In either case, the people who are part of a group are contributing to the decisions enacted by the group itself.

Let’s take the former case (a group of friends deciding on where to have dinner) and imagine it expanded steadily to the magnitude of the latter case (a state). It immediately becomes clear that uniform agreement will not be achievable. Even a relatively large group of friends will face difficulty agreeing on dinner plans and some of them will be disappointed by the group’s collective decision. This is not quite a political concern, however, since those disappointed friends are free to eat elsewhere and make their own decisions based on their appetites rather than the group’s collective decision. But this seems to be where the analogy between the two groups making democratic decisions (friends deciding where to eat and a population deciding its laws) comes to an end; as members of a state, we are not free to sever our ties from the state in those instances where the decisions, in this case, laws, conflict with our individual wants or even needs. Or, rather, perhaps we are free to do so, but this becomes rebellion. By severing our ties with the state, we severe them completely. This was, in fact, what the Declaration of Independence set out to justify to the world in its explanation for the legitimacy of its act of rebellion against Britain.

But this calls for some explanation. Why would an act of rebellion require justification? To whom is this justification directed? The Declaration of Independence states that the need to justify an act of rebellion comes from “a decent respect to the opinions of mankind.”[1] However, it does not specify whose opinions or who needs to hear the justification. It seems that the act of rebellion severs the connections that would require one group to justify itself to another or feel compelled to explain their rebellion.

In other words, if one person or group rebels from another, it would no longer feel compelled to justify its reasons for doing so if its only motivation to offer justifications in the first place was severed by the rebellion. To whom was this attempt at legitimation directed? Certainly not to the British, to whom no justification beyond the act of rebellion itself was required.

Above state and political power, we can speculate a divine power holds sway. But it is not to a god-like power that the Declaration of Independence attempts to explain the legitimacy of its rebellion. God is mentioned in the Declaration of Independence only indirectly and austerely as “Nature’s God” responsible for the “separate and equal Station” among humans outside of the established rule of governments. Shortly after, God is mentioned again as responsible for endowing individuals with “certain unalienable Rights” and that it is the sole purpose of government “to secure these rights.” Therefore, it is immediately concluded that the justified use of power on behalf of the state derives exclusively “from the consent of the governed.” The Declaration of Independence acknowledges the importance of God as the creator of individuals with inalienable rights. However, it does not appeal to this particular concept of God to justify the act of rebellion that it legitimizes. The Declaration is a paradigmatically modern political text where God has significant metaphysical and epistemological importance but exerts minimal political or practical influence. In other words, the Declaration of Independence does not ask God for permission to rebel against the British, but instead dignifies the individual by imbuing them with inalterable rights – something that surely no human or historical force could muster. The creation of individuals with inherent rights requires some form of acknowledgment of a higher purpose beyond the everyday matters of the state and society. The question from the beginning of this paragraph still remains unanswered – to whom is the Declaration of Independence justifying itself?

Keeping in mind that the dignity of the individual as the possessor of permanent rights was the touchstone for the justification of rebellion, it only makes sense that it is in this same idea of an individual that legitimacy is sought. That is, it is to the people that the Declaration of Independence seeks to explain its right to rebellion. Keeping at bay the structural and systemic complications and even injustices inherent in addressing all the people in one fell swoop (let alone to do so in a society practicing slavery and built off of patriarchy), let us stick with this line of thinking in order to pull out a problem that is distinct but perhaps not unrelated to systemic injustice. If the people are the source of legitimacy for the explanation of the justification for rebellion, it seems logical that the new state set up in its place would seek its source of authority in the same idea of the individual. If the dignity of the individual is the source of political authority for the state, ought these same individuals not have a say in the determination of the actions of the state? If this connection doesn’t seem too far-fetched, democracy seems to stem from the very idea of a republic. It would thus seem that democracy fits nicely as the form of government that would derive from a foundational act of legitimacy that sees it necessary even to legitimize itself according to reasons (as opposed to, for instance, deriving legitimacy from lineage, revelation, or victory in combat). Democracy, as a form of government, seems to cohere and fit well with the idea of a legitimate state, that is, a republic. I will go on to argue that this seemingly nice fit between democracy and a republic is actually deeply problematic.

The word “republic” has origins distinct from “democracy”, and while not explicitly mentioning the people it certainly has its chief task directed toward them. “Republic” comes from “res publica”, or, the public being. Latin rather than Greek in origin, the word “republic” calls upon a different distinction than that of democracy. Democracy is opposed to monarchy, where the power is not exercised by the people but upon them, understood as subjects of the king. The legitimacy of the king’s rule over the people is supposed to be secured from an entirely distinct realm: lineage of nobility and religious warrant. Distinct from the idea of democracy, the idea of a republic is opposed to a tyranny of any form, where the purpose of the state is no longer to rule the people well but to harness them for the gain of those in power. (That the republic – both in ancient Rome as well as in Star Wars – is fated to become a tyranny seems to be the perennial tragedy of political life and stands in stark opposition to the more modern hope for a perpetually peaceful organization of radically different, because free, people. But I digress.) While certainly idealistic and quite removed from the actual historical processes that brought these terms to popular usage, their linguistic origins offer the opportunity for an insight into an important philosophical distinction. Both democracy and republic refer to the people but in importantly different ways. Democracy is a form of government principally concerned with who has a say in the collective decisions of the state; a republic, on the other hand, is an idea of the fundamental purpose of a state and its claim to legitimacy as such. That the two concepts, democracy and the republic, are inherently linked is not as obvious as one might think based on the previous discussion. In fact, it is not their coherence but their conflict that should interest us.

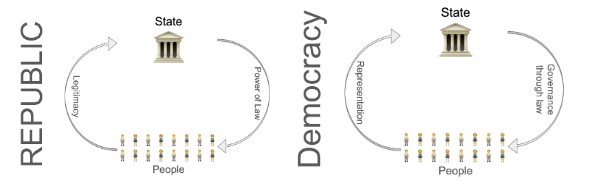

The task of a republic is to exercise collective power legitimately, that is, to rule its people according to what is right as opposed to what benefits those individuals who hold power. The task of democracy is to ensure that individuals have a say in the collective decision-making process at the seat of power. The former is a form of rulership, of governance, and the latter is a form of decision-making, of politics. Going back to the origins of the word “republic”, the creation of “a public thing” is in opposition to the individual domains of privacy. The public thing, the republic, is formed out of and against the private realm of our individual and familial lives. In modern societies, this distinction is evident in the contrast between the political and the economic, government and finance, democracy and capitalism. But the root of the private sphere, of the private sector, is the individual and familial bonds along with the necessary means to preserve them. (The term “economy” after all comes from “management of the home” – which is why home economics is redundant.) As a result, a fundamental difference appears in how democracy and a republic refer to people. A democracy considers individuals as potential decision-makers in a collective and immensely complex process of forming unity out of diversity; a republic considers individuals as belonging to a private sphere of their individual freedom and familial obligations, outside of which the state has its power and for the security of which the state ought to direct its power. When it comes to freedom of speech, this difference will take shape as a tension, if not an outright antagonism. That a democratic republic permits freedom of speech should seem both necessary (if it is to be a democracy at all) and impossible (if it is to be an effective republic that maintains the integrity of the public sphere and security of the private sphere).

The task of a republic is to exercise collective power legitimately, that is, to rule its people according to what is right as opposed to what benefits those individuals who hold power. The task of democracy is to ensure that individuals have a say in the collective decision-making process at the seat of power. The former is a form of rulership, of governance, and the latter is a form of decision-making, of politics. Going back to the origins of the word “republic”, the creation of “a public thing” is in opposition to the individual domains of privacy. The public thing, the republic, is formed out of and against the private realm of our individual and familial lives. In modern societies, this distinction is evident in the contrast between the political and the economic, government and finance, democracy and capitalism. But the root of the private sphere, of the private sector, is the individual and familial bonds along with the necessary means to preserve them. (The term “economy” after all comes from “management of the home” – which is why home economics is redundant.) As a result, a fundamental difference appears in how democracy and a republic refer to people. A democracy considers individuals as potential decision-makers in a collective and immensely complex process of forming unity out of diversity; a republic considers individuals as belonging to a private sphere of their individual freedom and familial obligations, outside of which the state has its power and for the security of which the state ought to direct its power. When it comes to freedom of speech, this difference will take shape as a tension, if not an outright antagonism. That a democratic republic permits freedom of speech should seem both necessary (if it is to be a democracy at all) and impossible (if it is to be an effective republic that maintains the integrity of the public sphere and security of the private sphere).

The Bill of Rights is the first set of amendments to the Constitution. These words are well chosen to express what they are: the Constitution literally constitutes, sets into motion, or establishes the power of the government and delineates its responsibilities; the Amendments literally amend, change, or limit the power of the government. And this is precisely what a Right is within the Bill of Rights – a limitation of the extent and scope belonging to the exercise of power that the government yields. From the perspective of governance, or a Republic, why would one ever imagine limiting or hindering the effective execution of the power of the governing body? History offers us a concrete answer: the unchecked power of the monarchical system of government displayed all too clearly that absolute power cannot be trusted, so in establishing the US government within the historical context criticizing monarchies it behooves the framers of the Constitution to address this problem from the start. But there is also a philosophical answer to the question: why limit the government’s power? Unlimited power leaves no room for the freedom of individuals from whom this power derives its legitimacy and for whom this power is supposed to govern. So the Bill of Rights and amendments to the Constitution in general ought not be thought of as an afterthought to the Constitution but as an integral aspect of it. The First Amendment serves as a perfect example of this because it limits the power of the government to preserve the necessary freedom for active members of a democracy. The text of the First Amendment reads as follows:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people to peaceably assemble, and to petition the Government from redress of grievances.[2]

While we are specifically concerned with the second clause (concerning the freedom of speech) it is illustrative to evaluate briefly the third. It is the right of the people to assemble, specifically to criticize the government. But the word “peaceably” is added. The addition of this qualifier suggests the same conflict between democracy and a republic discussed above. On the one hand, for this state to be a democracy, the people must be permitted to come together to voice their opinions about the very laws and governing practices they are subjected to; but doing so poses an inherent threat to the efficacy of those laws and governing practices. The right to assemble publicly in a unified criticism of the government challenges the power of the republic. So by adding the qualification that such assembly must be peaceful, we can interpret a suspicion of fear that such public assembly harbors the potential to disrupt the peace that the government is supposed to be responsible for.

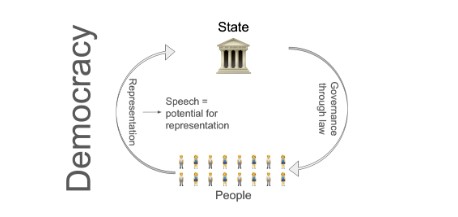

Let’s return to the freedom of speech. The same conflict holds. For the sake of democracy, freedom of speech is essential. Without it, not only will we all be less informed and knowledgeable about the affairs of the state but we will also be unable to participate in the democratic process. Democracy means not only voting to elect those who will represent us but also actively participating in the political process and advocating for our interests. And the dominant way of representing ourselves is through speech. Not only through words that express what we want, but arguments that defend and justify what ought to be. So the necessity of freedom of speech in a democratic state seems straightforward. We can add it to our diagram:

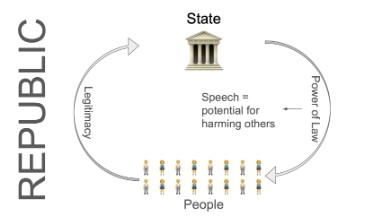

Similar to public assemblies for government criticism, which come with the condition that they remain peaceful, the freedom of speech also presents a potential danger to the republic. Why is this? Because speech is not wholly distinct from action. When communicating, it’s not just about stating facts or offering neutral descriptions. Language holds immense power. It goes beyond just reporting or describing, as it can be used to issue commands, ask questions, and make declarations. For example, when a priest or judge declares a couple married, it carries legal significance. Similarly, when one nation declares war on another, it marks the beginning of a war. Words have far-reaching effects, often beyond immediate understanding. Without limits, free speech could be used to undermine the very authority that upholds it. Moreover, speech can cause harm, not only by offending or hurting feelings but also by inciting physical harm or inflicting psychological trauma. The fear of consequences can often be a more potent motivator than the consequences themselves. In summary, words have real power and can cause genuine harm. Therefore, unrestricted freedom of speech poses a significant threat to the state, as the state is responsible for maintaining peace and is fundamental to a republic. As long as the peace of the population is the responsibility of the state and the central legitimizing feature of the republic, the unlimited freedom of speech is a real threat to the state. We can add it to our diagram like this.

If we now look at both functions of speech side-by-side, we see the contradiction front and center: the freedom of speech is necessary for the state because it’s democratic, and destructive of the state because it’s a republic. The freedom of speech is both a source of representation and a potential for harm. It would be easy if we could distinguish positive speech that serves as political representation from negative speech that is a potential for harm. But the reality seems to be that this distinction doesn’t hold. A decision must be made to identify which forms of speech that are harmful and politically relevant will be allowed and which will be prohibited.

Now, let us turn to the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case, Schenck v. United States, to see how the Espionage Act of 1917 was used to oppose and limit the First Amendment right to freedom of speech. By analyzing this case in the context of the contradictions inherent to democratic republics, we might adjudicate, interpret, and determine what the correct balance of statehood ought to be.

From the Landmark Cases eReader, we learned that Charles Schenck and Elizabeth Baer were convicted of violating the Espionage Act of 1917 for encouraging citizens to dodge the draft through the circulation of pamphlets. Appealing this verdict, Schenck and Baer claimed that the conviction of their actions violated the First Amendment. Thus the stage was set to evaluate and reinterpret the importance and significance of the freedom of speech when that speech is perceived as potentially harmful for the state.

From the point of view of Schenck and Baer, their First Amendment right was violated for the sake of the US’s involvement in a foreign war. But from the point of view of the US, in favor of which the court eventually ruled, Schenck and Baer’s speech could potentially have the effect of creating a disadvantage for the U.S. in World War I. Since war is a threat to national security, it is a small leap to argue that Schenck and Baer’s speech posed a potential threat to national security. By ruling against Schenck and Baer and upholding that the Espionage Act did not violate the First Amendment, the court effectively limited the scope of the First Amendment.

In addition to interpreting this Landmark Case as a limitation of the freedom of speech and an extension of the state’s power, we can also interpret it as a philosophical pronouncement of what the proper balance ought to be between the democratic value of the freedom of speech and the requirement for a republic to secure and control its population. What is significant about this case is that, for the first time in US history, the freedom of political speech was restricted, making it a Landmark Case.

Interestingly, the nature of the speech under dispute was clearly political. So it could not be successfully argued that Schenck and Baer’s freedom of speech was irrelevant to the practices of democracy. However, Justice Holmes alluded to such an argument when he compared their actions to shouting “Fire” in a crowded public space. In this situation, the nature of the speech considered (shouting “Fire” in a public space) does not admit any political significance. Shouting “Fire” in this situation does not reflect personal or group beliefs about community governance, so it does not qualify as political speech. Therefore, it strongly supports the case for restricting freedom of speech in this specific context. Schenck and Baer were addressing a political issue by expressing their opinion against the US involvement in WWI and suggesting a course of political action by advocating against the military draft. The use of the analogy of shouting “Fire” in a public space to describe their actions seems to be inappropriate. Instead, what we see in Schenck v. US is the limitation of political speech for the sake of state power. Thus the ruling that Justice Holmes made was not a mere application of law, but a new interpretation of the First Amendment.

Review Questions

- Why does rebellion need a reason? Who needs this reason?

- What is the meaning of freedom of speech as it relates to statehood and individual power?

- Why is the Bill of Rights essential for protecting individual freedoms in the United States?

- What was the central issue in the Schenck v. United States case, and how did the Supreme Court’s decision define the limits of free speech under the First Amendment?

For further exploration, please refer to the related assignment on the right to freedom of speech in a democratic state, focusing on its inherently ambiguous and conflictual nature.

About the author: Jonathan Berk is a professor in the Philosophy department at John Jay College of Criminal Justice

- All quotes from the Declaration of Independence are taken from “The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States,” from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. (http://www.uscis.gov) ↵

- Ruthann Robson . (n.d.). Introduction to the first amendment. In John Jay College Social Justice Landmark Cases e-Reader. Retrieved July 24, 2024, from https://pressbooks.cuny.edu/landmarkcases/chapter/introduction-to-the-first-amendment/ ↵