Should catcalls be criminalized? A brief comparison of the USA and Spain

M. Victoria Pérez-Ríos

Issues/Topics Covered in this Chapter

- Examine catcall data and regulations

- Assess the most significant arguments against catcall criminalization

- Federal catcall regulation in the USA

- Relevant recommendations to reduce the negative effects of catcalls

INTRODUCTION: MY PERSONAL EXPERIENCE

Reading data on catcalling in the USA and Spain brought back memories of my own experiences. It’s striking how similar they were to other women, despite the cultural differences. While I was fortunate enough not to endure daily harassment, the occasional catcalls still had a significant negative impact on me. They made it clear that men, whether alone or in a group, felt entitled to encroach on my right to move freely through the city. I constantly had to be prepared to defend myself verbally against these assaults, putting me in a constant state of “survival” every time I went out alone. This situation was not only unfair, but it also took a toll on my mental and physical well-being.

Based on my recollections of living in Zaragoza (Spain) from ages six to twenty-seven, at the time of my first catcall as hate speech, I was barely eleven years old and walking side-side with a classmate during a morning school trip. A middle-aged man interrupted our conversation by shouting “sluts” and “you are ready to have sex.” My sixth-grade teacher, still in her twenties, “hollered back” at him, “shut up.” “Aren’t you ashamed; these are young girls.” He didn’t listen to her and “justified” his engagement in the sexual harassment of two minors by referring to our clothing. OMG! We dared to wear Bermuda shorts. And we did it consciously because some of our peers decided, ahead of this trip, not to wear them to prevent abuse. My classmate and I thought this middle-aged man was disgusting but we felt vindicated by our teacher.

Fast-forward five years, around age sixteen, I was walking back home from school next to an open-air transportation hub when I started hearing honks, whistling, and nasty comments; some of the men were positioned at arm’s length. The catcalls surprised me because I walked past the same depot when I went to school in the morning without any problem. The “justification” for these verbal attacks was wearing a miniskirt. I felt so disgusted that I never wore it again. Let me be clear on this; I still wore miniskirts, just not that one. My mom and one of my female cousins laughed at me because it was a “natural” event to which they got used to at my age. As I did not “holler back,” impunity adds a bitter aftertaste to this catcall any time I recall it.

In between those years and afterward, I suffered catcalls in the street and other public spaces, like buses and parks, but I did “holler back.” I cannot remember any memorable catcalls in New York City (NYC), though. It could be that I was in my late twenties, ready for a verbal and stare battle, and moving relatively fast in streets packed with people. However, I can share an NYC catcall story courtesy of my first cousin’s son. Late at night on weekends, while returning home to the West Village from work at a restaurant, he used to witness older men catcalling young men at a popular skateboarding hangout. He assured me that if one of the men dared catcall him, he would have hit the catcaller. If females reacted similarly, not after one catcall but many, society would shame them for being hysterical and taking innuendo so seriously.

My personal story reveals a pattern that occurs every day all over the world. That is, mostly unaccompanied young females enjoying their freedom to be present or develop any legal activity in public spaces—including the street, parks, and public transportation—must endure auditory (whistles, honks, slurs, threats) and visual (obscene and intimidatory gestures) attacks by men they do not know. These men usually abstain from this kind of behavior if their potential targets are accompanied by adults, especially if the adult is a male. In addition, these men abstain from catcalling in the presence of their own family members. Furthermore, these men usually would be mortified if their spouses, daughters, grandmothers, mothers, or sisters were subjected to catcalls unless they were the ones inflicting them.

It took me some time to realize that catcalls had nothing to do with me. They were about men and their sense of ownership of the streets and of every woman who “dares” to walk through what men perceive as their private turf, aka, public space. Women rarely engage in this kind of behavior and, if they do, it rarely intimidates the men they target. Therefore, catcalls are another instrument of subjection of women by a patriarchal society that nobody wants to talk about. Even though everybody knows catcalls exist, it is all too common to hear excuses that blame the victims for a variety of reasons, including, women being too sensitive, women misunderstanding a compliment as a threat, women walking in dangerous spaces and at dangerous times of the day, and/or women dressing or behaving in a way conducive to being perceived as flirting.

Blaming the victims of catcalls violates the constitutional principle of “equal protection under the law” of the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution[1] applicable to public spaces. That means women have the right to walk in any public place, at any time of the day and night, and wear what they want within the parameters set by the law equally for both sexes without having to explain themselves. However, sexism is so ingrained in our society that while catcallers are free to violate women’s rights, including those of the female child; women who are just exercising their rights —including being bare-chested in public spaces—are arrested by police officers who don’t know the law.[2]

For example, since the People v. Santorelli (7 July 1992) decision of the highest court of New York State (NYS)—the Appeals Court —it is legal for females (women and girls alike) in NYS to bare their chests publicly just like men had been doing for years to beat the heat, get a tan, show their muscles … or just because they feel like. Before this decision, a topless woman in public could be punished with the crime of exposure of a person, according to § 245.01 of the New York Penal Law. Following is an excerpt from Associate Judge Vito J. Titone’s Concurring Decision reminding his colleagues on the bench that § 245.01 violated the principle of “equal protection under the law” between men and women and, thus, was unconstitutional:

[T]he People have offered nothing to justify a law that discriminates against women by prohibiting them from removing their tops and exposing their bare chests in public as men are routinely permitted to do. The mere fact that the statute’s aim is the protection of ‘public sensibilities’ is not sufficient to satisfy the state’s burden of showing an ‘exceedingly persuasive justification’ for a classification that expressly discriminates on the basis of sex (see, Kirchberg v Feenstra, 450 US 455, 461). Accordingly, the gender-based classification established by Penal Law § 245.01 violates appellants’ equal protection rights and, for that reason, I concur in the majority’s result and vote to reverse the order below (People v. Santorelli, 1992, Last para.).[3]

According to United Nations Women, no country has achieved gender equality, and the COVID-19 pandemic has caused regression in crucial areas.[4] Despite evidence of ongoing institutional discrimination against women (including biologically or self-identified females, underage females, or girls) many sectors of society worldwide continue to dismiss sexism and justify the unequal treatment of women as a biological reality. This extends to the lack of protection against hate speech. This chapter focuses on catcalls and the controversy surrounding their criminalization. Specifically, this chapter compares the USA (where absent a specific Supreme Court decision, catcalls as speech are constitutional) and Spain, where catcalls have been criminalized as street harassment since 2022. The comparison is relevant because, while freedom of speech is more limited in Spain than in the USA according to the 2021 Free Speech Index, Spain has a score of .73 and the USA of .78,[5] Spain outperforms the USA in gender equality according to the 2023 Global Gender Gap Index Rankings Spain ranks 18 and, the USA, 43.[6]

If you want to share your catcall story with a wider audience, the government of the City of New York provides this resource: Resource Guide on Street Harassment

If you or someone you know need support following a catcall experience, which is a subset of the wider term “street harassment,” contact the following:

The Women’s Center for Gender Justice at John Jay provides counseling regarding gender-based violence and sexual harassment.

The National Street Harassment Hotline, or call, English and Spanish, (855) 97-5910

CATCALLS: CONCEPT AND RELEVANCE

The absence of a consistent, universally accepted definition of catcalls and the ongoing disagreement over their nature underscore that catcalling primarily represents a gendered issue — a spectrum of sexual violence, sexual terrorism (aimed at keeping women in their place), or breaches of urban ‘civil inattention’ norms — which complicates the potential for criminalizing catcalls.[7]

Moreover, “[d]efinitions for catcalls reflect the range of disciplines from which scholars have examined this phenomenon. … Without a unifying approach to studying catcalls, the terminology used to identify catcall behavior also varies”.[8] Yet there is an agreement on several actions with sexual connotations that can facilitate a future criminalization of activities affecting the constitutional and human rights of, mostly, women.

Although a more comprehensive approach to researching catcalls is necessary, societies in the twenty-first century are slowly realizing that catcalls are a harmful social construct and are beginning to invest more resources in documenting and examining them. [9]

As a result, there is evidence, albeit incomplete, of (1) the mental, physical, and economic consequences of exposure to catcalls and, (2) the link between catcalls and more serious crimes, including rape and homicide. For example, in March (2024) a catcaller knifed to death a nineteen-year-old woman in NYC. She and her twin sister found refuge from the catcaller at a deli but he ambushed them outside of it.[10]

What Are Catcalls?

In this article, I focus on speech-related—verbal and non-verbal—catcalls experienced by women—a term that includes girls or females under eighteen and transgender females. Catcalls can be defined as “unwarranted sexual attention from strangers. … The most common example … is probably whistling, but there are many different types of catcalling. It may include yelling, car honking, sexual gestures, invasive questions, pet names, staring, and more”.[11] Other types of catcalls include “continuing to talk to someone after they have asked to be left alone; flashing; intentionally invading personal space or blocking the way; … sexist, racist, homophobic, transphobic slurs, or any comments insulting or demeaning an aspect of someone’s identity; and showing pornographic images without someone’s consent”[12] Catcalls are not compliments.[13]

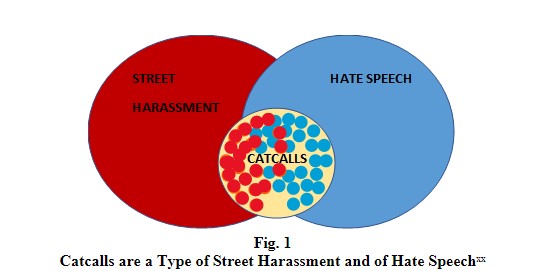

Catcalls constitute a type of hate speech and street harassment (see Fig. 1 below for the relationship between these three concepts). As catcallers target victims based on their innate characteristics—including sex/gender, race, ethnicity, religion, disability, age, and social status—using words, sounds, and gestures, catcalls are a form of hate speech. Moreover, as catcalls occur in public spaces—such as streets, public transportation, restaurants, and shopping and entertainment venues—they invade the victim’s space and often reference the victim’s physical appearance. Therefore, catcalls are also a form of street harassment or a type of sexual harassment, the latter of which encompasses more physical actions as well.[14]

Whether a form of hate speech or street harassment, catcalls can occur at any time of day or night. Even though some catcalls (e.g., “Hi, sunshine” or “You are pretty”) may seem harmless, they come from strangers rather than people known to the victim. These catcalls are projections of the catcaller’s power and persist until the target reacts in some way. Moreover, catcalls often include intimidating language, either explicitly or implicitly, due to the unequal power dynamic between catcallers and victims. For example, a group of men yelling “You are pretty” at a woman in an isolated area is implicitly threatening; she doesn’t know whether they are joking, but they know she is at their mercy. Additionally, women are exposed to numerous catcalls throughout the years, especially from ages 10 to 30, and expect them with dread given their potential to precede assault or, worse, rape. This risk is not imagined; according to the 2015 National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey in the USA, 1 out of 5 women in the USA have suffered attempted rape or rape compared to only 1 out of every 38 men.[15]

In theory, anyone can be a perpetrator or a victim of catcalling. However, the reality is that most of the perpetrators are men, either individually or in groups, and most of the victims are women. Even when the victims are males, the majority of the catcallers are also men. A 2015 survey of nearly 5,000 women living in the USA reveals that catcalling is not only prevalent in developing countries but also widespread in the USA. Surveys conducted by Cornell University’s New York state-assisted Industrial and Labor Relations and the nonprofit organization Hollaback! revealed that nearly “85% of American female respondents reported experiencing street harassment before the age of 17, and nearly 70% before the age of 14.”[16]

Furthermore, catcalls affect pre-pubescent females at a high rate. In the USA, more than 10% of women have been exposed to catcalls before their eleventh birthday.[17] Although many perpetrators hide behind the excuse “she looked older,” this is absurd when the victims are clearly children, often wearing school uniforms. With this excuse, perpetrators aim to circumvent the current norm that child endangerment is a serious crime, while also asserting their perceived right to prey on any female who is or appears to be eighteen or older. In our society, the latter is more palatable since adult women are considered “legal” sexual beings.

In addition, women belonging to two or more minority groups simultaneously apart from being female are harassed at higher rates.

In addition, women belonging to two or more minority groups simultaneously apart from being female are harassed at higher rates.

Studies conducted in the Safe Cities and Safe Public Spaces with Women and Girls Global Initiative reveal specific challenges women and girl transport users face. …[Y]oung women, women with disabilities, [transgender or belonging to the LGBTQ+ community in general], and ethnic minority women are often at greater risk of sexual violence in and around public transportation. … [Women] experience such violence during the daytime and evenings.[18]

That is why Kimberlé Crenshaw’s theory of intersectionality is useful to address catcalls.

Why Are Catcalls Relevant?

The #MeToo movement gained popularity in 2017 and brought attention to sexual violence against women (VAW). Although rape and domestic violence are serious forms of VAW, street harassment, particularly catcalling, is the most common.[19] Despite this, in-depth analysis of catcalls is often missing from public discourse. There is a pervasive myth that catcalls are harmless and are sometimes confused with harmless flirting. For some, women have no right to walk the streets without being catcalled and sexually objectified.

In a 2014 YouGov.com survey, it was found that around 20% of the American population considers catcalls to be compliments, and this percentage increases to one-third for the 18 to 30-year-old age group.[20]

However, it’s important to note that catcalls should not be seen as flirting, as flirting involves consent and mutual respect, while catcalls are non-consensual and can disrupt a woman’s daily life, such as when she’s going to school or exercising in the park, or when consent has been clearly denied, such as when a woman at a bar turns down the catcaller. The same survey indicated that 55% of Americans view catcalling as harassment, but 65% of them believe that the “police should not ticket or arrest catcallers.”[21] This shows that a significant portion of those who recognize catcalling as harassment do not think it warrants police intervention. This may indicate an unconscious bias against women.

Not surprisingly, according to the Gender Social Norms Index (GSNI), almost 90% of the world (men and women alike) are biased against women “along four key dimensions: political, educational, economic and physical integrity” including the USA and Spain (United Nations Development Programme, 2019, pp. 3 and 25 (Table 1: Spain and the USA)).[22] For most people, men have the right to catcall; women, their main target, just need to stop being so thin-skinned. Anecdotally, after asking a speaker—a female prosecutor—about catcalls against women at a John Jay College of Criminal Justice online workshop on hate speech and hate crimes, she asserted that bothering the police about catcalls was a waste of their time unless the catcall was accompanied by another “potentially criminal” activity.[23] Her view exacerbates two problems. First, low reporting affects data on the prevalence and seriousness of catcalls. And second, weak enforcement of catcall regulations in New York. See, below, the USA case study.

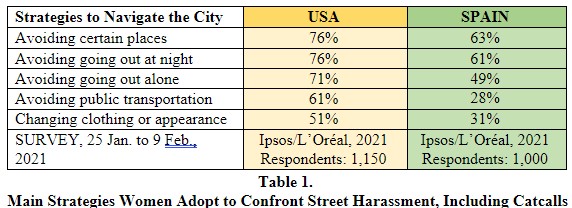

Contrary to the previous perspective, catcalls are relevant and merit policing for the following relevant reasons: (1) Violating fundamental rights. (2) Producing physical and mental harm. (3) Generating financial loss. And (4) being precursors to more serious crimes. First, catcalls constitute a discriminatory practice that violates, among others, women’s individual rights to equal treatment (Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution), freedom of movement, privacy, security, and accountability. In addition, women adopt strategies to prevent catcalls (see: below, Table 1) that are evidence of the violation of women’s collective right to the city or “the right of all inhabitants, present and future, permanent and temporary, to inhabit, use, occupy, produce, govern and enjoy just, inclusive, safe and sustainable cities, villages and human settlements … essential to a full and decent life.”[24]

The survey was based on interviews with a representative sample of the population of each country; it was agreed that there should be at least 400 males and 600 females.[25]

Table 1 lists the most common strategies. Other findings include specifically stopping doing an activity, changing schools, dropping a course or even dropping out of education totally, and rejecting a job offer. Some data shows that these other strategies occur in less than 5% of the cases in the USA.[26]Women adopt several of these strategies simultaneously, not just one of them.

Second, catcalls produce mental and physical harm[27] and can worsen preexisting ailments too.[28] Although some studies have a limited universe (under 300 respondents), they have been conducted since the 1990s globally and they prove at least the following types of harm: (1) Self-objectification. As a result, “the objectified see themselves … [as] seen by their objectifiers: as lacking warmth, competence, morality, and humanity.”[29] (2) Anxiety, depression, and less quality of sleep.[30] (3) Eating disorders which can have severe physical consequences.[31] And (4) Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).[32]

Third, it’s important to consider the financial impact of the mental and physical harm caused by catcalling. By hearing more about women’s experiences and understanding their effects, it might be possible to calculate the overall income loss for the average catcalling victim in the next decade. Areas of impact include (1) spending money on private transportation and taking longer routes to feel safer, (2) missing out on networking and job opportunities, especially when traveling alone, and (3) affecting academic and professional careers; students may experience lower GPAs and take longer to complete college.[33]

Not only do victims suffer, but their families and communities also suffer from loss of income and increased expenses. For example, many catcalling victims may stop volunteering and going out for fun, may have to take sick days, and may require more healthcare resources.

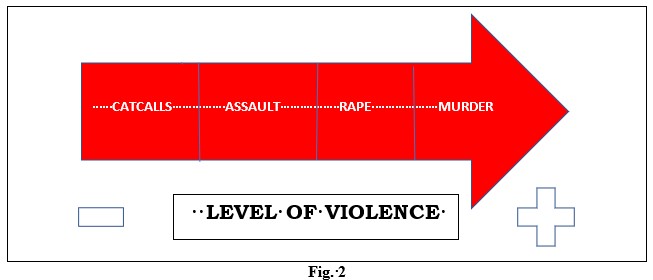

Fourth, catcalls can be the precursors to other crimes. This link is visible when catcalls are seen as “fall[ing] along a spectrum of violence. It can start as verbal harassment and escalate to sexual assault and rape — and even murder.”[34] See: below, Fig. 2.

Catcalls As Part of a Spectrum of Violence Against Women[35]

Even though the social trivialization of catcalls obscures their role as a gateway to rape and homicide, the following seven cases from the last decade show the assault, rape, and killing of a woman that started with a catcall:

CATCALLED, RAPED AND KILLED

November 23, 2019: Ruth George, 19 years old, was raped, strangled, and left to die after not paying attention—or not engaging in any way—to a catcaller who followed her up to her car inside a parking lot. She was trying to get home alone after attending a professional meeting at the University of Illinois at Chicago where she was a student.[36]

CATCALLED AND KILLED

March 17, 2024: Samya Spain, 19 years, old, was stabbed to death outside a deli in Brooklyn, NY after rejecting a catcaller inside a deli where she was with her twin (stabbed too but only injured) and her brother. The catcaller was asked to leave Spain alone and had to be forced out of the deli but waited in the surrounding area with friends.[37]

January 22, 2016: Janese Talton Jackson, 29 years old, was shot dead after rejecting repeated requests from a catcaller, inside and outside a bar in Pittsburg. The catcaller “followed her out and ‘positioned himself against her backside in a sexual manner.’ The employee said Jackson pushed [catcaller] slightly away and told him to ‘chill’”.[38]

September 5, 2016: Tiarah Poyau, 22 years old, was shot dead “for having the nerve to tell a man to stop grinding against her”[39] during the J’ouvert Festival in Brooklyn, NY. Poyau was attending the festival with three friends but was behind them when the catcaller shot her at close range; the bullet went through her eye.

October 5, 2014: Mary “Unique” Spears, 27 years old, was shot dead (five other people injured) after rejecting the request of a catcaller when she left the American Legion Hall in Detroit; she was attending a family gathering after a funeral service and her fiancé was with her (Abbey-Lambertz, 13 November 2014/Updated 6 December 2017).[40]

CATCALLED DAUGHTER, FATHER KILLED

March 20, 2014: Michael Tingling, 59 years old, was punched several times and died from cardiac arrest after defending his fifteen-year-old daughter from a man who made inappropriate gestures while brushing against her shoulder. Tingling was picking up his daughter from school in Chicago.[41]

CATCALLED AND INJURED

April 16, 2021: Meairra Mansaray, 24 years old, was shot in the leg and left with a shattered tibia after she rejected the catcalls shouted by a man from a car in Atlanta; her boyfriend asked the catcaller to stop too. When the catcaller continued, Mansaray and her boyfriend tried to escape using their scooters but the catcaller fired five shots.[42]

Do you want to know more? Read Deirdre Davis. (1994). The Harm That Has No Name: Street Harassment, Embodiment, and African American Women.

CATCALLS IN THE USA AND SPAIN

Catcalling, considered hate speech, is legal in the USA but has been criminalized in Spain since 2022. To facilitate the transfer of international policy from Spain to the USA, it’s important to compare the two countries. Their main similarities include: (1) both are advanced industrialized democracies committed to equality and non-discrimination and (2) decision-making is organized according to federalism. The USA is one nation with fifty states and more than 90,000 local governments that share power,[43] while Spain has one national government, 17 autonomous communities, and two autonomous cities.[44] Also, (3) both countries share similar rankings in the 2023 Gender Social Norms Index (GSNI) on biases about women’s physical integrity.[45]

Their main differences include (1) Their relationship to International Law (IL). While the USA is a dualist country where ratified international treaties are non-self-executing, Spain is a monist country where treaties are automatically part of the legal system but need adaptation. (2) Spain has international and domestic duties to fight against sexism as a party to the 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and as per Article 14 of the Spanish Constitution[46] but not the USA. And (3) Spain is closer to the German model of federalism with a stronger central government facilitating nationwide solutions.[47]

In each case study, I will first examine the catcall data, with some important considerations. The data is somewhat old and is mixed with a broader category of street harassment. However, it is still valid as catcalls are the most common form of street harassment. Secondly, I will focus on regulating catcalls as verbal and non-verbal speech. Other activities such as taking pictures, following, stalking, groping, and touching are beyond the scope of this article. I will also analyze the constitutionality of hate speech at the federal level in the United States and the variable regulation of catcalling at the state and local levels, specifically focusing on New York City, the location of John Jay College. For Spain, the focus will be on International Law (IL) and the national legislation set for 2022 that criminalizes street harassment. Lastly, I will assess the main arguments against the criminalization of catcalls.

Catcalls Constitutionally Accepted: The Case of the USA

The USA is a party to the 1966/1976 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) that imposes the duty of non-discrimination and enforcing equality between men and women (Articles 2 and 3). However, the constitutionality of hate speech and the failure to approve the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) and to ratify the CEDAW affect the potential regulation of catcalls in the USA at the national level.

● Relevant Data on Catcalls with a Focus on Underage Women

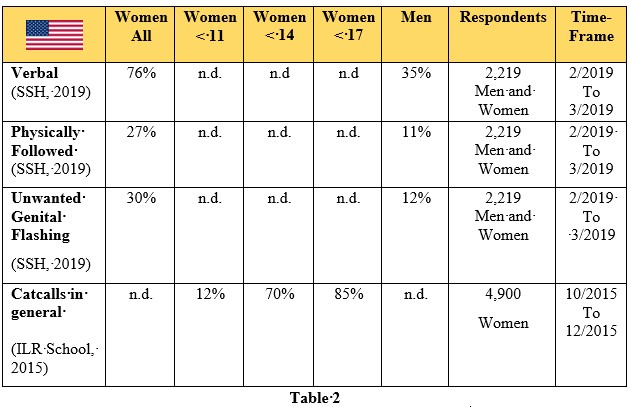

Absent a comprehensive survey on catcalls in the USA, I compiled data from different surveys. See: Below, Table 2. According to a 2019 NORC/University of Chicago survey of more than 2,000 people, over three-quarters of all women and slightly over a third of men “experienced verbal sexual harassment.” In addition, over a fourth of all women and over one-tenth of all men “were physically followed.” Moreover, less than a third of all women and over one-tenth of all men “faced unwanted genital flashing”.[48] A previous 2015 survey of close to 5,000 females shocked some because it showed that 12% of females under the age of eleven suffered catcalls. Moreover, before reaching fourteen, 70% of women have experienced catcalls and before celebrating their seventeenth birthday, 85% of women are the victims of catcalls.[49]

Data on Catcalls in the USA, 2015 and 2019[50]

A 2019 Stop Street Harassment informal online survey with 245 respondents (94% identified as female, 2.5% identified as male, and 2.5% as nonbinary) confirmed that many catcalls equal child endangerment as follows: (1) Most females, around 70%, are first catcalled before their fourteenth birthday and 18% when they were younger than eleven years old. And (2) many catcallers target females at least a decade and a half younger than themselves (55% were young children when experiencing their first catcall and remember the catcallers being grown-up men, 30 years old or older. Specifically, “8% said the men were in their 50s, 20% said the men were in their 40s [and] 27% said the men were in their 30s” —creating a situation of increased danger because of the overwhelming differential in physical strength and life experience.[51]

- Regulation of Catcalls with a Focus on Verbal and Non-Verbal Speech

Focusing on catcalls as verbal and non-verbal speech, there is no federal law or SCOTUS decision addressing catcalls. Nevertheless, as it is a subset of hate speech, you can find and read relevant landmark cases on hate speech in this e-reader: You can say that but should you? Do We Have a Right to Hate Speech? Concept and Constitutionality of Hate Speech in the U.S. By M. Victoria Pérez-Ríos

In sum, catcalls (like any other type of hate speech) are constitutionally protected, unless the catcalls include profanities and/or pornography, for two main reasons, (1) the doctrine of fighting words is rarely used anymore and (2) the threshold to prove incitement to commit a crime is remarkably high.

The constitutional protection of catcalls as a type of hate speech at the federal level brings forth the importance of state legislation. The Tenth Amendment to the US Constitution recognizes that “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”[52] States reserved powers coincide with policing power.

We deal, in other words, with what traditionally has been known as the police power. An attempt to define its reach or trace its outer limits is fruitless. … Subject to specific constitutional limitations, when the legislature has spoken, the public interest has been declared in terms well nigh conclusive. In such cases, the legislature, not the judiciary, is the main guardian of the public needs to be served by social legislation, whether it be Congress legislating concerning the District of Columbia … or the States legislating concerning local affairs (…).

Public safety, public health, morality, peace and quiet, law and order –– these are some of the more conspicuous examples of the traditional application of police power to municipal affairs (Berman v. Parker, 1954, p. 32).[53] [Emphasis Added].[54]

Based on Section 2 of this chapter, catcalls affect “public safety, public health, morality, peace and quiet, law and order” or the crux of policing powers. Therefore, state governments retain the power to regulate catcalls but only in a manner respectful of freedom of speech as incorporated in the 1925 SCOTUS decision Gitlow v. New York [55]based on the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution (Congress Research Service, n.d.).[56]In a unanimous opinion, SCOTUS asserted, “For present purposes, we may and do assume that freedom of speech and of the press which are protected by the First Amendment from abridgment by Congress are among the fundamental personal rights and ‘liberties’ protected by the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment from impairment by the States” (Gitlow v. New York, 1925, p. 666).[57]

Currently, the regulation of catcalls throughout the USA is characterized by its variety (Brinlee, 2 August 2018).[58] Since John Jay College is in NYC, I focus on the New York State Penal Law (NY Penal L). Although the NY Penal L does not criminalize catcalling per se, it criminalizes activities constituting catcalls as hate speech or as street harassment. As a type of hate speech, catcalls are criminalized in Part 3, Title M or “Offenses Against Public Health and Morals” and Title N or “Offenses Against Public Order, Public Sensibilities and the Right to Privacy” of NY Penal L (The New York State Senate, 10 March 2023, NY Penal L, Part 3, Titles M and N).[59]

Catcalls as hate speech amount largely to the following “violations” or offenses that are less than a misdemeanor: Disorderly conduct, harassment in the second degree, loitering, loitering for the purpose of prostitution, and exposure of a person. These violations can be punished with a fine of up to $250 and/or fifteen days in jail (The New York State Senate, 10 March 2023, NY Penal L, Part. 3, Title N, Article 240 §20/25/35-37 and Article 245 §01).[60] Due to the light punishment, there is not much incentive to report these incidents to the police.

The exceptions to this light punishment are (1) patronizing a prostitute—catcaller treats the victim as a prostitute by asking how much or requesting a sexual service. If the victim is (a) fifteen or older, it is classified as a class A misdemeanor punished with a fine of up to $1,000 and/or up to one-year imprisonment. (b) If the victim is under fifteen, it becomes a class E felony punished with “No Jail, Probation, 1 1/2 to 4 years”; and if the victim is younger than eleven it is punished as a class D felony penalized with “No Jail, Probation, 2 to 7 years” (The New York State Senate, 10 March 2023, NY Penal L, Part 3, Title M, Article 230 §02-06 and Part 2, Title E, Article 70).[61] And (2) the class B misdemeanor of public lewdness, punished with a fine of up to $500 and/or up to three months in jail (The New York State Senate, 10 March 2023, NY Penal L, Part 3, Title N, Article 245 §03).[62]

One drawback to the somewhat robust punishment attached to the misdemeanor and the felony of patronizing a prostitute is the defense based on “the defendant did not have reasonable grounds to believe that the person was less than the age specified” (The New York State Senate, 10 March 2023, NY Penal L, Part 3 Title M, Article 230 §07).[63] In addition, the NY Penal L criminalizes actions that are part of catcalls as street harassment and include taking photos, following, and groping but they are not the focus of this article (Stop Street Harassment, n.d.).[64]

Catcalls Criminalized Nationally: The Case of Spain

Contrary to the USA, Article 14 of the Spanish Constitution recognizes explicitly “the principle of equality … without discrimination based on … sex”[65]and Spain is a party to the ICCPR, the CEDAW, and the 2011 Council of Europe’s Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence (aka- the Istanbul Convention). Thus, it is easier for Spain to regulate catcalls nationally.

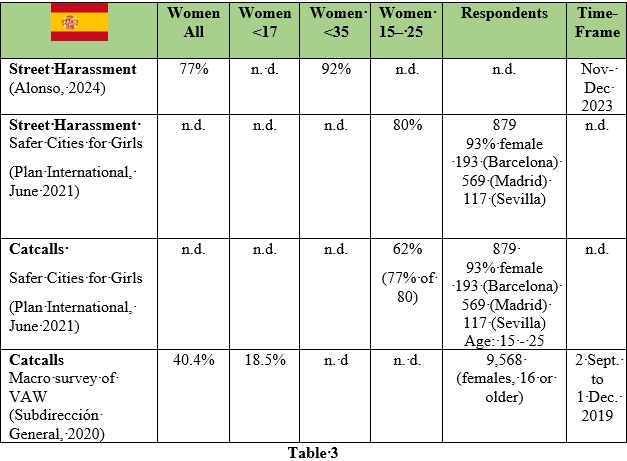

- Relevant Data on Catcalls with a focus on Underage Women

The government-sponsored 2019 Macro-Survey on VAW or “macro-encuesta sobre violencia contra la mujer” covered comprehensibly the spectrum of violence, including catcalls. The caveat is that although it asked catcall-specific questions, it included a question about harassment in the workplace which affected less than 3% of cases of harassment. This survey confirms that almost all the perpetrators are men (98%); almost 80% unknown to the victim,[66] and that the most common catcalls are ogling, sexual jokes, demanding personal information, propositioning sex, and indecent exposure.[67]

This Macro-Survey found surprisingly low percentages of catcalls because out of 9,568 respondents —all women older than fifteen living in Spain—only 40.4% experienced catcalls.[68]The researchers explained the results by pointing out that women over 65 years old “may have forgotten … or not considered their past experiences as catcalls.”[69] It is a plausible explanation because almost a quarter of the respondents were over 65 years old (24.6%) or a higher percentage than all the respondents under 35 years old (23.4%) who are subjected to more catcalls and more recently[70] Another plausible explanation could be that respondents felt uneasy sharing data on catcalling—dismissing their experiences as trivial— after responding to questions about more serious violence like assault and rape.

Data published in 2021 and 2024 reveal a higher incidence of catcalling in Spain. In 2021 Safer Cities for Girls reported that 80% of women 15- to 25-year-old suffer from street harassment and 62% from catcalling.[71]The 2024 Ipsos/L’Oréal survey conducted in 2023 confirmed that 77% of all women in Spain suffer from street harassment of which catcalls are its most prevalent subset. Moreover, physical street harassment is oftentimes preceded by catcalls. This higher percentage of prevalence could result from the two surveys’ focus on street harassment and the respondents of the 2021 survey being 15- to 25-year-olds; younger generations are more aware of street harassment as not being “natural” because it is a behavior being questioned now publicly. The percentage of women who suffer street harassment is higher, 92%, for women under 35[72] See: below, Table 3. Moreover, in 34% of the cases, there is more than one male catcaller.[73]

- The Law on Street Harassment with a Focus on Verbal and Non-Verbal Speech

According to the CEDAW (ratified by Spain on 16 December 1983)[75] Spain must aim at fulfilling gender equality. To that end, Spain has the duty “to take all appropriate measures: (a) To modify the social and cultural patterns of conduct of men and women, with a view to achieving the elimination of prejudices and customary and all other practices which are based on the idea of the inferiority or the superiority of either of the sexes or on stereotyped roles for men and women.”[76] Taking into account that the ubiquitous presence of catcalls is based on men‘s sense of superiority over women and gender stereotypes regarding the use of public spaces, a focus on making catcallers accountable for their activities will mean a great advance toward gender equity.

Moreover, when Spain ratified the Istanbul Convention on 18 March 2014,[77] the Spanish government assumed the explicit obligation of punishing catcallers. In the words of the Convention, Spain must “ensure that any form of unwanted verbal, non-verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature with the purpose or effect of violating the dignity of a person, in particular when creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment, is subject to criminal or other legal sanction.”[78] It is important to underline that the Convention limits the scope of punishment of catcalls to (1) “unwanted … conduct of a sexual nature.” Thus, if there is consent, these conducts are not catcalls. And (2) to the most dangerous cases or those “creating intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment.”

Notwithstanding these duties to advance gender equality in general and to neutralize catcalls in particular, it took Spain until late 2022 (via Organic Law 10/2022 of 6 September 2022 of Comprehensive Protection of Sexual Freedom or “garantía integral de la libertad sexual,” known as the law of yes means yes or “ley de solo el sí es sí”)[79] to adapt its criminal law to the Istanbul Convention. Other countries had criminalized street harassment earlier, as follows: Belgium (2014), Peru and Portugal (2015), Morocco (2018), and Argentina, Chile and France (2019).[80] The Spanish Organic Law 10/2022 regulating sexual freedom introduced the crime of street harassment in Article 173.4 (2) of the Spanish Penal Code as a minor offense against a person’s honor that is only prosecuted ex parte or when “the victim or the victim’s legal guardian requests it” (Article 173.4(3)).[81]

Article 173.4(2) does not list specific catcalls. However, it regulates verbal and non-verbal speech of a sexual nature—the essence of catcalls—by punishing “anyone addressing to another person expressions, behaviors or propositions of a sexual nature that create for the victim an objectively [average person standard] humiliating, hostile or intimidating situation and whose actions are not punishable with more severe offenses.” Since Art. 173.4(2) does not specify that this criminal offense must take place in the street, it extends its application to other spaces, including the Internet.[82] According to Art. 173.4(1), the punishment for this offense is “house arrest lasting from five to thirty days … or community service of five to thirty days or a fine of one to four months;” regarding fines, time is translated into a monetary amount.[83]

Art. 173.4(2) has a limited scope because it only applies to the most severe types of catcalls or those that “create an objectively humiliating, hostile or intimidating situation.” Contrary to the Convention of Istanbul[84] it does not apply to catcalls that create an “offensive” situation. Similarly to the USA where freedom of speech encompasses the right to offend. Furthermore, catcalls can only be prosecuted ex parte, according to Art. 173.4(3)[85] That is why, it is possible to reject two significant criticisms based on misinformation divulged to benefit the anti-Feminist agenda of the Right and Far-Right in Spain. First, the Spanish Far-Right party Vox affirmed that “it is a pity that we are going to lose what is a token of admiration and popular ingenuity.”[86] Actual “piropos”—pleasant, cheesy, hilarious, and even patronizing and fastidious—that do not target minors will live on because they are not punishable; they are not hate speech.

Second, men’s presumption of innocence is not violated because although the 2022 Spanish law of Comprehensive Protection of Sexual Freedom establishes consent at the center of any crime of VAW (or better said, her lack of consent) the victim of the catcall continues to bear the burden of proving that the author of the catcall “create[d] an objectively humiliating, hostile or intimidating situation.”[87] Moreover, even though most catcallers are men, any person can be accused of this crime.[88] It is important to underline that many who oppose the criminalization of catcalls because women do it, are only worried about the presumption of innocence of men.

It is too early to assess how Art. 173.4(2) will be enforced in practice, including which catcalls the judiciary will consider sufficiently serious to be punished. However, a judge in Sevilla already handed down the first street harassment decision on 15 June 2023. The victims were two young women; the perpetrator was a sixty-year-old man with a suspended sentence for sexually abusing a 13-year-old girl; the criminal activity included requesting sexual favors, flashing and masturbating repeatedly in front of the young women; and the evidence was cellphone recordings of his actions. The judge imposed a punishment of “thirty days of house arrest and 100 euros of ‘symbolic’ compensation of moral damages caused to the two young women” which seems too benign but Spain is not a retributionist country and the accused apologized to the victims.[89] Since the two women had to prove his actions were humiliating for the average person, the implementation of Art. 173.4(2) does not violate men’s presumption of innocence. NYS would have punished his verbal and non-verbal catcalls too.

Art. 173.4(2) has been used by the municipal police in Barcelona to guarantee accountability to a female taxi driver who reported that a 27-year-old male client started to masturbate inside her taxi; she taped him with a video system she had installed in the taxi.[90] There is no sentence yet.

C. Significant Arguments Against Regulating Catcalls: Assessment

In the past, many objected to regulating catcalls because it was difficult to identify the perpetrator and the actual action because catcalls oftentimes last seconds. Currently, technology like cell phones and security systems make it possible to have evidence of the catcall without the need for the police to spend time and resources investigating what happened. Although technological advances have made this argument irrelevant, I have found two significant types of arguments against the regulation of catcalls as hate speech. One type is related to the protection of freedom of speech as the preeminent right in a democratic system; it applies mainly to the USA. The other type is premised on the gender biases and stereotypes of any patriarchal society; it applies to the USA and Spain.[91]

(1) The protecting free speech argument. For almost a century—since Gitlow v. New York (1925)—SCOTUS has given freedom of speech a preeminent position in the system of protection of individual rights of the USA because, without freedom of speech, other rights are left without protection. As a result, many experts use the slippery slope argument to oppose the regulation of any type of hate speech, including catcalls, as regulation could open the gates to censor dissent, especially racial minorities affected by structural discrimination. For example, an expert from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) fears that,

Disorderly conduct and ‘obscene gesture’ laws … can be (and often are) misused against lawful protesters, people criticizing the police, and individuals filming officers in public. Similarly, expansively interpreting such laws to cover catcalls could … be used pretextually as part of ‘broken windows’ policing, which disproportionately impacts communities of color.[92]

For more information explore this Social Justice eReader chapter: You can say that but should you? Do We Have a Right to Hate Speech? Concept and Constitutionality of Hate Speech in the U.S.

A more extreme version of the slippery slope argument is defended by libertarians. For example, the President of the Rutherford Institute connects regulating speech that we dislike, including hate speech, with the doom of democracy and the establishment of an Orwellian world. And, according to him, the descent of the USA into dystopia has already begun. He parallels our current situation with Nazi Germany’s dystopia that started when society remained apathetic to the rounding up of Socialists but “[i]n our case [the USA], … it started with the censors who went after extremists spouting so-called ‘hate speech,’ and few spoke out—because they were not extremists and didn’t want to be shamed for being perceived as politically incorrect.”[93]

(2) The gender bias or sexist argument. It is based on the superiority of men over women. As a result, men are the standard, and their needs and perspectives are favored in society; women must conform to male expectations, especially in the public sphere. The most recurrent examples in both countries, the USA and Spain, include the following: (1) Identifying catcalls with compliments—and “piropos” in Spain or short flirting remarks done “with flair”— no matter how crude, demeaning or intimidating and whether the target is underage or not; (2) rejecting how commonplace catcalls against females under 30 years old are, and how early they start; (3) as a consequence of the previous one, underlying that men can be victims and that women can be perpetrators of catcalls too without mentioning the power differential between men and women, that most catcallers are men and that most victims are female; (4) dismissing the severity of catcalls, be it their effects on victims and/or as precursors to more violent actions; and (5) blaming the victims for not knowing how to behave, dress or react in public places.

In the USA, arguments based on freedom of speech are legally sound because speech has preeminence in the constitutional system of the USA. However, SCOTUS allows regulation of speech when it endangers our form of government or children, for example. That is why, using precise language and training law enforcement seriously in Diversity, Equality and Inclusivity (DEI) principles, catcalls could be banned federally without undermining the constitutional rights to freedom of speech and non-discrimination, especially of racial minorities. For example, it seems highly improbable that many would argue that catcalls directed at children (in practical terms, the female child) under fifteen are protected speech and that grown men have a right to engage in catcalls of minors.

Arguments based on sexism— including the five examples listed before—dismiss available data on catcalls as irrelevant and are oftentimes accompanied by “constitutional talk” affirming that criminalizing catcalls is an attempt to violate men’s rights, including freedom of speech and the presumption of innocence — two sustaining pillars of liberal democracies like the USA and Spain. However, first, as mentioned, freedom of speech is not absolute and can be regulated. And second, the presumption of innocence is a procedural protection that applies to the accused, be it of actions already in the penal code or new crimes. Men being most of the catcallers is a fact, not an attack on men’s presumption of innocence. Notwithstanding this “constitutional talk,” sexist arguments are contrary to the USA and Spain’s constitutional and IL obligations as examined in each case study. Since gender bias is highly ingrained in our society, for me it poses the strongest obstacle preventing the regulation of catcalls federally.

CONCLUSIONS: SHOULD CATCALLS BE BANNED?

Summing up the relevant data from Sections 2 and 3, catcalls in the USA and Spain are first, a commonplace sexual and sexist practice, exercised primarily by men against the will of mostly women and their right to enjoy freely the public sphere. Second, men tend to target very young women—over 10% of women experienced their first catcall before their 11th birthday, and 75% before their 17th birthday. See: Above, Table 2&3. The targets were usually at least a decade and a half younger than the catcallers who operate in groups of two or larger in close to 38% of the cases.[94] The extreme power differential experienced in these situations explains why women understand catcalls as a clear and present danger to their security. And third, biases against women allow society to trivialize catcalls, the most prevalent form of VAW.[95]Thus, justifying impunity for practices that can negatively affect all aspects of a victim’s life and be a precursor to rape and even death.

Consequently, catcalls are a prime example of discrimination against women. I believe that if similar attacks targeted young men under 17, even at lower rates, there would be social alarm. Considering that the USA, like Spain, is a Western liberal democracy premised on the principle of equality and non-discrimination based on sex/gender, among other inherent characteristics, my main conclusion is that the USA should regulate catcalls as hate speech at the federal level to guarantee women equal protection under the law. Annabella Taylor Barget—one of my spring 2024 POL101.04 students —gave a compelling reason in favor of regulating catcalls explaining the core meaning of a catcall as a privilege. She replied to another student’s post, “Hi Anthony! I completely agree with wanting catcalling to be forbidden within the Constitution. It’s a form of speech that has no real benefits to the receiver, or to anybody, it’s only pleasurable to the individual who initiates the catchall.”[96]

The regulation of catcalling is important in the USA to ensure women can exercise their rights equally. However, it should be done in a way that respects freedom of speech as per the SCOTUS’s constitutional doctrine, while also protecting women’s right to use public spaces without being subjected to men’s sexist and sometimes misogynistic behavior, which goes against the US Constitution. As seen in the case study of Spain, the 2022 Spanish law criminalized only the most severe catcalls or those that are “humiliating, hostile, or intimidating.”[97] The USA could adapt this model to the demands of its legal system and circumscribe criminalization to “hostile or intimidating” catcalls because “humiliating” ones would probably be part of protected speech in the USA. And, since catcalls of a more physical nature are not constitutionally protected, the USA could enforce comprehensive regulations of catcalling at the federal level.

My second conclusion is that sexism, and not freedom of speech, will probably be the major obstacle to criminalizing catcalls at the federal level. Moreover, even if catcalls were criminalized, enforcement of this crime could be minimal. Data from Belgium, where street harassment has been a crime since 2014, show that few women report it and, thus, “around 94% of these incidents go unreported.” The main reasons are either women have normalized catcalls or know the police are not going to take them seriously. [98]Similarly, in the USA (less than 8%) and Spain pre-enforcement of the 2022 Law (less than 3%); and for the same reasons.[99]

- Relevant Recommendations

I make three relevant recommendations based on catcall data and our society’s pervasive sexism. One provides a legal basis for criminalizing catcalls and the other two help reduce the negative effects of catcalls but could also contribute to criminalizing them. (1) Organizing political campaigns using the right to petition of the First Amendment to the US Constitution to convince our representatives in Washington DC to adopt a robust framework that advances gender equality, including identifying catcalls with VAW. To that end, members of Congress of the US, and state representatives should ratify the ERA, written more than a century ago (Bleiweis, 29 January 2020)[4]; and the Senate of the US should ratify the CEDAW and other core human rights treaties like the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child, the 1990 Convention on the Rights of Migrant Workers and their Families, and the 2006 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities;[100]thus, facilitating an intersectional approach.

(2) Implementing gender mainstreaming across the board but especially among law enforcement personnel—from police officers to judges and prosecutors—will facilitate accountability for catcalls. Adding a woman’s perspective is necessary to overcome the constraints imposed by the white man standard that most institutions adopt (Stop Street Harassment).[6] This standard facilitates the dismissal of women’s concerns about catcalling because men are rarely catcalled and, if they are, rarely feel threatened as women do. For example, if gender mainstreaming were the norm, almost everybody would understand why women feel objectively threatened by catcalls and why women and men walk differently at night. First, more than 60% of American women are afraid for their security when walking alone at night but only 26% of men are worried about an attack. And second, men who feel threatened will rarely think of rape.[101]

(3) Familiarizing oneself and disseminating the “Five D’s Methodology” to “StandUp to Sexual Harassment” developed by Right to Be (known before as Hollerback!) and promoted by L’Oréal Paris since 8 March 2020.[102] The “Five D’s” are Distract, Delegate, Document, Delay, and Direct. When documenting, it is necessary to check that the victim is OK and, after the incident, to ask the victim whether it is OK to make any documentation public. Right to Be added “Documentation” and “Direct” to Green Dot’s “3 D’s Methodology”.[103] Green Dot is a partner of “the Department of Justice Office on Violence Against Women (OVW) Campus Program since 2010. … to develop a training program that supports campuses across the country in … a primary prevention strategy that addresses sexual assault, dating/domestic violence, and stalking;” OVW does not recognize street harassment as VAW.[104] The “Five D‘s Methodology” promotes interventions that do not escalate the existing conflict and are expected to be used if they do not put anyone at risk of further harm.

About the author: M. Victoria Pérez-Ríos, PhD, JD teaches international human rights and comparative criminal justice systems as a Substitute Assistant Professor at the Political Science Department and the International Crime and Justice MA Program of John Jay College, and taught American government at LaGuardia CC.

- Congress Research Service. (n.d.). Fourteenth Amendment. Constitution Annotated. Retrieved on May 24, 2024, from https://constitution.congress.gov/constitution/amendment-14/. ↵

- Evans, L. (2013, October 8/Modified, October 9). Woman Sues NYC after Arrest for Going Topless in Brooklyn Park. The Gothamist. Retrieved on May 11, 2024, from https://gothamist.com/news/woman-sues-nyc-after-arrest-for-going-topless-in-brooklyn-park. ↵

- The People &C., Respondent, v. Ramona Santorelli and Mary Lou Schloss, Appellants, Et Al., Defendants. (1992, July 7). 80 N.Y.2d 875, 600 N.E.2d 232, 587 N.Y.S.2d 601 (1992). Cornell Law. Retrieved May 11, 2024, from https://www.law.cornell.edu/nyctap/I92_0160.htm. ↵

- UN Women. (2021, October 6). What Does Gender Equality Look Like Today? Retrieved on May 24, 2024, from https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2021/10/feature-what-does-gender-equality-look-like-today ↵

- World Population Review. (2024). Countries with Freedom of Speech 2024. Retrieved on May 25, 2024, from Countries with Freedom of Speech 2024 (worldpopulationreview.com) ↵

- World Economic Forum. (2023, June). Global Gender Gap Index Report 2023. Retrieved on May 24, 2024, from https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2023.pdf. ↵

- Fileborn, B. & O’Neill, T. (2023, January). From ‘Ghettoization’ to a Field of Its Own: A Comprehensive Review of Street Harassment Research. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse (TVA), Vol. 24(1), 125-38. Retrieved on March 20, 2024, from https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838021 ↵

- Di Gennaro, K. & Ritschel, C. (2019). Blurred Lines: The Relationship Between Catcalls and Compliments. Women's Studies International Forum Vol. 75. Retrieved on May 23, 2024, from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2019.102239. ↵

- O’Leary, C. (2016). Catcalling as a ‘Double-Edged Sword:’ Midwestern Women, Their Experiences, and the Implications of Men's Catcalling Behaviors. Theses and Dissertations. Retrieved on June 2, 2024, from https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1534&context=etd ↵

- Andrews, D. & Janoski, S. (2024, March 19). Heartbreaking Photos Emerge of NYC Twins Stabbed by Madman as Friends Mourn Sister Who Died. New York Post. Retrieved on April 17, 2024, from .https://nypost.com/2024/03/19/us-news/heartbreaking-photos-emerge-of-nyc-twins-stabbed-by-madman-as-friends-mourn-sister-who-died/ ↵

- Angermann, M. (2022, March 17). What is Catcalling and What You Can Do About it. Utopia.org. Retrieved on May 12, 2024, from https://utopia.org/guide/what-is-catcalling-and-what-you-can-do-about-it/ ↵

- RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network). (n.d.). What is Street Harassment. Retrieved on May 20, 2024, from https://www.rainn.org/articles/street-harassment ↵

- Di Gennaro, K. & Ritschel, C. (2019). Blurred Lines: The Relationship Between Catcalls and Compliments. Women's Studies International Forum Vol. 75. Retrieved on May 23, 2024, from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2019.102239 ↵

- NYC Street Harassment Prevention Advisory Board. (2023). End Street Harassment: A NYC Resource Guide. Last Retrieved on May 11, 2024, from https://www.nyc.gov/assets/ocdv/downloads/pdf/Stop_street_harassment_guide_TAGGED_Final.pdf ↵

- Smith, S. G., Zhang, X., Basile, K. C., Merrick, M. T., Wang, J., Kresnow, M., & Chen, J. (2018). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2015 Data Brief – Updated Release. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved on June 6, 2024, from https://www.nsvrc.org/sites/default/files/2021-04/2015data-brief508.pdf ↵

- Meyer, E. H. (2017, November 22). My Daughter Got Her First Catcall, And I Didn’t Know What to Tell Her. The Washington Post. Retrieved on May 12, 2024, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/parenting/wp/2017/11/22/my-daughter-got-her-first-catcall-and-i-didnt-know-what-to-tell-her/ ↵

- Hoff, V. D. (2015, May 29). Most 17-Year-Olds Have Already Been Catcalled: 84 Percent, To Be Exact. Elle.com. Retrieved on May 12, 2024, from https://www.elle.com/culture/career-politics/news/a28608/young-women-catcalling-problem/ ↵

- UN Women. (2018). Fourth UN Women Safe Cities and Safe Public Spaces Global Leaders’ Forum: Proceedings Report. Shaw Conference Centre, Edmonton, Alberta, October 2018. Retrieved on May 11, 2024, from https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Headquarters/Attachments/Sections/Library/Publications/2018/Fourth-UN-Women-Global-Forum-2018-Report-en.pdf ↵

- Plan Internacional. (June 2021). Safer Cities for Girls: Un análisis del acoso callejero en las ciudades de Barcelona, Madrid y Sevilla. Retrieved on May 29, 2014, from https://plan-international.es/files_informes/Safer_Cities_for%20Girls_Analisis_del_acoso_callejero_Barcelona_Madrid_Sevilla.pdf. ↵

- Moore, P. (2014, August 15). Catcalling: Never OK and Not a Compliment. YouGov.org. Retrieved on May 19, 2024, from https://today.yougov.com/society/articles/10126-catcalling?_gl=1*1ica9lv*_up*MQ..*_ga*MTU1ODA2MTA4OS4xNzE2MTE5NTA5*_ga_X9VN3LD3NE*MTcxNjExOTUwNi4xLjAuMTcxNjExOTUxNy4wLjAuMA ↵

- Moore, P. (2014, August 15). Catcalling: Never OK and Not a Compliment. YouGov.org. Retrieved on May 19, 2024, from https://today.yougov.com/society/articles/10126-catcalling?_gl=1*1ica9lv*_up*MQ..*_ga*MTU1ODA2MTA4OS4xNzE2MTE5NTA5*_ga_X9VN3LD3NE*MTcxNjExOTUwNi4xLjAuMTcxNjExOTUxNy4wLjAuMA ↵

- United Nations Development Programme. (2023). Gender Social Norms Index (GSNI): Breaking Down Gender Biases: Shifting Social Norms Towards Gender Equality. Retrieved on May 24, 2024, from https://hdr.undp.org/content/2023-gender-social-norms-index-gsni#/indicies/GSNI. ↵

- My Notes from Online Workshop (2024, January 18). Hate Crimes and Hate Speech: Understanding Legal and Policy Issues. John Jay College of Criminal Justice, CUNY ↵

- Global Platform for the Right to the City. (n.d.). Retrieved on May 19, 2020, from https://www.right2city.org/the-right-to-the-city/. ↵

- Ipsos. (2021). Enquête internationale sur le harcèlement sexuel dans l’espace public. Sponsored by L’Oréal Paris. Retrieved on May 27, 2024, from https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2021-03/ipsos_global_report_8_mars.pdf ↵

- Stop Street Harassment. (2019, April 30). Measuring #MeToo: A National Study on Sexual Harassment and Assault. UCSD Center On Gender Equity and Health. Retrieved on May 25, 2024, from https://stopstreetharassment.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/2019-MeToo-National-Sexual-Harassment-and-Assault-Report.pdf ↵

- Fileborn, B. & O’Neill, T. (2023, January). From ‘Ghettoization’ to a Field of Its Own: A Comprehensive Review of Street Harassment Research. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse (TVA), Vol. 24(1), 125-38. Retrieved on March 20, 2024, from https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380211021608 ↵

- Reichard, R. (2014, May 12). When Fear of Harassment Curbs Recovery from an Eating Disorder. The New York Times, blog. Retrieved on May 19, 2024, from https://archive.nytimes.com/cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/05/12/when-fear-of-harassment-curbs-recovery-from-an-eating-disorder/ ↵

- Loughnan, S., Baldissarri, C., Spaccatini, F. & Elder, L. (2017). Internalizing Objectification: Objectified Individuals See Themselves as Less Warm, Competent, Moral, and Human. British Journal of Social Psychology Vol. 56,.https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12188 ↵

- DelGreco, M. & Christensen, J. (2020). Effects of Street Harassment on Anxiety, Depression, and Sleep Quality of College Women. Sex Roles, Vol. 82, 473–481. Retrieved on May 19, 2024, from https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-01064-6 ↵

- Reichard, R. (2014, May 12). When Fear of Harassment Curbs Recovery from an Eating Disorder. The New York Times, blog. Retrieved on May 19, 2024, from https://archive.nytimes.com/cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/05/12/when-fear-of-harassment-curbs-recovery-from-an-eating-disorder/ ↵

- Carretta, R.F. & Szymanski, D.M.. (2020). Stranger Harassment and PTSD Symptoms: Roles of Self-Blame, Shame, Fear, Feminine Norms, and Feminism. Sex Roles Vol. 82, 525–540. Retrieved on June 1, 2024, from https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-01073-5. ↵

- Stop Street Harassment. (n.d.). Why Stopping Street Harassment Matters. Retrieved on May 20, 2024, from https://stopstreetharassment.org/about/what-is-street-harassment/why-stopping-street-harassment-matters/ ↵

- Stop Street Harassment. (n.d.). Why Stopping Street Harassment Matters. Retrieved on May 20, 2024, from https://stopstreetharassment.org/about/what-is-street-harassment/why-stopping-street-harassment-matters/ ↵

- ©M. Victoria Pérez-Ríos, PhD ↵

- Horton, A. (2019, November 27). A Woman Ignored a Man’s Catcalls — So He Chased Her Down and Killed Her, Prosecutors Say. The Washington Post. Retrieved on May 19, 2024, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/crime-law/2019/11/27/woman-ignored-mans-catcalls-so-he-chased-her-down-killed-her-prosecutors-say/ ↵

- Andrews, D. & Janoski S. (2024, March 19). Heartbreaking Photos Emerge of NYC Twins Stabbed by Madman as Friends Mourn Sister Who Died. New York Post. Retrieved on April 17, 2024, from https://nypost.com/2024/03/19/us-news/heartbreaking-photos-emerge-of-nyc-twins-stabbed-by-madman-as-friends-mourn-sister-who-died/ ↵

- Donaghue, E. (Updated: January 27, 2016). Docs: Woman Shot Dead After Rejecting Man's Advances at Bar. CBS News. Retrieved on May 20, 2024, from https://www.cbsnews.com/news/janese-jackson-talton-shot-dead-after-rejecting-mans-advances-at-bar-documents-say/ ↵

- Celona, L., Moore, T., & Cohen, S. (2016, 6 September). Student Killed at J’ouvert Wanted Man to Stop Grinding on Her: Cops. The New York Post. Retrieved on May 23, 2024, from https://nypost.com/2016/09/06/student-killed-at-jouvert-wanted-man-to-stop-grinding-on-her-cops/ ↵

- Abbey-Lambertz, K. (2014, November 13 /Updated 2017, December 6). Murder Charges for Man Who Allegedly Killed Woman After She Rejected Him. The Hufftington Press. Retrieved on May 19, 2024, from https://www.huffpost.com/entry/mary-spears-mark-dorch-detroit_n_6151152 ↵

- Rodriguez, M. & Schmadeke, S. (2014, March 21/Updated 2021, August 25). Father Dies Shielding Daughter, 15: ‘I’m Going to Make Him Proud.’ Chicago Tribune. Retrieved on May 23, 2024, from https://www.chicagotribune.com/2014/03/21/father-dies-shielding-daughter-15-im-going-to-make-him-proud/ ↵

- Kenney, T. (Updated, 2021, April 20). Catcaller Shoots Woman After She Ignores His ‘Belligerent’ Advances, Georgia Cops Say. The Telegraph. Retrieved on May 19, 2024, from https://www.macon.com/news/nation-world/national/article250812979.html#storylink=cpy ↵

- US Census Bureau. (2021, February 3). Census Bureau Releases Census of Governments Infographic. Press Release Number CB21-TPS.11. Retrieved on May 25, 2024, from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2021/governments-infographic.html ↵

- España Mi País. (n.d.). ¿Cuántas comunidades autónomas y provincias tiene España? Retrieved on May 25, 2024, from https://www.espanamipais.com/comunidades-autonomas-y-provincias-de-espana ↵

- United Nations Development Programme. (2023). Gender Social Norms Index (GSNI): Breaking Down Gender Biases: Shifting Social Norms Towards Gender Equality. Retrieved on May 24, 2024, from https://hdr.undp.org/content/2023-gender-social-norms-index-gsni#/indicies/GSNI ↵

- Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado. (2024, February 17). Constitución española: texto consolidado. Retrieved on March 25, 2024 from https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-1978-31229 ↵

- González-Casanova González, A. (2021, April). Comparación entre el Estado autonómico ↵

- Stop Street Harassment. (2019, April 30). Measuring #MeToo: A National Study on Sexual Harassment and Assault. UCSD Center On Gender Equity and Health. Retrieved on May 25, 2024, from https://stopstreetharassment.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/2019-MeToo-National-Sexual-Harassment-and-Assault-Report.pdf ↵

- ILR School and Hollaback! (2015, April 17). Street Harassment Statistics. Retrieved on May 22, 2024, from Street Harassment Statistics | The ILR School (cornell.edu) ↵

- ILR School and Hollaback! (2015, April 17). Street Harassment Statistics. Retrieved on May 22, 2024, from Street Harassment Statistics | The ILR School (cornell.edu); and Stop Street Harassment (SSH). (2019, April 30). Measuring #MeToo: A National Study on Sexual Harassment and Assault. UCSD Center On Gender Equity and Health. Retrieved on May 25, 2024, from https://stopstreetharassment.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/2019-MeToo-National-Sexual-Harassment-and-Assault-Report.pdf. Table based on these two sources. NORC was once known as the National Opinion Research Center ↵

- Stop Street Harassment. (circa 2019, May). Street Harassment and Age. Retrieved on May 22, 2024, from https://stopstreetharassment.org/our-work/nationalstudy/shage/ ↵

- Congress Research Service. (n.d.). Tenth Amendment. Constitution Annotated. Retrieved on June 2, 2024, from https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/essay/amdt10-2/ALDE_00013620/ ↵

- Berman v. Parker, 348 U.S. 26 (1954). Justia.com. Retrieved on May 22, 2024, from https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/348/26/ ↵

- Berman v. Parker, 348 U.S. 26 (1954). Justia.com. Retrieved on May 22, 2024, from https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/348/26/ ↵

- Beaumont, E. (January 1, 2009/last updated on February 18, 2024). Gitlow v. New York (1925). Free Speech Center at Middle Tennessee State University. Retrieved on May 25, 2024, from https://firstamendment.mtsu.edu/article/gitlow-v-new-york/. ↵

- Congress Research Service. (n. d.). Fourteenth Amendment. Constitution Annotated. Retrieved on May 24, 2024, from https://constitution.congress.gov/constitution/am ↵

- Gitlow v. New York, 268 U.S. 652. (1925). Justia. Retrieved on May 25, 2024, from https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/268/652/#tab-opinion-1930993 ↵

- Brinlee, M. (2018, August 2). Catcalling Laws Differ Depending on Where You Are in The US — Here's What They Entail. Bustle. Retrieved on May 12, 2024, from https://www.bustle.com/p/laws-against-catcalling-in-the-us-are-kind-of-a-mess-heres-what-they-entail-9983984 ↵

- The New York State Senate. (2023, March 10). Legislation: Consolidated Laws of New York, Chapter 40: Penal. Retrieved on May 26, 2024, from https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/laws/PEN ↵

- The New York State Senate. (2023, March 10). Legislation: Consolidated Laws of New York, Chapter 40: Penal. Retrieved on May 26, 2024, from https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/laws/PEN ↵

- The New York State Senate. (2023, March 10). Legislation: Consolidated Laws of New York, Chapter 40: Penal. Retrieved on May 26, 2024, from https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/laws/PEN ↵

- The New York State Senate. (2023, March 10). Legislation: Consolidated Laws of New York: Chapter 40: Penal. Retrieved on May 26, 2024, from https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/laws/PEN ↵

- The New York State Senate. (2023, March 10). Legislation: Consolidated Laws of New York, Chapter 40: Penal. Retrieved on May 26, 2024, from https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/laws/PEN ↵

- Stop Street Harassment. (n.d.). New York. Retrieved on May 22, 2024, from https://stopstreetharassment.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/SSH-KYR-NewYork.pdf ↵

- Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado. (2024, February 17). Constitución española: texto consolidado. Retrieved on March 25, 2024 from https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-1978-31229. ↵

- Subdirección General de Sensibilización, Prevención y Estudios de la Violencia de Género (Delegación del Gobierno contra la Violencia de Género). (2020). Macroencuesta de Violencia contra la Mujer 2019, Ch. 17, pp. 181-190. Ministerio de Igualdad. Retrieved on May 27, 2024, from https://violenciagenero.org/web/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/macroencuesta_2019_estudio_investigacion.pdf ↵

- Subdirección General de Sensibilización, Prevención y Estudios de la Violencia de Género (Delegación del Gobierno contra la Violencia de Género). (2020). Macroencuesta de Violencia contra la Mujer 2019, Ch. 17, pp. 181-190. Ministerio de Igualdad. Retrieved on May 27, 2024, from https://violenciagenero.org/web/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/macroencuesta_2019_estudio_investigacion.pdf ↵

- Subdirección General de Sensibilización, Prevención y Estudios de la Violencia de Género (Delegación del Gobierno contra la Violencia de Género). (2020). Macroencuesta de Violencia contra la Mujer 2019, Ch. 17, pp. 181-190. Ministerio de Igualdad. Retrieved on May 27, 2024, from https://violenciagenero.org/web/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/macroencuesta_2019_estudio_investigacion.pdf. ↵

- Subdirección General de Sensibilización, Prevención y Estudios de la Violencia de Género (Delegación del Gobierno contra la Violencia de Género). (2020). Macroencuesta de Violencia contra la Mujer 2019, Ch. 17, pp. 181-190. Ministerio de Igualdad. Retrieved on May 27, 2024, from https://violenciagenero.org/web/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/macroencuesta_2019_estudio_investigacion.pdf. ↵

- Subdirección General de Sensibilización, Prevención y Estudios de la Violencia de Género (Delegación del Gobierno contra la Violencia de Género). (2020). Macroencuesta de Violencia contra la Mujer 2019, Ch. 17, pp. 181-190. Ministerio de Igualdad. Retrieved on May 27, 2024, from https://violenciagenero.org/web/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/macroencuesta_2019_estudio_investigacion.pdf. ↵

- Plan International. (2021, June). Safer Cities for Girls: Un análisis del acoso callejero en las ciudades de Barcelona, Madrid y Sevilla. Retrieved on May 29, 2014, from https://plan-international.es/files_informes/Safer_Cities_for%20Girls_Analisis_del_acoso_callejero_Barcelona_Madrid_Sevilla.pdf. ↵

- Alonso, B. (2024, March 6). El impresionante porcentaje de españolas que han sentido acoso callejero alguna vez en su vida demuestra todo lo que queda por hacer. Elle.com. Retrieved on May 6, 2024, from https://www.elle.com/es/living/ocio-cultura/a60107808/acoso-callejero-mujeres-espanolas-informe/ ↵

- Sen, C. (2021, 26 julio). Acoso callejero, ninguna chica a salvo. La Vanguardia. Retrieved on June 10, 2024, from https://www.lavanguardia.com/vida/20210726/7624233/acoso-callejero-ninguna-chica-salvo.html. ↵

- Alonso, B. (2024, March 6). El impresionante porcentaje de españolas que han sentido acoso callejero alguna vez en su vida demuestra todo lo que queda por hacer. Elle.com. Retrieved on May 6, 2024, from https://www.elle.com/es/living/ocio-cultura/a60107808/acoso-callejero-mujeres-espanolas-informe/; Plan International. (2021, June). Safer Cities for Girls: Un análisis del acoso callejero en las ciudades de Barcelona, Madrid y Sevilla, pp. 6 and 7. Retrieved on May 29, 2014, from https://plan-international.es/files_informesSafer_Cities_for%20Girls_Analisis_del_acoso_callejero_Barcelona_Madrid_Sevilla.pdf; and Subdirección General de Sensibilización, Prevención y Estudios de la Violencia de Género (Delegación del Gobierno contra la Violencia de Género). (2020). Macroencuesta de Violencia contra la Mujer. 2019. Ministerio de Igualdad. Retrieved on May 27, 2024, from https://violenciagenero.org/web/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/macroencuesta_2019_estudio_investigacion.pdf ↵

- Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado. (21 March 1984). Instrumento de Ratificación de 16 de diciembre de 1983 de la Convención sobre la eliminación de todas las formas de discriminación contra la mujer, hecha en Nueva York el 18 de diciembre de 1979. BOE-A-1984-6749, pp. 7715 to 7720. Retrieved on June 3, 2024, from https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-1984-67497 ↵

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). (1979). https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-elimination-all-forms-discrimination-against-women ↵

- Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado. (2014, June 6). Instrumento de ratificación del Convenio del Consejo de Europa sobre prevención y lucha contra la violencia contra la mujer y la violencia doméstica, hecho en Estambul el 11 de mayo de 2011. BOE-A-2014-5947, pp. 42946 to 42976. Retrieved on June 3, 2024, from https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2014-5947. ↵

- Council of Europe. (2011, May 11). Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence. Council of Europe Treaty Series No. 211. Retrieved on May 11, 2024, from https://rm.coe.int/168008482e ↵

- Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE). (2022, September 7). Ley Orgánica 10/2022, de 6 de septiembre, de garantía integral de la libertad sexual. BOE-A-2022-14630, pp.124199 to 124269. Retrieved on June 4, 2024, from https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2022-14630 ↵

- Sánchez Benítez, C. (2023, June). Tratamiento jurídico-penal del acoso en España: Especial referencia a las Leyes Orgánicas 4/2022, de 12 de abril y 10/2022, de 6 de septiembre. Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado: Legislación, pp. 157-186. Retrieved on March 20, 2024, from https://www.boe.es/biblioteca_juridica/abrir_pdf.php?id=PUB-DP-2023-293 ↵

- Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE). (circa 2023). Código Penal Actualizado. Última modificación, 28 April 2023. Retrieved on June 5, 2024, from https://www.boe.es/biblioteca_juridica/abrir_pdf.php?id=PUB-DP-2023-118 ↵

- Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE). (circa 2023). Código Penal Actualizado. Última modificación, 28 April 2023. Retrieved on June 5, 2024, from https://www.boe.es/biblioteca_juridica/abrir_pdf.php?id=PUB-DP-2023-118 ↵

- Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE). (circa 2023). Código Penal Actualizado. Última modificación, 28 April 2023. Retrieved on June 5, 2024, from https://www.boe.es/biblioteca_juridica/abrir_pdf.php?id=PUB-DP-2023-118 ↵

- Council of Europe. (2011, May 11). Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence. Council of Europe Treaty Series No. 211. Retrieved on May 11, 2024, from https://rm.coe.int/168008482e ↵

- Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE). (circa 2023). Código Penal Actualizado. Última modificación, 28 April 2023. Retrieved on June 5, 2024, from https://www.boe.es/biblioteca_juridica/abrir_pdf.php?id=PUB-DP-2023-118 ↵

- Rosselló, G. (2022, May 26). Vox, sobre los piropos por la calle: ‘Es una pena que se pierdan esas muestras de admiración e ingenio popular.’ Última Hora. Retrieved on June 5, 2024, from https://www.ultimahora.es/noticias/nacional/2022/05/26/1738939/vox-sobre-piropos-por-calle-pena-pierdan-esas-muestras-admiracion-ingenio-popular.html ↵