105 Human Modifications of Coastal Processes

The anthropogenic (human-influenced) changes to coastal environments may take many forms: creation or stabilization of inlets, beach nourishment and sediment bypassing, creation of dunes for property protection, dredging of waterways for shipping and commerce, and introduction of hard structures such as jetties, groins, and seawalls. These modifications change coastal features and have far-reaching effects on coastal processes and ecosystems. An understanding of how human changes alter shoreline environments and park resources is vital for the protection and preservation of coastal areas.

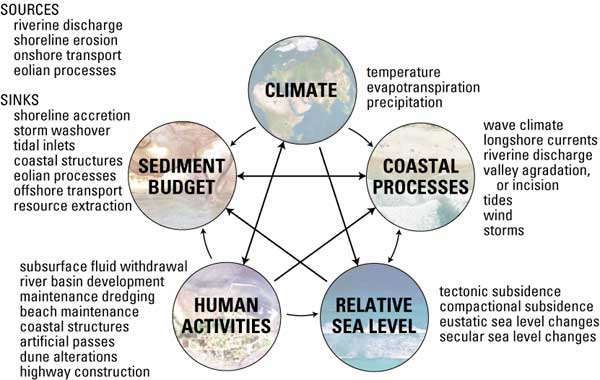

Variations in sea levels are natural responses to climate change, movements of the sea floor and other Earth processes. Human actions, including drainage of wetlands, withdrawal of groundwater (which eventually flows to the sea), and deforestation (which reduces terrestrial water-storage capacity), may also contribute to global rise in sea level. Additionally, human-induced climate change, primarily through the burning of fossil fuels, is also of importance. Local changes may be caused by large engineering works nearby, such as river channeling or dam construction that influence sediment delivery and deposition in deltaic areas. The diagram below shows complex interactions between five factors affecting land loss: climate, sediment budget, human activities, relative sea-level and coastal processes.

Sand mining, especially in vicinity of the coastline is one of the critical activities around the world that causes coastal erosion.

As Myanmar farmers lose their land, sand mining for Singapore is blamed

There are two methods of minimizing coastal erosion: hard stabilization (creating structures) and soft stabilization (adding sand to the beach).

Soft Stabilization

Beach Nourishment

Beach nourishment is the process of placing additional sediment on a beach. This material is obtained from another source that either lies inland or is dredged offshore. Nourishment entails the removal of sediment from “borrow sites,” and the subsequent transport of the sediment to beach areas. Borrow sites may alter sediment transport, hydrodynamic patterns, marine ecosystems, and sediment transport, such as creating erosional “hot spots” on adjacent shorelines.

Subaqueous nourishment is an alternative form of replenishment. The creation of offshore berms (mounds) may be utilized for the subsequent landward migration of sediments, often leading to sediment accretion on adjacent beaches. Although still a fairly new replenishment method, and not documented as fully effective, subaqueous nourishment may be substituted on account of cost limitations or biotic complications (e.g., migration and preserving endangered species) resulting from direct beach nourishment.

Often, beach nourishment is needed to counteract the effects of the hard-structure stabilization of coastlines. These structures (e.g., jetties, groins, and seawalls) typically increase downdrift erosion rates, promoting a need for continued coastal modifications through nourishment. The need for beach nourishment after human alteration is quite evident at Assateague Island National Seashore (Maryland). In the mid-1930s, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers established a jetty system to stabilize the Ocean City inlet. While sediment transported by north-to-south longshore currents increased sediment accretion updrift of the jetties at Ocean City, excessive erosion and barrier island migration have occurred on the island to the south of the jetties. That is, Assateague Island has migrated westward more than 1,148 feet (350 m) since 1933! The deterrence of longshore sediment transport to Assateague Island National Park has had numerous detrimental impacts on biological, geologic, and cultural resources. Both short-term and long-term beach nourishment plans are in place to mitigate the destructive effects of jetty placement.

For more information check out this web site:

- Report by the U.S. Geological Survey on coastal conflicts that highlights Ocean City jetty construction and Assateague Island migration

Beach grading

Beach grading (or bulldozing) is the process of reshaping beach and dune landforms with heavy machinery. Usually a layer of sand from the lower beach is moved to the upper beach. Beach grading creates dunes, which are used to give property owners some security from beach erosion, severe storms, and winter wash over events. During the summers, the created sandbanks may be bulldozed flat, providing water views to property owners. However, the effects of beach grading on coastal environments are little known, and this procedure may be harmful to coastal biota and habitats. Proponents claim that beach grading is a time and cost-effective method to ensure shoreline protection, while opponents state that this method may be the most ecologically destructive form of coastal manipulation to date.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Soft Shoreline Stabilization

Alternative soft stabilization approaches can offer many benefits over typical hard stabilization structures. Often these approaches are referred to as living shorelines, because they offer added ecological benefits. Some of the benefits of soft stabilization approaches include:

- Maintaining natural shoreline dynamics and healthy sand movement across a coastal cell

- Trapping sand to rebuild eroded shorelines or maintain current shoreline form

- Providing or enhancing important shoreline habitat

- Reducing wave energy impacts at or seaward of the shoreline

- Absorbing storm surge and flood waters

- Filtering nutrients and other pollutants from the water

- Maintaining beach and intertidal areas that offer public access opportunities for wading, fishing and walking

- Reducing the costs of stabilization from bulkheads, rip rap, and other hard structural approaches

- Creating a carbon sink and thereby helping mitigate climate change

While there are many benefits associated with living shorelines, they are not appropriate for all geomorphic environments. Drawbacks for living shorelines include:

- Not being appropriate for high energy environments

- Not being as effective where much of the shoreline is already hardened

- Being more difficult to design and install than more traditional hard structural approaches

- Having limited information available on the effectiveness of living shorelines for different types of shorelines, energy regimes, and storm conditions

Source:https://serc.carleton.edu/integrate/teaching_materials/coastlines/student_materials/1073

Hard Stabilization

Special structures are often placed in marine environments to counteract erosion in sediment-deficient areas, or to deter accretion in sediment-rich areas such as inlets. Unfortunately, these anthropogenic modifications may accelerate erosion in adjacent down drift areas, increasing the need for additional hard structures. They tend to protect property but not the beach. With time however, when beach disappears, these structures fall down and need to be replaced. The creation of new hard structures is currently banned in many states, or strongly discouraged as coastal management practice.

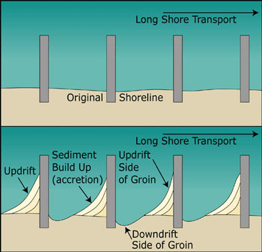

Groins (originally groynes) are shore-perpendicular structures, used to maintain up drift beaches or to restrict long shore sediment transport. Permeable groins are becoming popular, and may negate some of the negative effects of impermeable groins. Another type of shore-perpendicular hard structure are jetties, which are normally placed adjacent to tidal inlets to control inlet migration and to minimize sediment deposition within the inlet.

Figures below show groins in Sitges, Catalonia, Spain and timber groines in Bournemouth, England

Shore parallel structures include seawalls, bulkheads, and revetments. These structures are designed to protect coastal property. Development permits are relatively easy to obtain in many states because seawalls may be built above the high-water mark on private property, and they are relatively inexpensive, compared to beach nourishment. Ironically, seawalls usually accelerate erosion on beaches they are intended to protect. Wave energy is reflected off seawalls, increasing erosion in front of them. The placement of a seawall will decrease the sediment supply near seawalls, increasing erosion on adjacent beaches. In many areas, beaches have completely eroded and disappeared on account of seawalls.

Figure below shows an example of a modern seawall in Ventnor on the Isle of Wight Source:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seawall Another example of seawall is a structure, made of rocks in Paravur near Kollam city in India.

Source:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seawall Another example of seawall is a structure, made of rocks in Paravur near Kollam city in India.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seawall

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seawall

Groins

Groins interact with the longshore drift by trapping sand. The diagram below shows original shoreline and existing longshore drift. Groins trap sediments on one side (updrift) and cause erosion on another side (downdrift). Therefore, if we start building one groin we need to construct much more to avoid eventual erosion downdrift. This is a problem with groin implementation.

Source:https://www.nccoast.org/protect-the-coast/advocate/terminal-groins/

Source:https://www.nccoast.org/protect-the-coast/advocate/terminal-groins/

Figure in this story: https://www.southernenvironment.org/news-and-press/news-feed/selc-partners-appeal-georgia-courts-decision-allowing-construction-of-sea-i shows an aerial view of Sea Island’s (Fulton County, Georgia, USA) existing groin shows a visible increase in shoreline erosion south of the structure. The eroded area includes key habitat for endangered and threatened sea turtles and nesting areas for the threatened loggerhead sea turtle. (© GoogleEarth)

Other anthropogenic structures that are used to stop or alter natural coastal changes include breakwaters, headlands, sills, and reefs. These structures are composed of either natural or artificial materials, and are designed to alter the effects of waves and slow coastline erosion and change. Submerged reefs and sills dampen wave energy and may create new habitat, which is significant for local fisheries. However, the long-term effects of these structures, on both physical and biological processes, are not understood and require thorough examination.

Coastal management includes integration of various methods to protect coastline from erosion and flooding. Below is a figure explaining five main ways to protect the shore.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coastal_management

The poor effectiveness of both, soft and hard stabilization was noticed even back in 1981 by more than 60 coastal scientists who signed famous Skidaway Conference paper (25-27 March, 1981, Savannah, Georgia).

“It is readily apparent from the numerous examples of submerged and stranded jetties, multiple seawalls, and groins now detached from the shoreline that many

stabilization projects have been failures. ” (p. 11)

“We are clearly at a point today when decisions relating to coastal erosion can call upon a vast reserve of research results and capabilities as well as innovative

technology. The fact that we continually fail to do so is absurd. The responsibility rests on the shoulders of shortsighted politicians, developers and coastal engineers

among others who, through ignorance, haste, or in response to political pressure, fail to utilize the results of available research reports, the tools and techniques

developed from coastal research and the talents of numerous highly qualified research scientists.” (p. 11)

“Many attempts at artificial stabilization should never have been undertaken in the first place. Many others should be stopped immediately and no new projects should be initiated until a solid, unbiased economic study is made and it is clearly determined who will benefit and who will suffer, what it will cost and who will initially and eventually pay for the project.” (p. 11)

“Traditionally, problems of shoreline erosion are “solved’ by the quickest and cheapest methods. But tnere are no quick and cheap solutions to “problems” that

are the result of long term processes. Managers have failed to consider the long term costs and the cost/benefit ratios involved. Past, present and future coastal

programs must be evaluated by using a combined scientific-economic yardstick.” (p. 12)

“This is a seemingly endless cycle of events which, due to a compounding of errors and poorly-thought-ou t decisions, becomes increasingly more expensive. By the time someone is willing to admit it wasn’t worth the initial expense even i f it had worked, the shoreline has been so highly developed that engineers, planners, politicians are totally locked into a program of continued commitment.” (p. 12)

Rebuild or retreat? The future of Louisiana’s coastline in jeopardy

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/louisiana-coastline-60-minutes-2020-12-22/

Echo of the Skidaway Position Paper: A Glimpse to The Current State of Rebuilding Beaches

Recent article in New Yorker highlights the history of the coastal management on New Jersey shore: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2013/07/22/the-beach-builders