73 Ocean Movement

Waves

Wind-generation of waves involves a transfer of energy from moving air to a water surface. Although a very familiar process, the way in which this occurs is still not fully understood (Summerfield 1991). The amount of energy exchanged depends mainly on velocity, duration, and fetch (the distance over which the wind blows, which has an important influence on wave height and period) of the wind.

The direction of wind influences fetch distance depending on the configuration of the coastline of the water bodies.

https://learn.m.weatherstem.com/modules/learn/lessons/94/09.html

Wave Elements:

Wave Motion

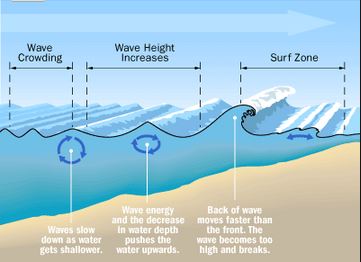

In the deep ocean, little forward motion of water in waves occurs because the wave form moves rather than the water. Motion is circular in open ocean. As waves move toward shallower water, however, their mode of movement changes dramatically. The seafloor starts to interfere with the oscillatory motion of waves where the water depth decreases to less than half that of the wave length. The orbit of individual water particles becomes less circular and more elliptical.

Forward movement of water now becomes important as the oscillatory (deep-ocean) waves are transformed into translatory waves. As the water depth becomes progressively more shallow, wave length and velocity decrease, wave height increases and consequently the wave steepens. Eventually the wave is over-steepened to the stage where it breaks as its crest crashes forward creating surf. The zone of active breaking waves is known as the surf zone. Once the wave form has been destroyed, the remaining water moves up the shore as swash and returns under the force of gravity as undertow.

Wave energy & motion:

Source:http://treasurebeachesreport.blogspot.com/2015/07/71615-report-water-metal-detecting.html Upon reaching the shore wave speed changes depending on the depth. This causes wave front to “bend”, creating so-called wave refraction.

Wave refraction causes redistribution of energy along the shore creating zones of divergence (energy dissipates) and convergence (energy concentrates).

See http://www.physicalgeography.net/fundamentals/10ac_2.html for more explanation.

Upon approaching the shore waves can plunge or spill. Figure below shows a plunging breaker that occur on steep underwater slopes.

Source: – http://www.nesdis.noaa.gov/news_archives/wod_2013.html Breaking waves are favorites for surfers. One of the most famous coasts in the world with high breaking waves is Portugal.

Source: – http://www.nesdis.noaa.gov/news_archives/wod_2013.html Breaking waves are favorites for surfers. One of the most famous coasts in the world with high breaking waves is Portugal.

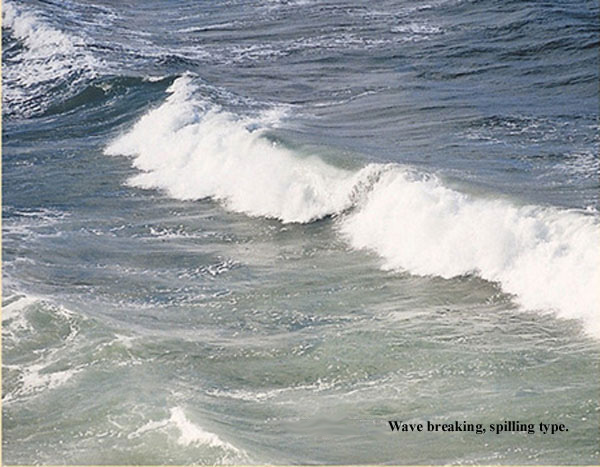

Figure below shows spilling breaker that occur on a gradual slope with slowly dissipating energy.

Source: http://geology.uprm.edu/MorelockSite/morelockonline/2-waves.htm

Source: http://geology.uprm.edu/MorelockSite/morelockonline/2-waves.htm

Tides

Tides result from the gravitational attraction exerted on ocean water by the Moon and the Sun. Because the Moon is closer to Earth, it has more than twice the gravitational effect of the distant Sun, despite the immense size and mass of the Sun.

The motions of Earth, Moon, and Sun with respect to one another produce semi-diurnal tides along most coasts in which there are two lows and two highs approximately every 24 hours.

Tides higher than normal, known as spring tides, occur every 14–17 days when the Sun and Moon are aligned. In between these periods, lower than normal—or neap tides—occur when the Sun and Moon are positioned at an angle of 90° with respect to Earth. Spring and neap tides involve deviations of about 20% above and below normal tidal range.

Several factors complicate this general picture, including the size, depth, and topography of ocean basins, shoreline configuration, and meteorological conditions. Much of the Pacific coast, for instance, experiences a regime of mixed tides in which highs and lows of each 24-hour period are of different magnitudes. Other coastlines, such as much of Antarctica, have diurnal tides with only one high and one low per 24 hours.

Although contrasts between tidal types are important in some coastal processes, of much greater overall geomorphic significance is tidal range. The most extreme ranges occur where coastal configuration and submarine topography induce an oscillation of water in phase with the tidal period. This effect is particularly pronounced in the Bay of Fundy, an inlet of the Atlantic Ocean in southeastern Canada, where the typical tidal range is more than 50 feet (16 m).

Figure 2. High tide and low tide at Alma, New Brunswick in the Bay of Fundy, 1972

Currents

The horizontal movement of water (or air) is called a current. Reflected, or turned back, by the beach slope, water from waves becomes undertow or cross-shore currents, flowing seaward. As cross-shore currents meet with incoming waves, some water spreads sideward and merges with other sideward-moving water. The combined waters form an elongated cell from which water flows seaward as a rip current, which extends to the so-called rip end, as much as half mile (0.80 km) offshore, where the water disperses in various directions. Rip currents disperse outside of the surf zone.

Meanwhile, some water from undertow and incoming waves flow sideward parallel to the shore as longshore currents. These are created in part by waves meeting the shore obliquely. Longshore currents can be very strong; they can transport sediments and people along the coast. In areas with offshore mounds of sand, known as sandbars, longshore currents are often very strong in the trough that separates the sandbar from the beach.

Longshore currents commonly feed into rip currents, mainly those on the downwind side.

Waves are often known as the “shakers” of the beach environment. The motions of waves in shallow water act to suspend sediment, while currents move or transport the sediments. Currents associated with tides can transport and erode sediment where flow velocities are high. This is usually confined to estuaries or other enclosed sections of coast that experience semi-diurnal tides with a high range.

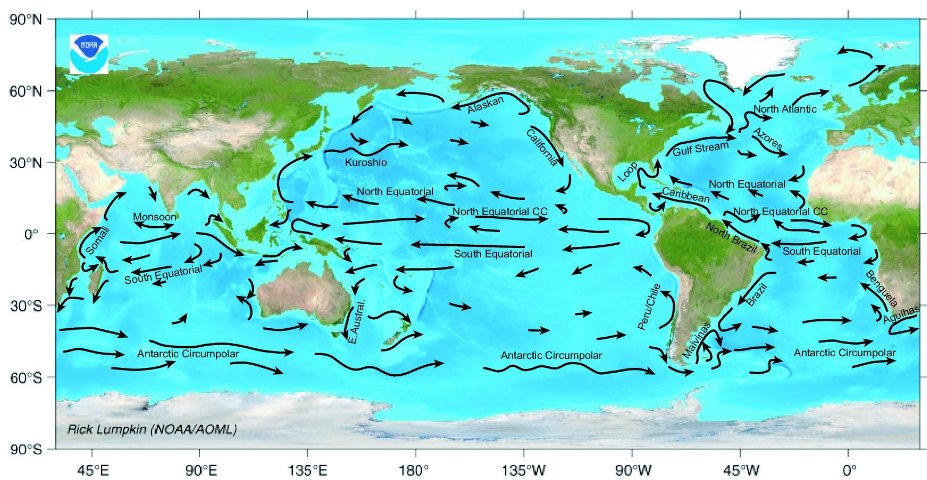

Ocean currents are produced by a number of forces acting upon the water, including wind, the Coriolis effect, temperature and salinity differences.

Ocean flows at surface and 2000 meters below sea level

Here is animation showing the movement of oceanic currents over long period of time: