30 Theory of Plate Tectonics

When the concept of seafloor spreading came along, scientists recognized that it was the mechanism to explain how continents could move around Earth’s surface.

Like the scientists before us, we will now merge the ideas of continental drift and seafloor spreading into the theory of plate tectonics.

Earth’s Tectonic Plates

In 1947, a team of scientists led by Maurice Ewing utilizing the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s research vessel Atlantis and an array of instruments, confirmed the existence of a rise in the central Atlantic Ocean, and found that the floor of the seabed beneath the layer of sediments consisted of basalt, not the granite which is the main constituent of continents. They also found that the oceanic crust was much thinner than continental crust. All these new findings raised important and intriguing questions.[5]

The second piece of evidence in support of continental drift came during the late 1950s and early 60s from data on the bathymetry of the deep ocean floors and the nature of the oceanic crust such as magnetic properties and, more generally, with the development of marine geology which gave evidence for the association of seafloor spreading along the mid-oceanic ridges and magnetic field reversals, published between 1959 and 1963 by Heezen, Dietz, Hess, Mason, Vine & Matthews, and Morley.[6]

Seafloor and continents move around on Earth’s surface, but what is actually moving? What portion of the Earth makes up the “plates” in plate tectonics? This question was also answered because of technology developed during war times – in this case, the Cold War. The plates are made up of the lithosphere.

During the 1950s and early 1960s, scientists set up seismograph networks to see if enemy nations were testing atomic bombs. These seismographs also recorded all of the earthquakes around the planet. These studies together with many other geophysical (e.g. gravimetric) and geological observations, showed how the oceanic crust could disappear into the mantle, providing the mechanism to balance the extension of the ocean basins with shortening along its margins.

All this evidence, both from the ocean floor and from the continental margins, made it clear around 1965 that continental drift was feasible and the theory of plate tectonics, which was defined in a series of papers between 1965 and 1967, was born, with all its extraordinary explanatory and predictive power. The theory revolutionized the Earth sciences, explaining a diverse range of geological phenomena and their implications in other studies such as paleogeography and paleobiology.

As it was observed early that although granite existed on continents, seafloor seemed to be composed of denser basalt, the prevailing concept during the first half of the twentieth century was that there were two types of crust, named “sial” (continental type crust) and “sima” (oceanic type crust). Furthermore, it was supposed that a static shell of strata was present under the continents. It therefore looked apparent that a layer of basalt (sial) underlies the continental rocks.

However, based on abnormalities in plumb line deflection by the Andes in Peru, Pierre Bouguer had deduced that less-dense mountains must have a downward projection into the denser layer underneath. The concept that mountains had “roots” was confirmed by George B. Airy a hundred years later, during study of Himalayan gravitation, and seismic studies detected corresponding density variations. Therefore, by the mid-1950s, the question remained unresolved as to whether mountain roots were clenched in surrounding basalt or were floating on it like an iceberg.

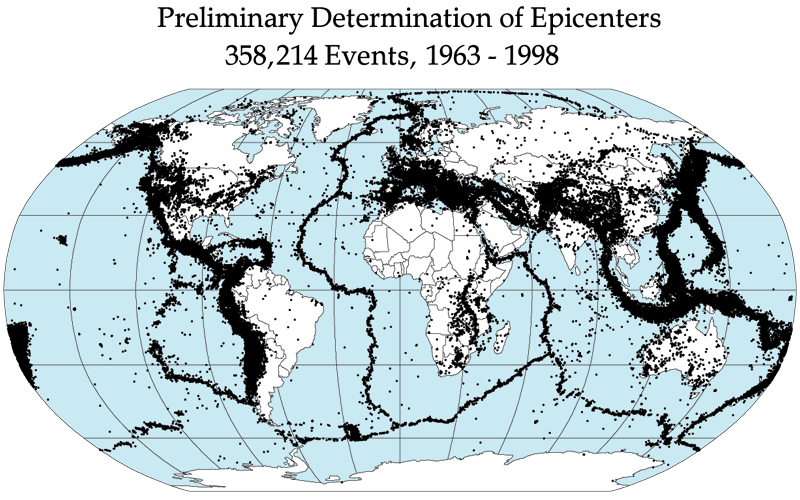

During the 20th century, improvements in and greater use of seismic instruments such as seismographs enabled scientists to learn that earthquakes tend to be concentrated in specific areas, most notably along the oceanic trenches and spreading ridges. By the late 1920s, seismologists were beginning to identify several prominent earthquake zones parallel to the trenches that typically were inclined 40–60° from the horizontal and extended several hundred kilometers into the Earth. These zones later became known as Wadati-Benioff zones, or simply Benioff zones, in honor of the seismologists who first recognized them, Kiyoo Wadati of Japan and Hugo Benioff of the United States.

Figure 1

Earthquake epicenters outline the plates. Mid-ocean ridges, trenches, and large faults mark the edges of the plates, and this is where earthquakes occur (figure 1 above).

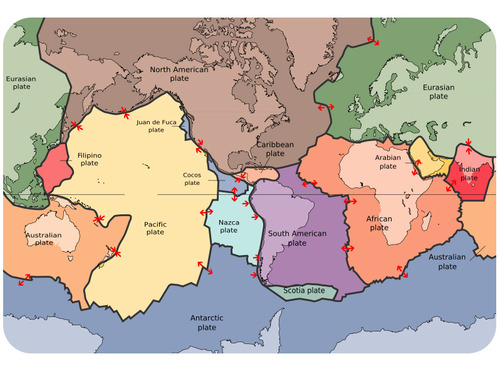

The lithosphere is divided into a dozen major and several minor plates (figure 2). The plates’ edges can be drawn by connecting the dots that mark earthquakes’ epicenters. A single plate can be made of all oceanic lithosphere or all continental lithosphere, but nearly all plates are made of a combination of both.

Movement of the plates over Earth’s surface is termed plate tectonics. Plates move at a rate of a few centimeters a year, about the same rate fingernails grow.

How Plates Move

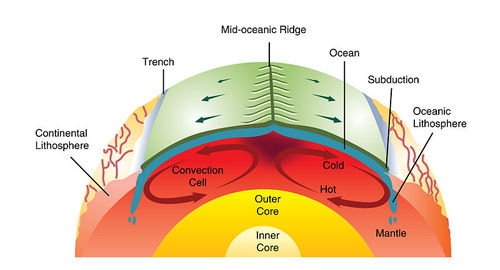

Figure 3. Mantle convection drives plate tectonics. Hot material rises at mid-ocean ridges and sinks at deep sea trenches, which keeps the plates moving along the Earth’s surface.

Figure 3. Mantle convection drives plate tectonics. Hot material rises at mid-ocean ridges and sinks at deep sea trenches, which keeps the plates moving along the Earth’s surface.

If seafloor spreading drives the plates, what drives seafloor spreading? Picture two convection cells side-by-side in the mantle, similar to the illustration in figure 3.

- Hot mantle from the two adjacent cells rises at the ridge axis, creating new ocean crust.

- The top limb of the convection cell moves horizontally away from the ridge crest, as does the new seafloor.

- The outer limbs of the convection cells plunge down into the deeper mantle, dragging oceanic crust as well. This takes place at the deep sea trenches.

- The material sinks to the core and moves horizontally.

- The material heats up and reaches the zone where it rises again.

Plate Boundaries

Plate boundaries are the edges where two plates meet. Most geologic activities, including volcanoes, earthquakes, and mountain building, take place at plate boundaries. How can two plates move relative to each other?

- Divergent plate boundaries: the two plates move away from each other.

- Convergent plate boundaries: the two plates move towards each other.

- Transform plate boundaries: the two plates slip past each other.

The type of plate boundary and the type of crust found on each side of the boundary determines what sort of geologic activity will be found there.

How the continents are moving?

Divergent Plate Boundaries

In 1947, a team of scientists led by Maurice Ewing utilizing the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s research vessel Atlantis and an array of instruments, confirmed the existence of a rise in the central Atlantic Ocean, and found that the floor of the seabed beneath the layer of sediments consisted of basalt, not the granite which is the main constituent of continents. They also found that the oceanic crust was much thinner than continental crust. All these new findings raised important and intriguing questions.[7]

The new data that had been collected on the ocean basins also showed particular characteristics regarding the bathymetry.

One of the major outcomes of these datasets was that all along the globe, a system of mid-oceanic ridges was detected. An important conclusion was that along this system, new ocean floor was being created, which led to the concept of the “Great Global Rift.” This was described in the crucial paper of Bruce Heezen (1960),[8] which would trigger a real revolution in thinking.

A profound consequence of seafloor spreading is that new crust was, and still is, being continually created along the oceanic ridges. Therefore, Heezen advocated the so-called “expanding Earth” hypothesis of S. Warren Carey. So, still the question remained: how can new crust be continuously added along the oceanic ridges without increasing the size of the Earth? In reality, this question had been solved already by numerous scientists during the forties and the fifties, like Arthur Holmes, Vening-Meinesz, Coates and many others: The crust in excess disappeared along what were called the oceanic trenches, where so-called “subduction” occurred.

Therefore, when various scientists during the early sixties started to reason on the data at their disposal regarding the ocean floor, the pieces of the theory quickly fell into place. Robert S. Dietz, a scientist with the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey first coined the term seafloor spreading.

Plates move apart at mid-ocean ridges where new seafloor forms.

Aliens of the Deep (2:38): View or the mid-oceanic ridge, spreading zone, divergent boundary

Þingvellir (sounds like Thingvelir) – Iceland (2:11): View of the mid-oceanic ridge appearing in Iceland

Diver in the Mid-Oceanic Rift (photo):

https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=308837438564265&set=a.132472856200725

Role of tectonic activities in the oceans in medicine:

See: https://www.whoi.edu/news-insights/content/finding-answers-in-the-ocean/

————————————————————————————————————–

STUDENT ACTIVITY: GOING TO EXPEDITION TO DISCOVER VOCLANIC ACTIVITY IN THE OCEAN!

HOW SCIENTISTS FIND VOLCANIC ACTIVITY (VENTS) ON THE SEA FLOOR?

Let’s go for the expedition with American Museum of Natural History:

https://www.amnh.org/education/resources/rfl/web/findavent/#/expedition

————————————————————————————————–

Between the two diverging plates is a rift valley. Lava flows at the surface cool rapidly to become basalt, but deeper in the crust, magma cools more slowly to form gabbro. So the entire ridge system is made up of igneous rock that is either extrusive or intrusive.

Earthquakes are common at mid-ocean ridges since the movement of magma and oceanic crust results in crustal shaking. The vast majority of mid-ocean ridges are located deep below the sea (figure 4).

Figure 4. (a) Iceland is the one location where the ridge is located on land: the Mid-Atlantic Ridge separates the North American and Eurasian plates; (b) The rift valley in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge on Iceland.

Figure 4. (a) Iceland is the one location where the ridge is located on land: the Mid-Atlantic Ridge separates the North American and Eurasian plates; (b) The rift valley in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge on Iceland.

Figure 5. The Arabian, Indian, and African plates are rifting apart, forming the Great Rift Valley in Africa. The Dead Sea fills the rift with seawater.

Can divergent plate boundaries occur within a continent? What is the result?

In continental rifting (figure 5), magma rises beneath the continent, causing it to become thinner, break, and ultimately split apart. New ocean crust erupts in the void, creating an ocean between continents.

Spreading: helping to identify ages of oceans

Spreading of the ocean floor results in creating new basalt layers. These rocks preserve information about changes in magnetic polarity.

The figure shows the spreading ridge about 5 million years ago (a), about 2 to 3 million years ago (b) and nowadays (c). Source: USGS

By matching magnetic reversal records from the ocean floor with the same records from continental rocks, already dated, scientists were able to estimate the age of the ocean floor.

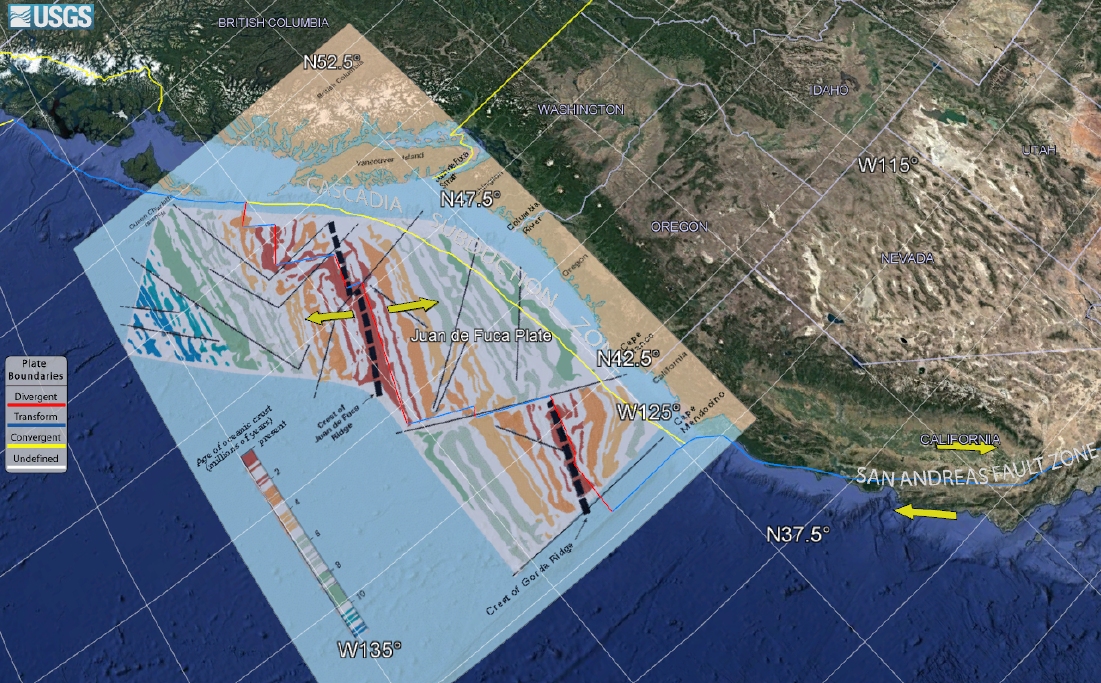

See below a figure with results of modern study of magnetic polarity in Juan de Fuca Plate:

Convergent Plate Boundaries

When two plates converge, the result depends on the type of lithosphere the plates are made of. No matter what, smashing two enormous slabs of lithosphere together results in magma generation and earthquakes.

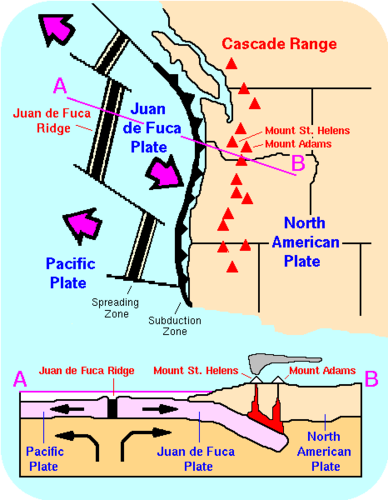

Ocean-Continent

When oceanic crust converges with continental crust, the denser oceanic plate plunges beneath the continental plate. This process, called subduction, occurs at the oceanic trenches (figure 6).

Figure 6. Subduction of an oceanic plate beneath a continental plate causes earthquakes and forms a line of volcanoes known as a continental arc.

The entire region is known as a subduction zone. Subduction zones have a lot of intense earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. The subducting plate causes melting in the mantle. The magma rises and erupts, creating volcanoes. These coastal volcanic mountains are found in a line above the subducting plate (figure 7). The volcanoes are known as a continental volcanic arc.

The movement of crust and magma causes earthquakes.

Look at this map of earthquake epicenters at subduction zones.

The volcanoes of northeastern California—Lassen Peak, Mount Shasta, and Medicine Lake volcano—along with the rest of the Cascade Mountains of the Pacific Northwest are the result of subduction of the Juan de Fuca plate beneath the North American plate (figure 8). The Juan de Fuca plate is created by seafloor spreading just offshore at the Juan de Fuca ridge.

If the magma at a continental arc is felsic, it may be too viscous (thick) to rise through the crust. The magma will cool slowly to form granite or granodiorite. These large bodies of intrusive igneous rocks are called batholiths, which may someday be uplifted to form a mountain range (figure 9).

Figure 9. The Sierra Nevada batholith cooled beneath a volcanic arc roughly 200 million years ago. The rock is well exposed here at Mount Whitney. Similar batholiths are likely forming beneath the Andes and Cascades today.

Figure 9. The Sierra Nevada batholith cooled beneath a volcanic arc roughly 200 million years ago. The rock is well exposed here at Mount Whitney. Similar batholiths are likely forming beneath the Andes and Cascades today.

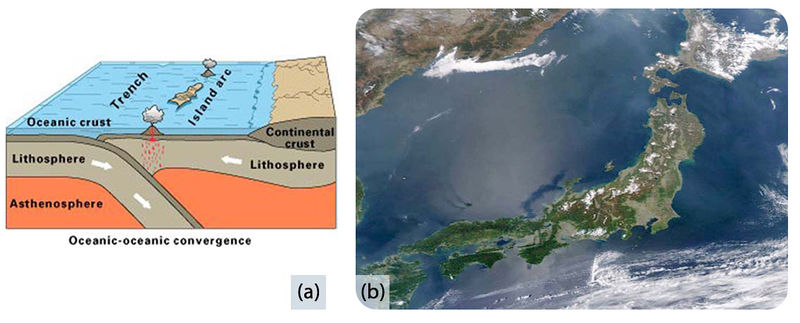

Ocean-Ocean

When two oceanic plates converge, the older, denser plate will subduct into the mantle. An ocean trench marks the location where the plate is pushed down into the mantle. The line of volcanoes that grows on the upper oceanic plate is an island arc. Do you think earthquakes are common in these regions (figure 10)?

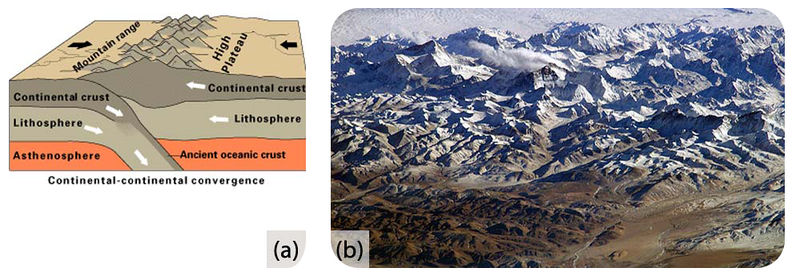

Continent-Continent

Continental plates are too buoyant to subduct. What happens to continental material when it collides? Since it has nowhere to go but up, this creates some of the world’s largest mountains ranges (figure 11). Magma cannot penetrate this thick crust so there are no volcanoes, although the magma stays in the crust. Metamorphic rocks are common because of the stress the continental crust experiences. With enormous slabs of crust smashing together, continent-continent collisions bring on numerous and large earthquakes.

The Appalachian Mountains are the remnants of a large mountain range that was created when North America rammed into Eurasia about 250 million years ago.

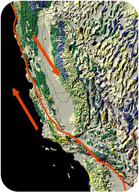

Transform Plate Boundaries

Transform plate boundaries are seen as transform faults, where two plates move past each other in opposite directions. Transform faults on continents bring massive earthquakes (figure 12).

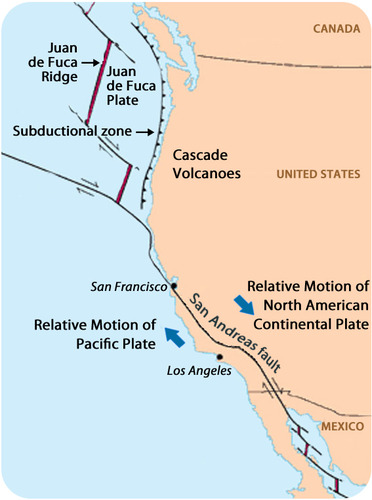

California is very geologically active. What are the three major plate boundaries in or near California (figure 13)?

Figure 13. This map shows the three major plate boundaries in or near California.

- A transform plate boundary between the Pacific and North American plates creates the San Andreas Fault, the world’s most notorious transform fault.

- Just offshore, a divergent plate boundary, Juan de Fuca ridge, creates the Juan de Fuca plate.

- A convergent plate boundary between the Juan de Fuca oceanic plate and the North American continental plate creates the Cascades volcanoes.

Earth’s Changing Surface

Geologists know that Wegener was right because the movements of continents explain so much about the geology we see. Most of the geologic activity that we see on the planet today is because of the interactions of the moving plates.

In the map of North America (figure 14), where are the mountain ranges located?

Figure 14. Mountain ranges of North America.

Using what you have learned about plate tectonics, try to answer the following questions:

- What is the geologic origin of the Cascades Range? The Cascades are a chain of volcanoes in the Pacific Northwest. They are not labelled on the diagram but they lie between the Sierra Nevada and the Coastal Range.

- What is the geologic origin of the Sierra Nevada? (Hint: These mountains are made of granitic intrusions.)

- What is the geologic origin of the Appalachian Mountains along the Eastern US?

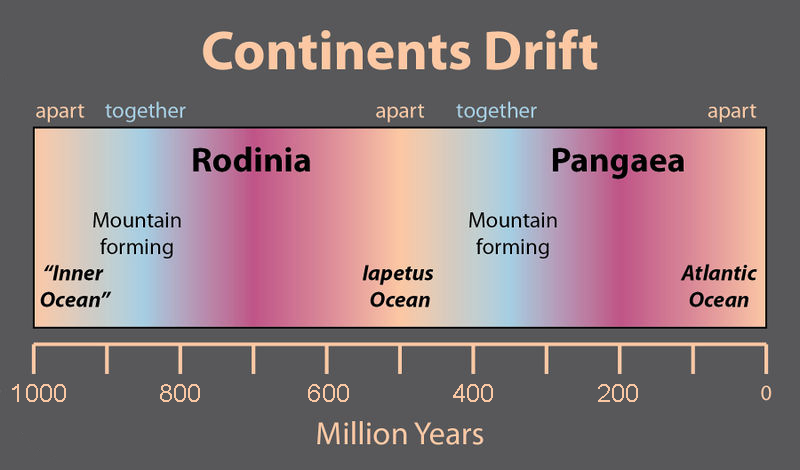

Before Pangaea came together, the continents were separated by an ocean where the Atlantic is now. The proto-Atlantic ocean shrank as the Pacific ocean grew. Currently, the Pacific is shrinking as the Atlantic is growing. This supercontinent cycle is responsible for most of the geologic features that we see and many more that are long gone (figure 16).

Plate Tectonics: Pangaea Breakup (produced by W. W. NORTON & COMPANY, Dr. Stephen Marshak):

Lesson Summary

- Plates of lithosphere move because of convection currents in the mantle. One type of motion is produced by seafloor spreading.

- Plate boundaries can be located by outlining earthquake epicenters.

- Plates interact at three types of plate boundaries: divergent, convergent and transform.

- Most of the Earth’s geologic activity takes place at plate boundaries.

- At a divergent boundary, volcanic activity produces a mid ocean ridge and small earthquakes.

- At a convergent boundary with at least one oceanic plate, an ocean trench, a chain of volcanoes develops and many earthquakes occur.

- At a convergent boundary where both plates are continental, mountain ranges grow and earthquakes are common.

- At a transform boundary, there is a transform fault and massive earthquakes occur but there are no volcanoes.

- Processes acting over long periods of time create Earth’s geographic features.

- Lippsett, “Laurence (2001). \”Maurice Ewing and the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.\” Living Legacies. Retrieved 2008-03-04; Lippsett, Laurence (2006). \”Maurice Ewing and the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory\”. In William Theodore De Bary, Jerry Kisslinger and Tom Mathewson. Living Legacies at Columbia. Columbia University Press. pp. 277-297.” ↵

- Korgen, “Ben J. (1995). \”A voice from the past: John Lyman and the plate tectonics story\” (PDF). Oceanography (The Oceanography Society) 8 (1): 19-20; Spiess, Fred; Kuperman, William (2003). \”The Marine Physical Laboratory at Scripps\” (PDF). Oceanography (The Oceanography Society) 16 (3): 45-54.” ↵

- Lippsett, “Laurence (2001). \”Maurice Ewing and the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.\” Living Legacies. Retrieved 2008-03-04; Lippsett, Laurence (2006). \”Maurice Ewing and the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory\”. In William Theodore De Bary, Jerry Kisslinger and Tom Mathewson. Living Legacies at Columbia. Columbia University Press. pp. 277-297.” ↵

- Heezen, “B. (1960). \”The rift in the ocean floor.\” Scientific American 203 (4): 98-110. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1060-98.” ↵

- Lippsett, “Laurence (2001). \”Maurice Ewing and the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.\” Living Legacies. Retrieved 2008-03-04; Lippsett, Laurence (2006). \”Maurice Ewing and the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory\”. In William Theodore De Bary, Jerry Kisslinger and Tom Mathewson. Living Legacies at Columbia. Columbia University Press. pp. 277–297.” ↵

- Korgen, “Ben J. (1995). \”A voice from the past: John Lyman and the plate tectonics story\” (PDF). Oceanography (The Oceanography Society) 8 (1): 19–20; Spiess, Fred; Kuperman, William (2003). \”The Marine Physical Laboratory at Scripps\” (PDF). Oceanography (The Oceanography Society) 16 (3): 45–54.” ↵

- Lippsett, “Laurence (2001). \”Maurice Ewing and the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.\” Living Legacies. Retrieved 2008-03-04; Lippsett, Laurence (2006). \”Maurice Ewing and the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory\”. In William Theodore De Bary, Jerry Kisslinger and Tom Mathewson. Living Legacies at Columbia. Columbia University Press. pp. 277–297.” ↵

- Heezen, “B. (1960). \”The rift in the ocean floor.\” Scientific American 203 (4): 98–110. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1060-98.” ↵