5 Roles of the Government in the Economy: Price Controls

Bettina Berch

Consider this

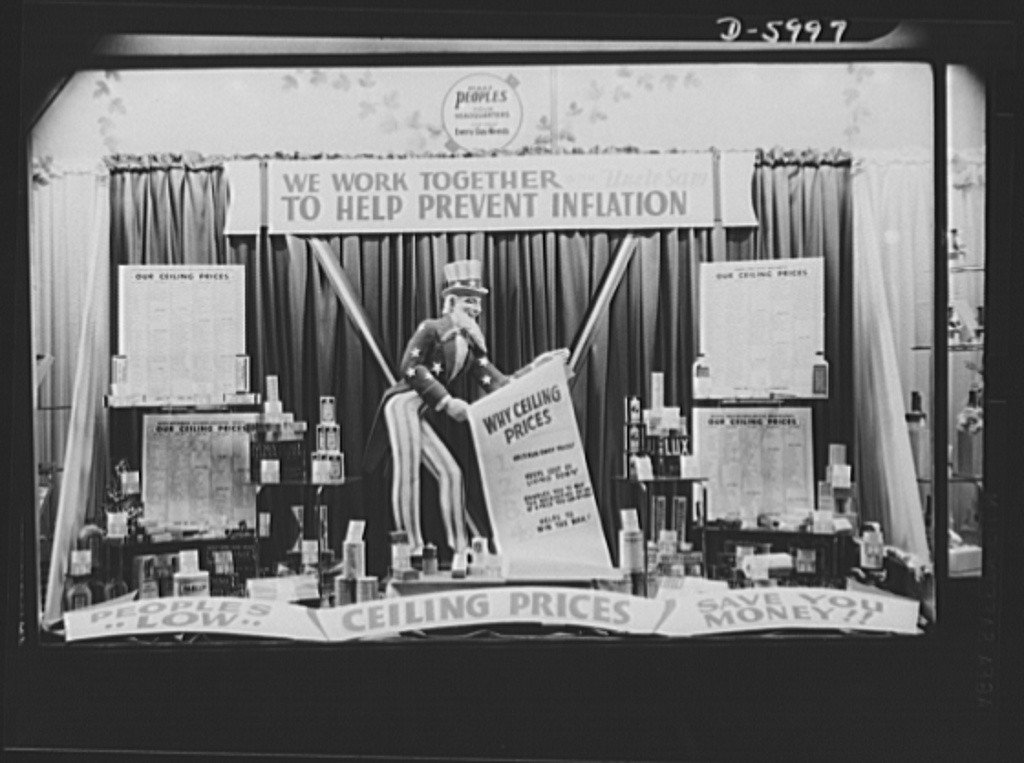

As we’ll be exploring in this chapter, one legitimate role for the government in a free enterprise, market economy, could be setting up price controls. Why do you think our government (represented by “Uncle Sam”) partnered with business to control prices when this photo was made in 1942?

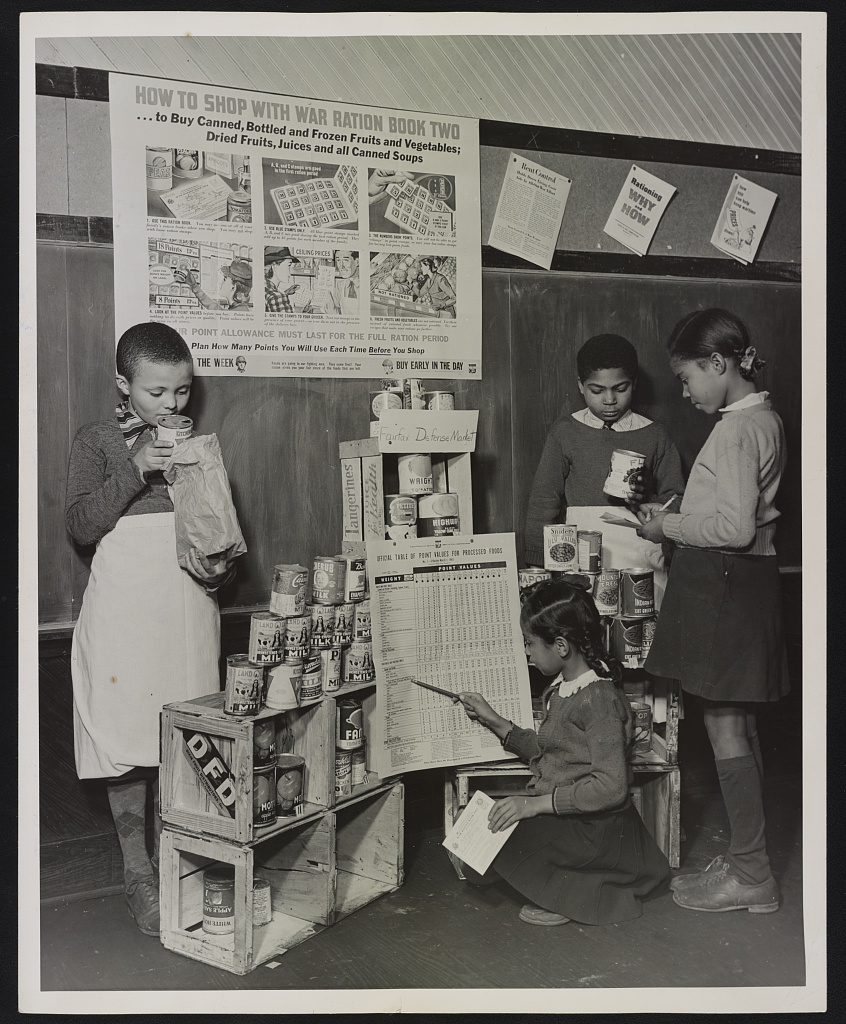

Successful implementation of price controls, in the days before the internet, took a lot of well-placed propaganda. Here, we see elementary school students (at a segregated D.C. public school, as this was pre-1954) learning to shop with rationing. Why would goods be rationed when you have price ceilings?

Markets, we have seen, are efficient at allocating goods to those who have the desire and the means to buy what’s for sale. Sometimes, however, societies want to allocate goods to people who do not have the money to buy them. Or they want to prevent people from buying those goods. Or they want to provide extra income to the people who are supplying these goods. Governments do these things by various means—laws, special prices, and taxation are key methods. We will look first at the economic tools involved, then see what happens in these markets when they are used.

Price Ceilings and Price Floors

A price ceiling is an upper limit on how high a price can go: it says the price for something—an apartment, a loaf of bread, an organ for transplant—cannot go above some stated price.

A price floor is a lower limit on how low a price can go: it says the price for something—an hour of work, a ton of wheat—cannot go below some stated price.

Since it can get confusing when you start working with these price controls, remember one basic rule—you can’t go above a ceiling, you can’t go below a floor.

Governments can decide to set ceilings and floors at any price levels they choose—above or below what they would have been without a law. So we introduce the concept of a binding price ceiling or floor to describe whether the law is having any impact on the marketplace. When a price control is binding, it’s like some piece of clothing you are wearing that’s binding—it’s tight, it’s something you feel, it’s having an impact. A binding price ceiling is a price set below market equilibrium; the market would want to take that price higher, but the price ceiling prevents that price from going there. A binding price floor is a price set above market equilibrium; the market would want to bring that price down, but the price floor won’t let it go there.

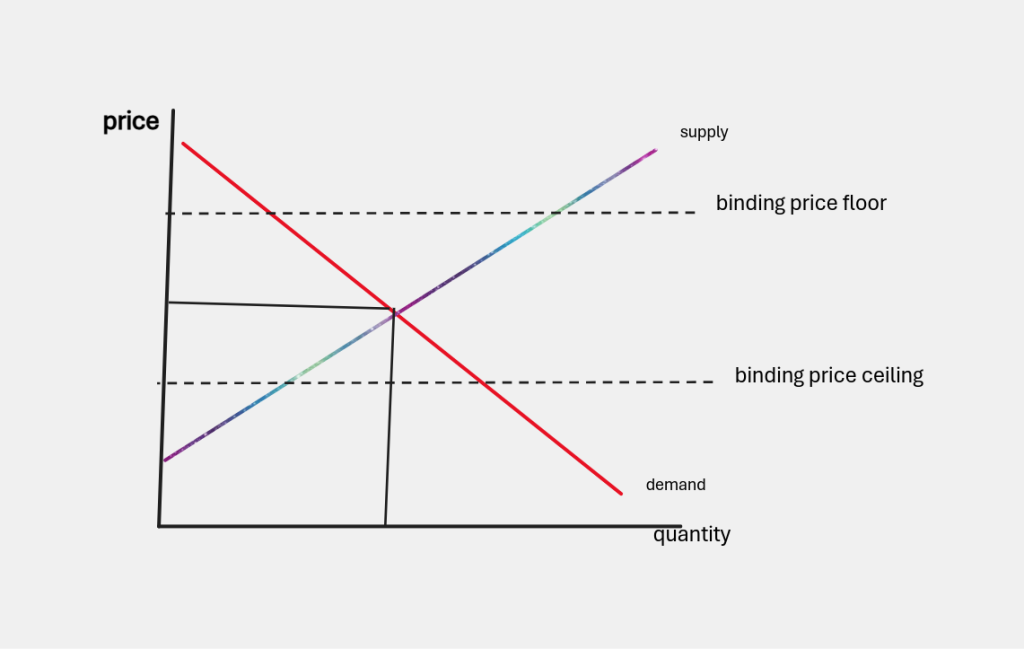

In the graph below, we see a binding price ceiling and a binding price floor:

Students are often confused to see that the binding floor sits ABOVE the binding ceiling on the graph, but if you think about what it means that each price control is BINDING, you understand why they sit where they do. When the price floor is above equilibrium, the price would want to fall down to equilibrium, but it is prevented by the price control—so this is a binding constraint. Likewise, when the price ceiling is set below equilibrium, the price would want to go higher, but it is prevented from rising by the price ceiling—so it is binding.

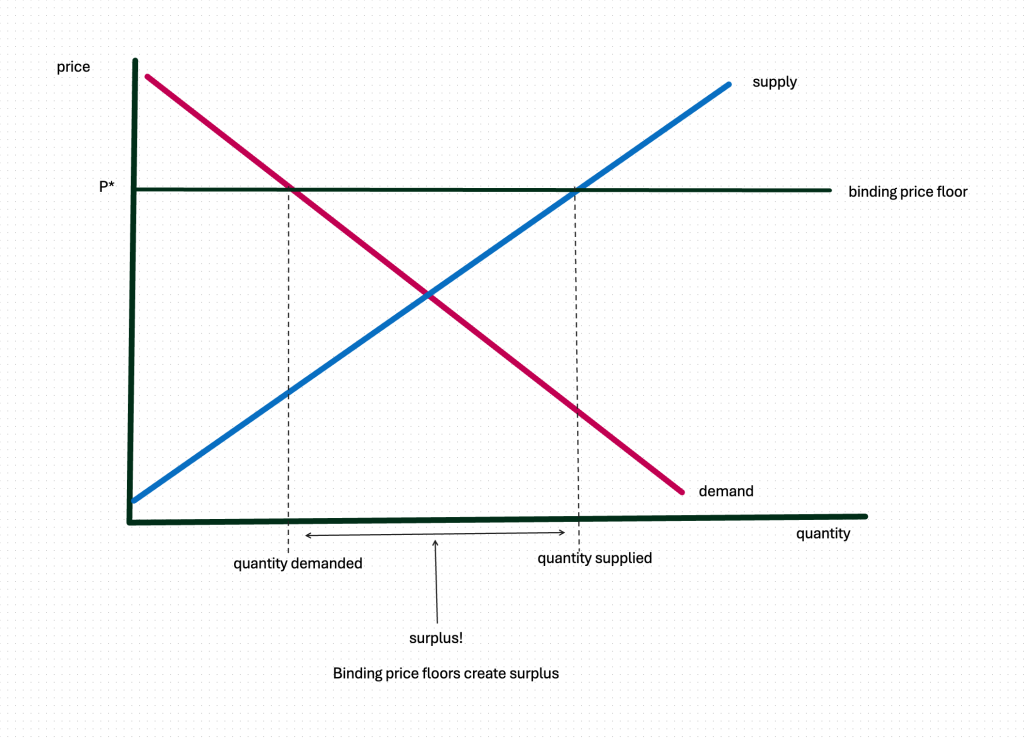

Looking at the graph, we see that demand and supply are not equal at the ceiling and floor prices. Let’s examine a binding price floor first:

This binding price floor creates a surplus.

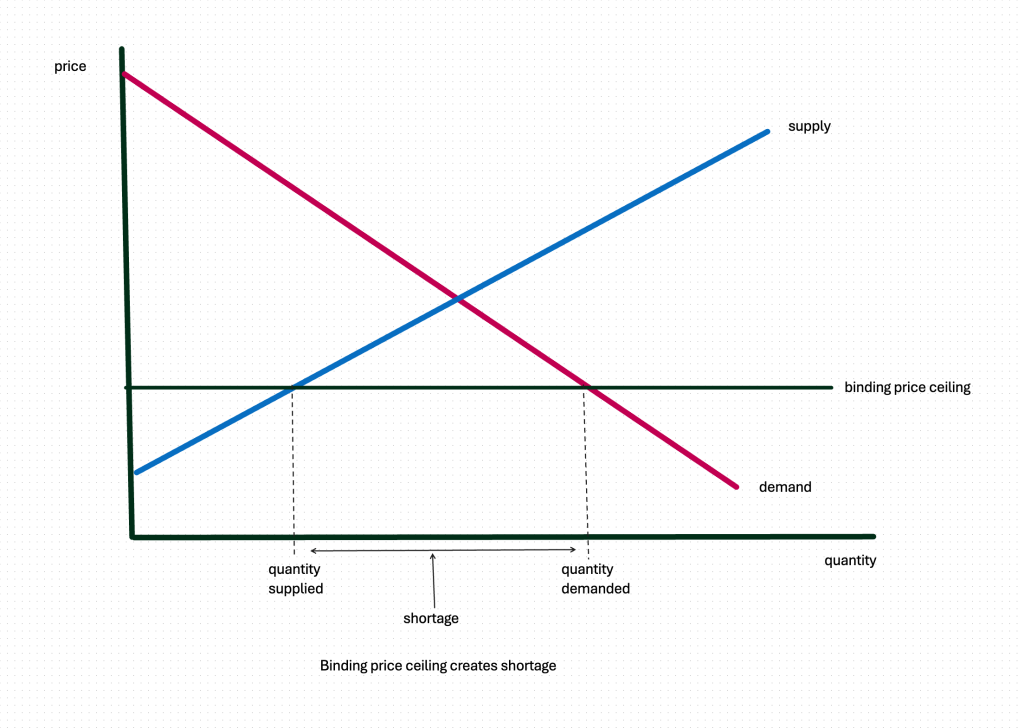

Likewise, we can draw a binding price ceiling:

This binding price ceiling has created a shortage. This is the normal impact of binding price ceilings and floors—they produce shortages and surpluses.

Real-Life Price Floors: The Minimum Wage

Now that we have the basic tools of analysis, let’s see how they help us analyze some situations in our economy today. Let’s start with one popular real-life price floor, the minimum wage. In 2009, the Federal government raised the minimum wage to $7.25 per hour for all covered workers. (This is up from $0.25 per hour in 1938). The Federal law specifies which categories of workers are covered under the law, and this is a ‘nominal’ wage rate, meaning it does not go up when inflation eats away at its purchasing power. This minimum wage was designed to put a floor under the wage rate for the lowest paid workers—no one should be paid less than this. Wages could always go higher—and if a state has a higher minimum wage in its laws, then an employer doing business in such a state has to obey the state’s minimum. (As of January 2014, 21 states and the District of Columbia have minimums higher than the Federal rate, and many states index their minimums to the cost of living.)

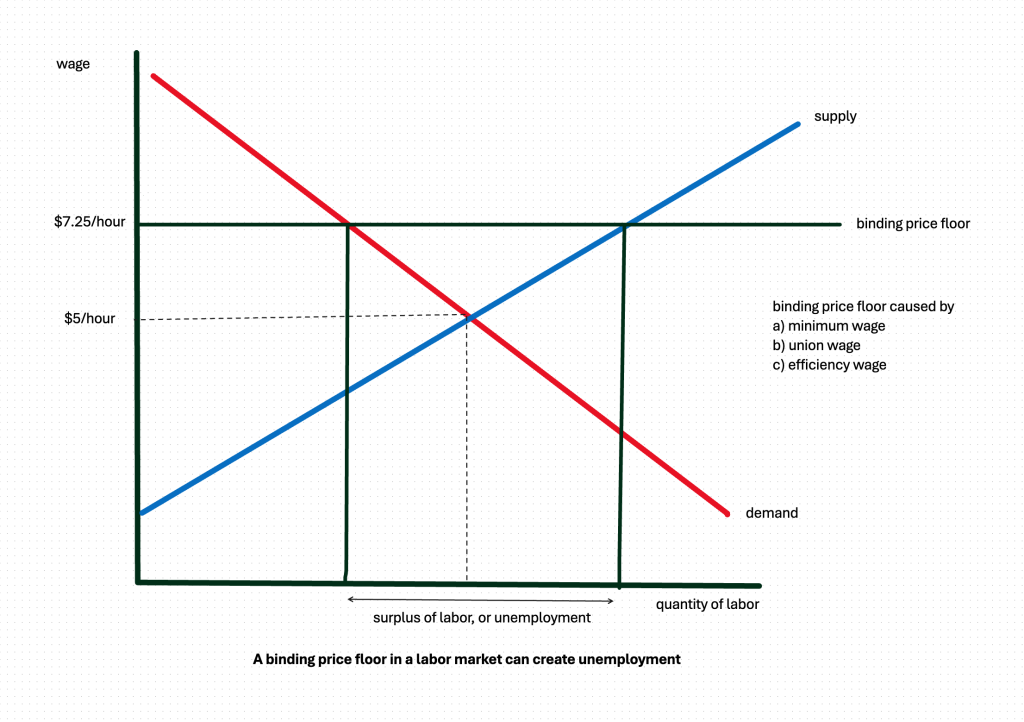

Let’s try graphing the minimum wage price floor with the tools we’ve just learned. First, we are going to have to decide if the minimum wage is binding—without the law, would the market wage be lower than the Federal $7.25? Or New York State’s $14.20 per hour? Since there’s so much employer opposition to raising the minimum wage, we might assume the law is binding, since otherwise, why spend good lobbying dollars opposing it? Let’s assume the market wage might be $5 per hour if there were no laws in effect, and graph it out:

Our minimum wage of $7.25 per hour is binding when we assume a market equilibrium rate of $5 per hour. At $7.25 per hour, the supply of labor is greater than the demand for labor—we have a surplus of labor, which we could call ‘unemployment.’ Indeed, this simple graph is the basis for many arguments against having a minimum wage, or raising the minimum wage. People opposed to the minimum wage argue that it causes unemployment.

Do you agree? Should you agree?

(And did you notice that we just shifted from a ‘positive’ analysis to a ‘normative’ analysis?)

Let’s start with the positive analysis—is this graph a factual portrayal of the labor market in the United States? We know the minimum wage line is accurate, but we certainly don’t have the space here to examine all the details of the supply and demand curves. But there is one issue that we could—and must– nail down: the question of whether the minimum wage is binding. For if the minimum wage is not binding, then there will be no labor surplus caused by the minimum wage. This brings us back to one of our original assumptions when we drew the graph, that the equilibrium wage would have been $5 an hour without a minimum wage law.

Is this true? Of course, it is hard to decide what a market wage would be if we did not have a wage law—it’s a counterfactual proposition. Who knows what it would be? But we can make some educated guesses. Consider the fact that most big cities have areas where people hire day laborers, often people with no skills and no documents, people who will work for the day for cash wages. No one invokes the minimum wage law in these marketplaces. Data from California, a large market for day labor, shows an average wage of $18 per hour for day labor. This is substantially higher than the Federal minimum of $7.25 per hour or the California minimum, at the time, of $9 per hour (in 2023, California’s minimum wage is $15.50/hour). Similar findings exist for other areas. So it may be very hard to argue that the Federal minimum wage is binding, in which case, it is probably not ‘causing’ unemployment.

Of course, a person could argue that the rate for day laborers is not entirely comparable, since these workers are not hired for 40-hour work weeks. So let’s move on to the normative question—if we agreed that the minimum wage ‘caused’ some amount of unemployment, should we eliminate it? Or at least not raise it?

This again is too large an issue to answer here. But we might take a different approach. What if we kept the minimum wage and did something to reduce or eliminate the labor surplus (unemployment) that it caused?

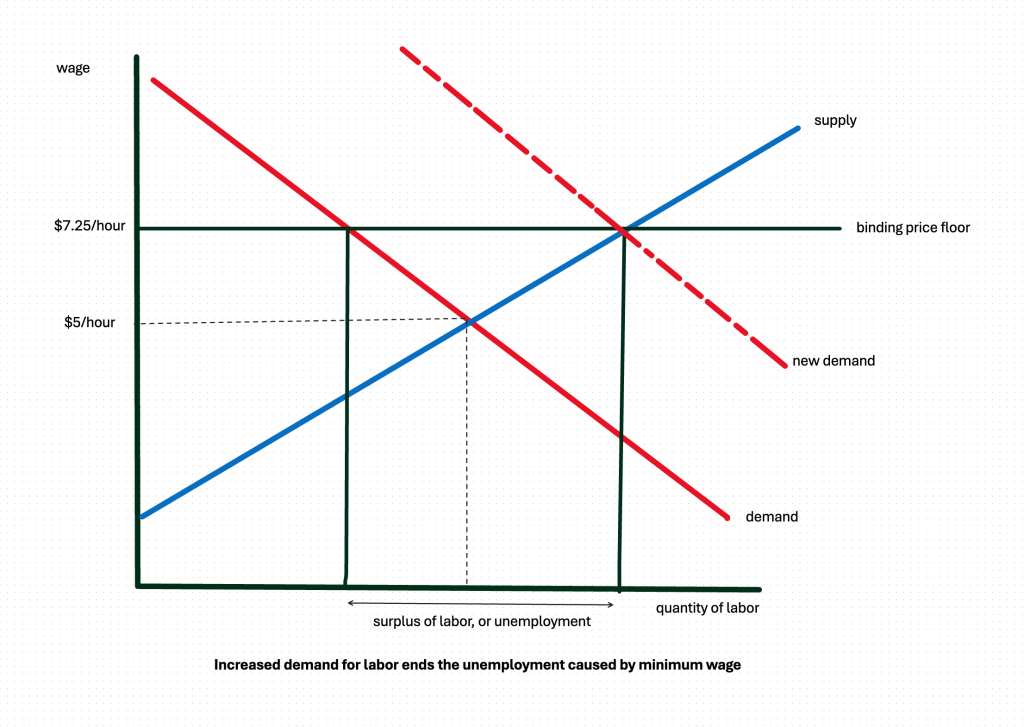

How? Well, remember that we are policy-makers, so we could design some programs to shift the labor supply or labor demand curves to eliminate the labor surplus. Suppose we created some ‘economic opportunity zones’ that gave businesses tax credits to open new companies in areas with high unemployment. This would shift our labor demand to the right and close the labor surplus:

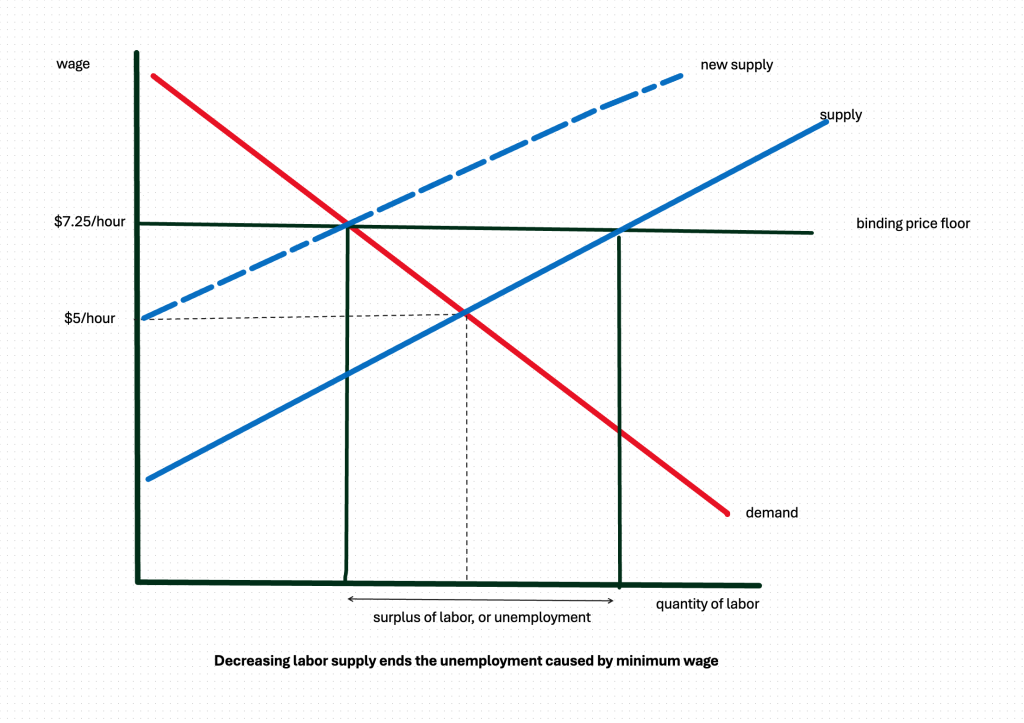

Alternately, we could shift labor supply to the left, by various policies. Tightening up labor documentation, so that workers could not be employed by anyone without paperwork, would certainly shift labor supply to the left. Or, we could take a more progressive approach, and require all young people to stay in school until age 21, or allow retirement from the labor force with full benefits at age 60. Both would reduce labor supply:

The point is that with our economic tools, we can analyze an economic situation from both a positive point of view (what are the relevant facts?) and a normative point of view (how do we get the outcomes we would prefer?).

Real-Life Price Ceilings: The Usual and the Unusual

All around us there are price ceilings—maximum prices set by law. In New York City, there is a maximum price of $75 for taxi rides to JFK airport. There are also maximum rents/rent increases for rent-controlled and rent-stabilized apartments. With each of these price ceilings, the idea has been to make some common item affordable to most people. When this price ceiling is binding, it creates shortages. These shortages may mean there are long lines of people waiting to get the artificially cheap item, or bribery to cut the line, or even forms of discrimination. If you were a landlord with a rent-controlled apartment to rent out, you would know there’s a long line of people outside your door eager to rent it. You could take an illegal bribe. You might decide not to fix the place up before re-renting it, since there are plenty of people eager to take it just the way it is. Or you might decide that as long as you can’t get much rent for it, you will at least refuse to rent to people who give you headaches, like noisy college students or people with children. Or you might decide to rent to your own ethnic group, or your own racial group–in other words, discrimination. Most of these choices would be illegal, but that might not stop you.

Some price controls hide behind other social arrangements. For example, most countries have armies, but not a lot of money to spend on them. The below market, low wage offered to military recruits is effectively a binding price ceiling–which creates a labor shortage. How can a country close that gap? They can require military service, institute a draft. Of course, a draft can be socially unpopular, so a country might switch to what is sometimes called a “volunteer army,” which does NOT mean they are not paid—it just means a market wage is offered for military service, and people apply for this work as they might apply for any other labor market job.

A special price ceiling occurs when the law bans sales but allows donations: the situation with human organ transfers in the United States after 1984. The sales ban effectively puts a price ceiling of zero on kidneys, eggs, and other body parts. While this decreases the supply of organs for people in desperate need of a transplant, it satisfies many peoples’ moral qualms. Remove payment and you can be sure that economic desperation is not the motivation for donation. We also ban blood sales as a way of screening out potentially unhealthy donors, while allowing plasma sales. Women may not be paid for donating their eggs to a fertility clinic, but they may be paid large amounts for medical care, housing, or other kinds of ‘compensation.’ People who ‘donate’ blood when supplies are very low, may be offered a ‘free’ Starbucks card.

Should we have price controls?

The market price may seem unfair (a normative judgment), because it allocates things to the people who can pay, the people who have the money…but that might be less unfair than what happens when the market mechanism is removed and price controls rule allocation. In France, there used to be a maximum price for the standard baguette, the loaf of bread most people ate with every meal. I can remember going to France in the old days (before 1987!) and trying to buy one of those lovely, price-controlled baguettes. I’d walk into a bakery, the owner would know I was not one of her ‘regulars,’ and she’d tell me they were all sold. I would point to the toasty loaves in the bin, and she’d tell me they were already ‘reserved’—for her usual customers. I was welcome to buy another sort of loaf (more expensive, of course).

When you study economics, you gain a little insight into some of these transactions!

Some Useful Materials

Watch a video on price ceilings.

Try a video on price floors, focusing on the minimum wage.

Media Attributions

- Uncle Sam Says, ‘price controls work!’ © Liberman is licensed under a Public Domain license

- schoolkids and rationing © Roger Smith is licensed under a Public Domain license

- price controls © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- price floor © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- binding ceiling creates shortage © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Binding price floor creating unemployment © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Increase demand for labor to remove unemployment © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- reduce unemployment by decreasing supply of labor © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license