17 The Federal Reserve

Bettina Berch

Consider this

From the start of the very first bank in the world, there were probably people who blamed that bank for their problems. Why were the protestors in this photo angry with the Federal Reserve? Could you imagine yourself marching in a protest against the central bank?

Today’s fiat money has Federal Reserve Note in big letters across the top. Today’s banks don’t just do as they please, they follow the Fed’s (slang for the Federal Reserve Bank) rules. It’s time we focussed on the Fed’s history and functions.

Banking in the United States before the Fed

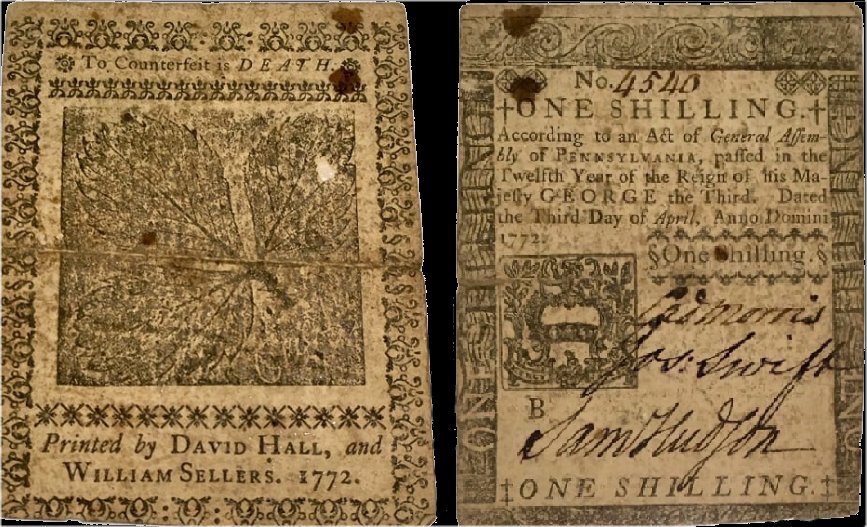

Banking in colonial America was unregulated. The British didn’t want their colony to mint their own coins, so most of the coins in circulation came from the Spanish empire, which meant there was little uniformity. Colonial legislatures issued some paper notes, which were also fairly irregular. The issuers of this 1772 shilling note (worth about 20 cents and described as the size of a playing card) felt the need to caution against counterfeiting, right across the top!

Some forward thinkers, like inventor Benjamin Franklin, were researching how to embed security features into paper money. It wasn’t until after independence that the creation of a national currency was possible. Throughout the nineteenth century, there were attempts to create various types of commercial and state banks, even attempts to establish a central bank, but factional politics were fierce. Lobbyists for farming interests fought “tight” money policies, since they regularly needed to borrow to finance planting seasons. Backing paper money with gold or silver was an issue for others. Deposit insurance was tried and rejected. Late nineteenth century immigration added immigrant banks to the panic-ridden private banking landscape. While the major financiers of the 1890s onwards, some of the so-called Robber Barons, worked to eliminate smaller, prone-to-failure banks, they got nowhere until December 1913, when President Wilson signed the Federal Reserve Act into law.

A very private group of bankers and financiers had studied the central banks of Europe and the weak points of the American financial system over the previous century to design a central bank for the United States, one that would respect state authorities but bring the various states under a single, central governing board. This central bank would be as independent of the Congress and the president as possible, by financing itself, and having its officers serve long terms with re-elections in non-presidential election years. Specifically, there would be 12 regional Federal Reserve banks governed by a national board with 7 members. The chairman and vice chair of the board of governors would be nominated for 4-year terms by the president and confirmed by the Senate. The national board members would serve 14-year terms. Once approved, these people couldn’t be fired by disgruntled presidents or members of Congress, so they would be freer to act in the country’s interests, rather than always trying to save their own jobs. And unlike most government agencies, the Federal Reserve would finance itself, so it wouldn’t face threats of being “de-funded” by an angry Congress. (Actually, the Fed sends any budget surplus to the U.S. Treasury–in 2022 they sent some $76 billion.)

The Fed’s functions: regulation of the banking system

Given the banking chaos of the preceding century, it’s not surprising that the first function of the Fed was to regulate the health and smooth operation of the American banking system. The regional federal reserve banks regularly audit the books of their member banks as well as other financial institutions in their region. As you can imagine, in the digital era this means monitoring key data that could indicate problems. When a red flag goes up, the regional Fed is supposed to dig deeper and work with the troubled institutions. Mostly, this works well; when it doesn’t, as with the recent failure of the Silicon Valley Bank, the Fed takes a lot of blame.

Other Fed functions focus on inter-bank transfers. Do you ever wonder how you can deposit your paycheck drawn on Citibank into a Chase account and there’s no problem? This would have been a big headache for pre-Fed Americans, but the Fed ensured that check-clearing between banks works smoothly. Likewise, the Federal Reserve stands as a ‘lender of last resort’ to member banks, maintaining a discount window, pre-2020, for member banks that fell below their reserve requirements.

The Fed’s functions: setting monetary policy for the country

The second big function of the Fed is to create the monetary policy for the country. Let’s break that down. First, the Federal Reserve has to do research on economic activity in all regions of the country. What’s been going on with housing costs? Unemployment? Prices? Are there clues to future trends from things going on now? Each regional branch adds anecdotal information to the official information in the so-called Beige Book. All that information has to be discussed and analyzed to get a reading on how the overall economy is doing and which are the weak/strong areas. It’s the Fed that puts this picture together. After that, they have to decide what policy is needed to stay on track with their two main goals: keeping price inflation at 2%, and keeping the unemployment rate below 4% for the current economy.

Two (old-school) tools the Fed used, pre-2020: the reserve requirement and the discount rate

Traditionally (before 2020), the Fed had three main tools it used to conduct its monetary policy. The first was setting the reserve requirements for banks. We mentioned this in the last chapter, when we discussed fractional reserve banking. We said that in the past, our Fed set the reserve ratio at approximately 10%. That figure was always different for different size banks, but in the Covid era that was set at zero, so it went away completely. But when they instituted that 10% requirement, they created another tool–the setting of the discount rate, the rate the Fed charges member banks to borrow overnight funds.

Why would a bank need to borrow funds overnight, you might wonder? Think of it like this, although it’s simplified. Let’s say you manage a bank. Your staff spends the day taking deposits and writing loans. At the end of the banking day, you go over all the books, totaling up the deposits and loans. Suppose you ended up loaning out too much money relative to how much was deposited, so you fell below the 10% requirement?

The first thing you might do, is call up other bankers and try to borrow their extra reserves overnight, until the next banking day. If someone had extra to loan, they’d charge you the federal funds rate. If no one had extra reserves to loan, you’d have to reach out to the Federal Reserve’s discount window and ask to borrow from this ‘lender of last resort.’ So yes, the Fed will loan you reserves overnight. But it isn’t free. The Fed charges the discount rate, which they set. If they set a high rate, they’re leaning on you to be stingy with loans the next day in your bank. You’ll cut back on loan-writing out of fear of having to revisit the discount window and get charged even higher rates. On the other hand, if the Fed had set a low discount rate, you’d return to your bank the next day and be generous with loans, figuring if worst came to worst, you’d go by the Fed’s discount window and get those low low rates again! When the Fed sets a high or a low discount rate, they’re sending a signal to banks: low discount rates and they want you to be expansive, high discount rates so you’ll be cautious, contractionary.

These two tools go together. Meeting the reserve requirement is what would drive you to the discount window, where the signal of high or low rates would shape your loaning behavior going forward. BUT. In March 2020, the Fed dropped our reserve requirement to 0, allowing banks to lend out as much as possible as we faced a period of uncertainty on the brink of Covid. (Again, here’s a useful chart of other countries’ current rates.) There’s no sign that the Fed intends to raise this reserve requirement above 0 anytime in the future. If you’re wringing your hands, saying”I don’t get it,”–well, there are a lot of folks who’d join you. By dropping the reserve requirement, the Fed effectively dropped a lot of need for that discount window. What could the Fed be thinking? Partly, the Fed was acknowledging that banks keep enough reserves on hand, anyway, without the reserve requirement, to meet the transactions needs of customers.

Another old-school tool the Fed used to reach policy goals: open market operations

The third classic tool the Fed used to carry out monetary policy has been open market operations (OMOs). Supposed the Fed decided that the U.S. economy needed some stimulus. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) could invite major bankers to an auction, where the Fed might be buying bonds from the bankers’ portfolios for example. Bankers would show up with their portfolios and the Fed OMC would try to buy the bankers’ bonds. Since this is an auction, the FOMC might open with a typical level bid to buy those bonds. The bankers could hold back, seeing if the FOMC would offer a higher bid. The end result? Two things. First, the bankers finally sell their bonds, so they’re walking out with extra liquidity for their banks. The next day, there will be a lot of loans written!

How to understand the rate of return on bonds

The second result comes from that higher purchase price on these bonds, when the Fed had to offer more than usual to buy them. Why does this matter? Understand it like this–there’s a relationship between the purchase price of a bond and its rate of return. Imagine there’s a bond worth $1000 on maturity. Imagine you’re a banker at one of the Fed’s OMC auctions, and the Fed’s trying to buy your bond from you. What’s the implication of the different prices the Fed might pay?

| The purchase price of the bond | bond’s value at maturity | the return on that Bond (aka “the interest rate”) |

| $100 | $1000 | HIGH!!! |

| $500 | $1000 | medium |

| $900 | $1000 | Low |

The more that’s paid to buy the bond–its purchase price–the lower the return. The lower the purchase price, the higher the rate of return. (If this is hard to understand, just think about the time you got a really expensive pair of sneakers for an incredibly low price–you gained a lot there, compared to paying full price, which wouldn’t be such a great deal. When the purchase price is very low, you’re ‘making more’ on the deal, or a higher rate of return.)

The impact of an open market operation on the economy

In this open market operation, the Fed was trying very hard to buy bonds, which pushed up the purchase price. This lowered the rate of return, effectively lowering the interest rate in the economy, we would say. This stimulates economic activity, as business sees a lower cost to borrowing money (the lower interest rate) and decides to build more factories. That’s in addition to the first effect we mentioned, that the bankers, having sold bonds to the Fed, walked out with more liquidity to add to their banks’ capacities to loan out funds. Bottom line: When the Fed’s open market committee buys bonds, they expand the economy two ways: through an increase in the money supply, and by lowering interest rates.

What if the Fed decided the economy was over-heated? The open market committee could invite bankers to an auction, this time warning them to bring lots of cash, because the Fed would be selling them bonds! The Fed could open the auction by offering to sell bonds for $500. The bankers wouldn’t say a word! The Fed would have to keep offering their bonds for lower and lower prices, until finally bankers decided to buy them. The lower purchase price means the rate of return on those bonds is very high, meaning a higher interest rate for the economy. With higher interest rates, home builders postpone new home construction, since it’s more expensive to borrow money. Factory owners think twice before expanding. Higher interest rates mean lower investment, dampening economic activity. Second, when bankers bought bonds, they went back to their banks with less liquidity. This open market operation, with the Fed selling bonds, dampened economic activity two ways: it produced a higher interest rate which would depress investment, and it reduced banks’ liquidity, so they’d be writing out fewer loans. It has to be pointed out, that this whole auction situation is completely voluntary. No one forces banks to attend or bid or sell. The profit motive guides behavior, not the iron fist.

The Fed’s new tools: IORB rate, or ‘interest on reserve balances’ rate, the repurposed discount rate and ON RRPs (overnight reverse repurchase agreements)

After the world financial crash in 2008, our Fed started implementing some new tools. Some replaced mechanisms that weren’t as effective in a world with interest rates close to zero, with banks that were flush with ample reserves. As we read in the last chapter, in March 2020, the Fed eliminated the reserve requirement, which also left the discount rate somewhat ineffectual. So what did the Fed introduce instead?

The Fed had been creating a new tool: paying interest on member bank deposits at the Federal Reserve. If you are a bank and you have extra reserves you’re not loaning out, you could keep those reserves in your own vault–or park those funds at your regional Federal Reserve bank. If the Fed decided to pay you a 5% IORB (interest on reserve balances)–you’d park those funds at the Fed for sure. In addition, that would become the lowest rate of return you would accept for loaning out that money to anyone, because it would be the safest. (If a restaurant wanted to borrow money from you at 4%, you’d say no, I can get 5% from the Fed with no risk at all!) The Fed’s IORB becomes the ‘ground floor’ borrowing rate for the economy, forcing everyone else’s rates to be higher than what the totally-safe Fed is offering. A new tool is born!

What about controlling the peak of interest rates, the high end? Here the discount rate finds a new role. Recall, the discount rate is what the Fed charges banks that want to borrow funds. If the Fed set that rate at 4%, it means other parties couldn’t try to charge a bank 5% to borrow–because they could just go to the Fed and borrow at 4%. So with the IORB and the discount rate, the Fed can set lower and upper limits for the interest rate, which is a powerful way for addressing an economy that needs to grow or get slowed down.

There’s one problem here. The Fed’s upper and lower bounds on the interest rate are effective when they’re an option for borrowing or lending for all the major players. But only member banks can deposit reserves at the Fed and earn the IORB, or borrow at the discount rate. What about all the other big financial institutions, like Vanguard or Fidelity mutual funds, or other non-bank players in the financial world? Their financial resources are huge, making it important for the Fed to find a way to make them responsive to Fed interest rate cues. The solution– ‘overnight repurchase agreements’ (known as ‘repos’) and ‘overnight reverse repurchase agreements’ (known as ‘reverse repos’). With a ‘repo,’ the Fed buys securities from a financial institution like a mutual fund, for example, with the understanding that it’s going to sell them back soon (overnight!) . The fund might do that to gain some liquidity. It’s a lot like a loan, with the Fed holding the securities as collateral. With a ‘reverse repo,’ it goes in the other direction. The Fed sells securities to the mutual fund, which can now earn some interest on its excess reserves (more or less like a member bank could earn that IORB by leaving reserves with the Fed).

Repos and reverse repos allow non-banks to gain interest by parking excess funds overnight with the Fed, or liquidity by borrowing overnight from the Fed. Since it’s the Fed that’s setting the rate of return on these activities, these repos extend the Fed’s influence to the non-bank world.

We have seen the enormous role of the Federal Reserve in regulating the banking system and in determining/executing monetary policy. We have seen that the Fed uses its tools–among other things– to raise or lower the size of the money supply. You may be thinking, ‘All my life, I never knew how big the money supply is–why should I start caring now? What difference does it make?’

Good question for the next chapter!

Some Useful Materials

Watch a video on how the FDIC protects consumers when banks fail.

Watch a video on why the Fed uses interest rates to control inflation.

Listen to a podcast on the medieval origins of modern banking–the Knights Templar!

Read about the Fed’s new tools. This is an important, step by step walkthrough of how IORB and ON RRP rates work.

Watch a video on the new Fed Tools.

This page has links to a set of 4 short videos on how the Fed uses its new tools. Easy to follow!

Media Attributions

- Protesting the Federal Reserve © Justin Ruckman

- One_Shilling,_printed_1772 is licensed under a Public Domain license