12 The Future of Work

Bettina Berch

Consider this

This is a modern automotive assembly plant. How many humans can you find in the photo? At first, American automotive jobs were lost to cheaper labor in other countries. Now, in many of those factories, that cheaper labor has been replaced by automation. Do you think it’s a big loss for humankind? Did assembly line work offer workers more than a paycheck?

In the last chapter, we defined employment terms (unemployment, labor force participation rate, etc) and took a look at the data on employment demographics. We saw that the youngest workers (16-19 years old) of any color experienced the most unemployment, with African-American and Hispanic youth experiencing scary high rates of joblessness. Almost 1 in 5 of these teens of color are actively seeking a job but not getting one. Youth unemployment is also a big problem in many other developed countries (Great Britain, Japan, China, to name a few); largely because it doesn’t end well. An acronym was invented to describe this: NEET (not in employment, education, or training). What are these folks living on? What do their futures look like?

The future of work is not just a problem of unemployed teens. How will increased automation, artificial intelligence, and new pandemics change the way people work in the near future? Will there be fewer jobs to go around? How will we support ourselves if machines are doing so much of the work, that having a job is sort of unusual? Can you even imagine what that would be like?

We can look at the past for some insights into the future

While history is rich with insights, let’s look at two periods: the Black Death (1347-1351) and the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain (1760-1840). Each of these disruptions offers useful lessons.

The so-called ‘Black Death’ was a bubonic plague pandemic that swept Western Eurasia and North Africa, killing 75-200 million people, roughly a third to a half of Europe’s population, the area hardest hit. The plague was inexplicable for people unaware of virus transmission. Beyond the mass deaths, the countryside might have looked jarring: fields full of grain, trees bearing fruit–but with so many peasants dead, fewer people were left to harvest anything. The upper classes tried to force their serfs to work, but faced a medieval version of the ‘Great Resignation’ . Peasants revolted, refusing to work or demanding higher wages to afford the higher cost of food. Governments passed stricter and stricter laws forcing peasants to work and punishing those who refused. The uprisings of the late 14th century were increasingly bloody and violent, resulting in a re-balancing of social power.

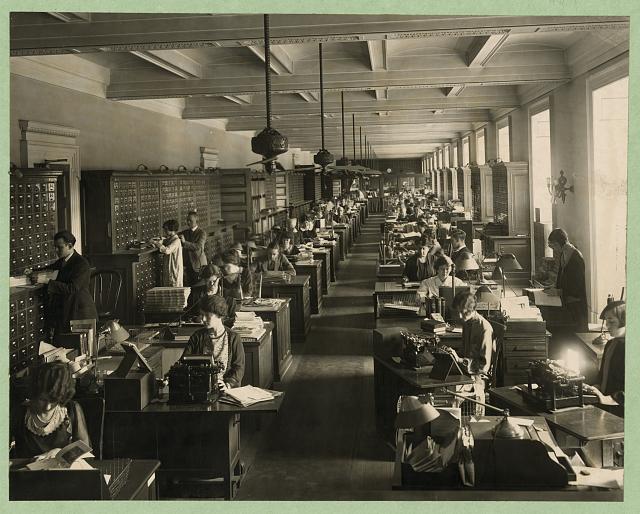

Britain’s Industrial Revolution in the eighteenth century started with innovations in the textile industries, with the mechanization of spinning and weaving. Before these innovations, people spun wool on spinning wheels and wove it into fabric on handlooms. They worked at home, in the daylight or by candlelight, most days a week, perhaps stopping work for Sunday prayers. They sold their product to a merchant; they were paid ‘piecework,’ we would say. With the invention of new machines to spin and weave, machines that required more than the foot power of home production, the factory system was born. The factory brought the machines, the workers, and the power source (water wheels, steam) all under one roof, for a set working day and an hourly wage. After production was moved to the factory, the business supervisors got their own roof too–the office. Actually, the modern office of 2020 is surprisingly similar to the office of 1920–rows of workers at their desks, all focused on their machines:

What are our takeaways from the Black Death and the Industrial Revolution? What are the implications here?

- The shortage of workers after the plague (and maybe the serious brush with death that survivors must have felt) led to peasant rebellions–against being forced to work, against inadequate wages. Flash forward to 2023 and the waning of Covid–many people quit jobs for higher-paying ones, refused to go back to offices, and pointed out the gap between what they were making and what what their bosses were making.

- Before the Industrial Revolution, most of us worked at home. Since our time could be used on a lot of things and no one was supervising us, we were not paid by the hour but by the piece, by our output. Think about the arguments employers make nowadays for moving us back to the office–that people multitask at home, that people are not as productive working at home. The pre-industrial world solved this problem by paying piecework, for output. Is that even possible for remote workers today?

- Office space is expensive: in HongKong, it runs $265 per square foot. In London, it’s $181 a square foot. Businesses that downsize or even eliminate their offices when their leases expire, may have a competitive advantage in their markets. Maybe we will all be working from home in ten years!

How will increasing automation shape the future of work?

Since the days of the Industrial Revolution, people have been warning that machines will replace people at their jobs. In many cases, it’s true. Phone calls used to be routed manually by telephone operators. Customer service desks used to be staffed by people, not computer software generating (frustrating) responses. While it is easy to tell each other horror stories about how we’re all going to be displaced by automation, let’s stop and look at what’s actually happened in the real world.

Let’s take the example of bank tellers. When was the last time you asked a bank teller to take money out of your account? Never? In real life, you drop by a kiosk, or even a bank lobby, sometime late at night and get the cash from an ATM. There’s no teller needed. You would think the ATM has displaced millions of bank tellers. But you’d be wrong. From 1970 to 2017, the number of human tellers has increased from about a quarter of a million to half a million. And the numbers keep growing. What’s the story? Bank tellers don’t spend much time dispensing cash anymore. They’ve become sales people for products banks are promoting (new CDs! ARM-mortgages!) or problem-solvers for customers who can’t access their accounts. Economist David Autor also argues that when some part of your job gets automated, the other parts, the human responsibilities, become more important. Then too, automation may replace some human jobs, but because our consumer wants and needs are always expanding, we’re always wanting more stuff, so there’s new demand for more workers all the time. This positive outlook comes with some caveats. There’s no guarantee that job quality won’t change; after automation, available jobs in many fields may not be as fulfilling as they used to be. There may be a hollowing out of middle-skill jobs, as AI learns to do them more consistently than we do, leaving just no-skill jobs and very-highly skilled jobs, with nothing in-between. Bottom line–workplace changes will impact some people and some fields more immediately than others.

What if we lose jobs to automation and AI? How will people live without a paycheck? Could the UBI be the answer?

For most of us, our income (what we live on) comes from our jobs. If we are looking at a future that needs fewer people with jobs, where would our income come from? This has led more people to think about cutting that link between income and jobs. What if every person received some fixed amount of money every month from the government that was unrelated to a job (like a paycheck) and unrelated to poverty (welfare)? This kind of payment has been given many names–the most popular might be UBI, universal basic income. In some parts of the world, the UBI is loaded onto a monthly debit card, with conditions on where it can be spent. In other places, it’s an annual payment. In some areas it’s an experiment with a fixed end date. In others, it’s only available to people out of work, or for single people raising children.

It’s great that there are so many experiments in diverse areas–then policymakers can evaluate what works best and what’s definitely a bad idea. Ideally, we don’t want the UBI to turn everyone into ‘couch potatoes,’ only getting up to go cash the monthly check and restock the beer. We want a UBI that supports healthy lifestyles (however that’s defined), that doesn’t disrupt the existing incentive systems in society. For example, if people go to college because they think it’ll get them a better job, we wouldn’t want the expectation of a lifetime UBI to discourage them from bothering with college. You might already suspect that the size of the UBI is going to be critical. If it’s too small, it’s not useful, especially if it’s a substitute for a paycheck. Too large, and we wonder if our government can afford to issue it to everyone. Let’s look at some real life examples.

Current, large-scale UBI

For over 40 years, full-time residents of Alaska have received an annual PFD (permanent fund dividend), an amount based on state revenues from oil and mining. While the annual amount varies, it averages about $1600 per person, per year. Research indicates that the PFD has not depressed employment in the state, although there’s been a small increase in part-time employment, which is hard to interpret. While the PFD is popular with Alaska residents, it’s not a huge sum and because it’s paid annually in a variable amount, it might feel more like a bonus than a regular income.

Gyeonggi Pay, in South Korea, is large scale UBI program with some interesting twists. The Gyeonggi province started making UBI payments to 24-year olds in 2016, with a series of variations on the amounts and eligibility. It expanded in 2018 to all residents, with payments reaching the equivalent of $430 per month. The most interesting feature they included was a mandate for local spending; Gyeonggi Pay, disbursed as a debit card, could only be spent with local merchants. So during Covid, New Yorkers, for example, avoided local shops in favor of big-box-store deliveries, leading to the collapse of small businesses. But small Gyeonggi merchants saw a 54% increase in sales, thanks to people spending with their Gyeonggi Pay cards. Governor Lee Jae-myung, who has actively promoted this UBI, says it’s not a welfare plan but an economic policy to address what he calls the Fourth Industrial Revolution, the end of the ‘labor era.’ If you’re wondering how the province (or the country, if it were expanded) would pay for this, Jae-myung is bold–he calls for a ‘robot tax.’ If the home province of manufacturing giants Daewoong and Hyundai and Samsung proposes a tax on robots, maybe we should be listening!

The promise of UBIs

Small UBI experiments, set-up to see if participants can improve their quality of life with a monthly stipend, are operating in cities across America, in countries around the world. When an American presidential candidate like Andrew Yang in 2020 makes a national UBI a plank in his platform, it starts to sound like it could happen! The idea of a check from the government, once a month, covering our basic needs, sounds revolutionary…but remember, in 1935, when the U.S. government instituted Social Security, mailing out checks to millions of Americans once a month, that also sounded radical.

Some Useful Materials

The Black Plague pandemic and parallels to our Covid experiences.

Experts from The Economist discuss the past and future of work.

Economist Autor talks about the impact of Chat GPT and other AI on middle class jobs.

Autor on why human jobs increase and upgrade with automation, and the O-ring principle.

Wait–are we going to have a labor shortage?

Video on South Korea’s UBI experiment.

Podcast on UBI experiments around the world.

AI may diagnose patients better than doctors, says a small study.

A short but provocative column on whether we will be replaced by A.I.

A practical point-of-view on AI-proofing your job plans.

Media Attributions

- simon-kadula-8gr6bObQLOI-unsplash © Simon Kadula is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Office workers, 1920 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Office, 2020 © Israel Andrade