15 Investment: The Market for Loanable Funds Model and Alternatives

Bettina Berch

Consider this

If you search for images of investment, you’ll see stacks of coins, little plants being watered, or bar charts trending upwards. At least this photo seems to acknowledge that information–gotten from a newspaper, no less–might be necessary for successful investing! After reading this chapter, could you come up with a better sort of image?

In the last chapter, we focused on financial instruments, the actual vehicles of the investment marketplace. Now we are ready to get a little more abstract, by developing the economic model that explains some of the dynamics of the investment market–the market for loanable funds model.

The market for loanable funds

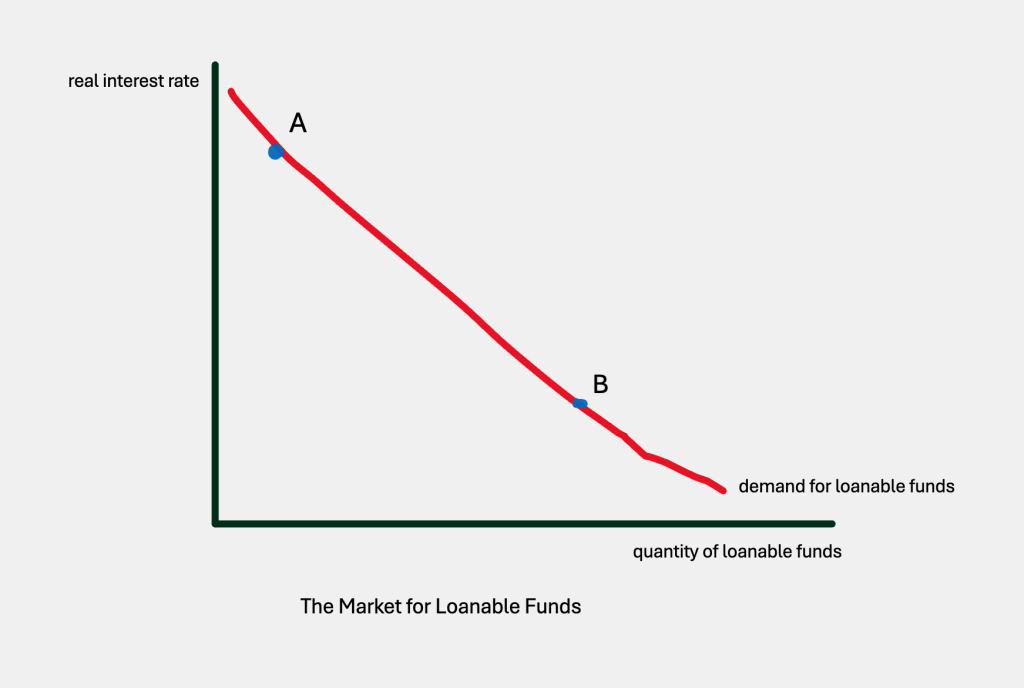

While this market doesn’t exactly exist in real life, it gives us insight into some basic dynamics of the economy at large. In this model, the price of borrowing money (the real interest rate) is related to the quantity of resources available for funding private investment (the quantity of loanable funds):

The demand for loanable funds comes from businesses wanting to borrow money and expand–it’s investment demand. When it’s expensive to borrow money (high real interest rate), there’s low demand for borrowing (point A). When it’s cheap to borrow money (low real interest rate), there will be a lot of demand for funds (point B). This is essentially defining a downward-sloping demand curve.

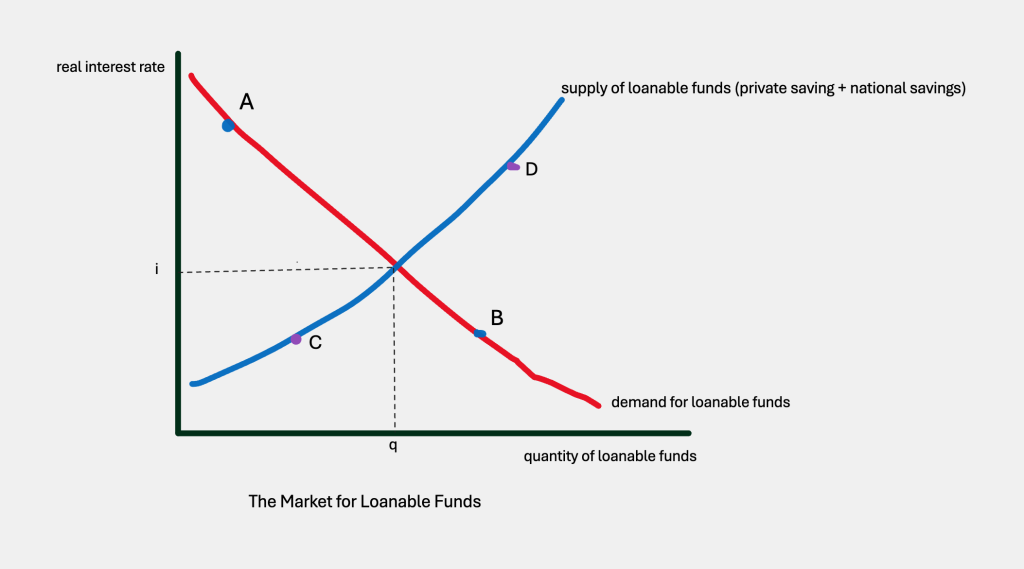

The supply of loanable funds comes from two areas–government or national savings (defined as government revenues minus government spending) plus private savings (what you and I have left after we are done spending). How does the amount of savings we generate, relate to the interest rate? Think of it like this: if the banks are offering you 10% interest on a savings deposit, won’t you think about the extra dollars in your checking account that aren’t earning anything? The spare coins under the sofa cushion? When interest rates are high, you mobilize as large a quantity of loanable funds as possible (point D). When interest rates are close to zero, can you really be bothered taking the spare change to the bank? Probably not, so low interest rates will result in a low quantity of loanable funds (point C).

The demand and supply curves together will determine some real interest rate (i) and some quantity of loanable funds (q) in the economy. Now let’s use this model! Let’s see what happens when policy-makers get involved…

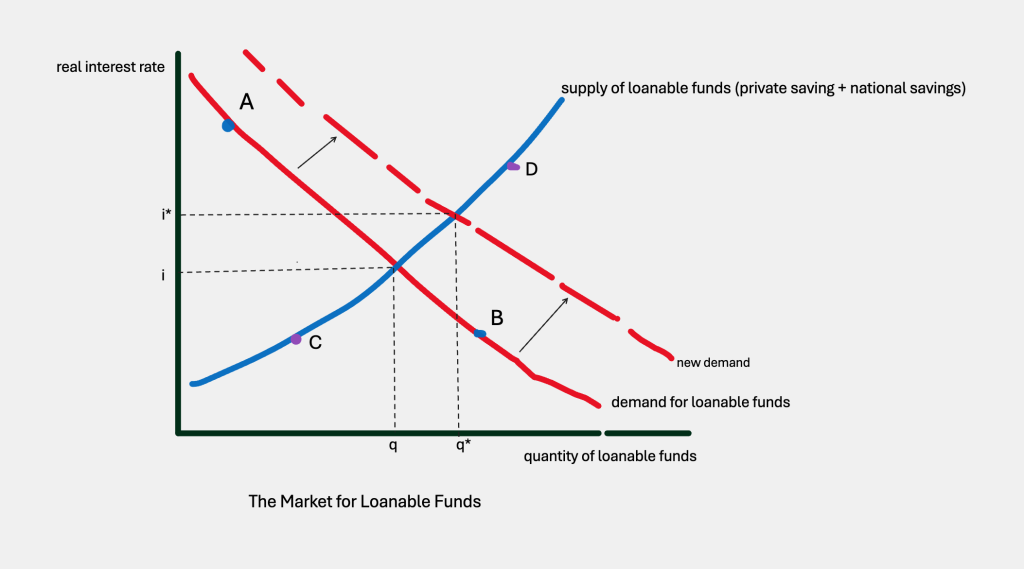

Congress offers business community a tax credit to use greener technology!

You could imagine Congress offering a 10-year tax break for businesses that go green, right? What would that look like for our loanable funds market? Other things equal, you could imagine businesses wanting to borrow more, at any given interest rate! This would shift our demand curve upwards, or to the right:

This will result in a higher real interest rate, i*, and a greater quantity of loanable funds available, q*.

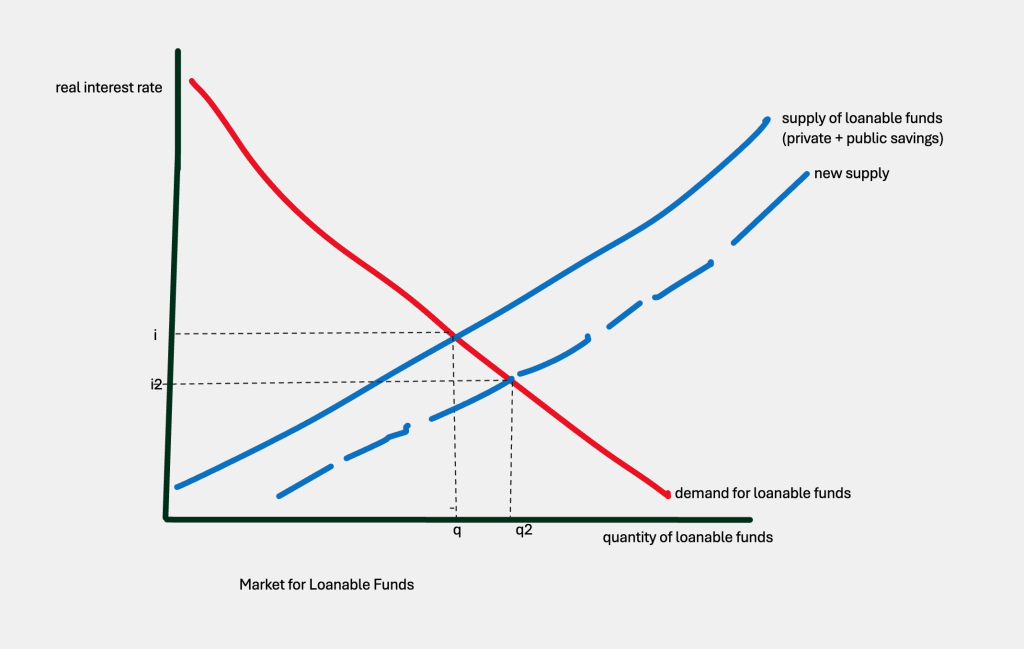

What if–instead– Congress says people don’t have to pay taxes on their savings anymore?

Normally, people pay income taxes on the interest they receive on their savings, which reduces its return. So imagine if Congress said we’re cancelling that tax! From now on, whatever interest you get, is tax-free! That would make any amount you saved, more valuable. You’d try to save more, which means a shift of our supply curve downward or to the right:

Our new real interest rate would be lower, at i2, with a greater quantity available (q2).

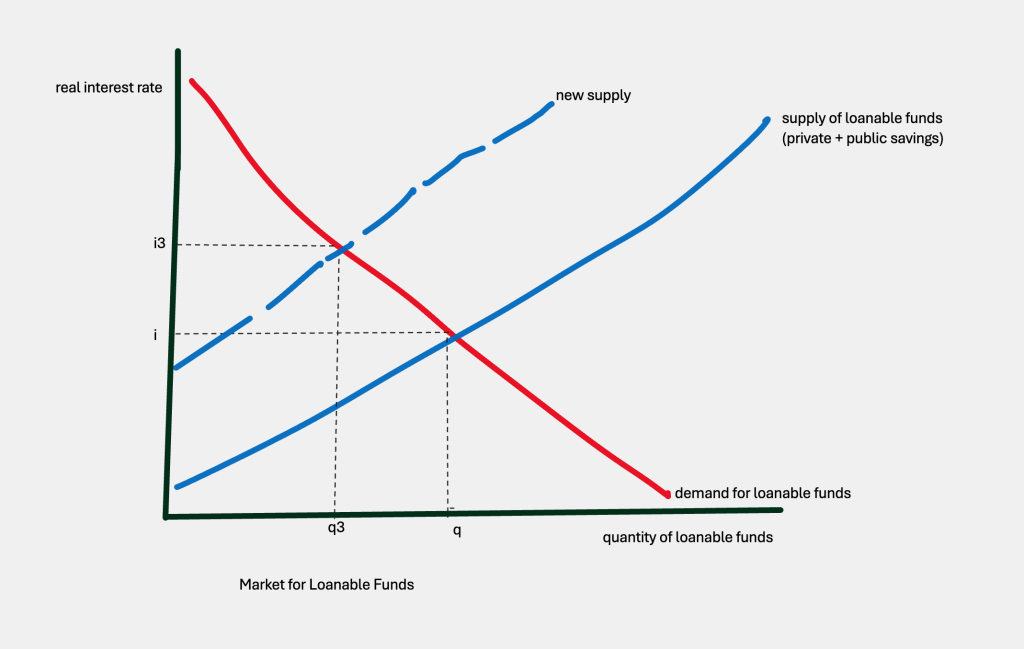

What if the government starts running a budget deficit (or a bigger one than ever before)?

Remember how we defined government savings: government revenue – government spending. When government spending is less than its revenue, it has a budget surplus, which here we call public savings. When government spending is more than its revenue, it has a budget deficit, so public savings are negative. Negative savings will shift the supply of loanable funds curve upward or to the left, resulting in a higher real interest rate (i3) and a lower quantity of loanable funds (q3):

While most economists agree that government deficits will push up interest rates, some emphasize a slightly different mechanism, highlighting the fact that government will need to borrow to finance that deficit. Increased government demand for loanable funds will shift the demand for loanable funds curve upward, or to the right. Either way, real interest rates are pushed up.

What we have seen with the loanable funds model, is a relationship between the real interest rate and the amount of funds available for investment–at a very abstract level. We need to get back to real life!

Real world alternative investment methods

If you’re a student–or someone helping a student–you know that in the United States, tuition and fees at even non-elite institutions can saddle a graduate with crushing debt for decades. The average student’s debt from private loans is over $50,000, and while there are movements for debt relief, they have not had overall success. Many Scandinavian countries, like Denmark, Sweden and Norway, offer free college education, in some cases, for international students.

Many students entering American universities are young and lack experience with major debt. They’re just happy to have ‘gotten in,’ and perfectly willing to postpone worrying about the bill until after they graduate. Debt and default may twist their career decisions, negatively impacting productivity, as well as mental health. What could be done?

Income-share agreements (ISAs)

Income-share agreements were tried out in various forms for years, but in 2016 Purdue University decided to try them as a substitute for student loans. If you think about it, borrowing for tuition with a student loan is like issuing a bond–you get a chunk of money from the lender that you pay back with interest after you graduate. What about dropping the bond model, and trying the stock model? Suppose when Purdue University accepted your application, they also offered to finance your education by buying stock in your future earnings: something like, “after you graduate Purdue, you pay us 15% of your future earnings for 8 years.” That’s the principle–the university (or other funder) paying your tuition in return for a share of your future earnings.

There are more details of course. Students going into high-paying fields–pre-med, STEM– would have to have a lower payback percentage than art history majors, or it would be unfair to the high-earners. People who took off time from the labor force would have to be able to stop their repayment clock. These provisions are not dealbreakers. The big advantages of ISAs are that students graduate with a manageable debt burden, and schools have an incentive not to offer worthless degrees.

Savings/investment outside traditional banks

Not everyone in the United States can qualify for a bank account. While in 2021, the percentage of Americans who were unbanked reached a new low of 4.5%, that’s still a lot of people, and it probably misses many. With the consolidation of big banks and the failure of small ones, many rural areas and towns don’t have a bank anymore, forcing people to drive long distances to obtain bank services. On the other hand, even small communities usually have a post office branch. Why not revive post office banking, like we had before 1967? Nowadays, if you don’t have a bank account, you have to go to a check-cashing business, wait in long lines and pay high fees, just to take care of your monthly bills or buy money orders. Maybe America’s big banks are not crazy for the revival of postal banking, but a lot of low income people would save a lot of money and time.

Another savings institution favored in some immigrant communities is the susu, or savings club. Members of a savings club meet regularly, putting a fixed amount of money in the pot each meeting. Each meeting, one member takes home the whole pot, in turn, until everyone has gotten a payout. The members–usually women–are bound by mutual trust, so they don’t quit as soon as they’ve gotten a payout. They incur no bank fees or bank paperwork. On the other hand, they build no credit history in the formal banking world, so they’re out of luck when they want to get a mortgage or a big loan.

When economists study ‘informal finance,’ they also find many people use a money guard, a trusted person who holds their money for them. The money guard might ask why a person wants the money they’re safeguarding and discourage them from wasting it or getting scammed. Not only does this system of savings offer psychological counseling that banks don’t pretend to offer, they can be more flexible as well. As with the savings clubs, however, there’s no credit history built this way, which might be why households often combine formal and informal finance techniques.

A completely different model of investment: Islamic finance

Finally, let’s consider another approach to finance that’s radically different from anything based on the ‘model for loanable funds’: Islamic finance. [a caveat in advance: the author is not an expert on Islamic finance] All three Abrahamic religions–Judaism, Christianity, and Islam–are based on the Old Testament, which restricts the charging of interest almost completely. Over the centuries, only Islam has maintained a ban on charging interest on loans—in effect, setting a zero interest rate. So how do observant Muslims manage to buy homes, build office buildings and highways, if they can’t borrow money?

To begin with, Islamic law forbids certain activities altogether–gambling, eating unclean meat, usury, fraud, slander, etc–so none of these activities can be financed. Some of these restrictions can be important. Banks in the West are accustomed to loaning money to farmers planting crops, perhaps charging a premium since the future harvest outcome is risky. Such a loan should not be made by an Islamic bank, as it involves gambling on an uncertain outcome, a good harvest. Needless to say, derivatives would be forbidden! But buying a home or building an office tower could be ok.

Let’s say you wanted to buy a house but lacked funds. You could approach the bank and ask the bank to buy the home. You would pay the bank rent while living in the home over the course of the loan, plus a payment the bank would give to its funders. While this might appear identical to a traditional western mortgage, there are significant differences. With the bank as a partner, rather than a simple lender, the bank has a greater role insuring that the home or project is a worthwhile investment. Islamic banking is fundamentally asset-based–there’s an actual home or car or bridge involved. And there’s risk-sharing–if it’s a bad project, the bank and the borrower will both bear the cost.

Having excluded speculative loans, Islamic banks were relatively unaffected by the world financial crisis of 2008. Indeed, people argue that the ‘ethical banking’ dimension of Islamic finance is a concept that western banks should embrace, to regain the confidence/support of the general population.

Some Useful Materials

Watch a video on the market for loanable funds.

Watch a short video on crowding out.

Watch a short video on the basics of Islamic finance.

Listen/read transcript of podcast on setting up a bank in the U.S. with Islamic-compliant mortgages.

Read about Takaful insurance, an Islamic-complaint form of insurance.

Listen/read transcript of podcast on a new way of financing college tuition: income-share agreements.

Read about community-based group finance: Jeffrey Ashe, Backyard Bankers: Immigrants, Savings Clubs and the Pursuit of the American Dream.

Media Attributions

- adeolu-eletu-E7RLgUjjazc-unsplash

- loanable funds1 © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- loanable funds2 (1) © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- loanable funds3 © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- loanable funds market with supply shift © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- loanable funds market with gov’t deficit © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license