8 GDP: What It Is…And What It Isn’t

Bettina Berch

Consider this

Gross Domestic Product, or GDP, includes both goods and services. How many different sorts of goods and services can you spot in this photo?

So far, we’ve been learning some basic tools of economics that we might use in micro or macro—they’re so useful, they’re in every toolbox. Now, in part two, we want to take a macro focus, and analyze the economy as a whole. We want to see the big picture! We start by taking a deep dive into the basic concepts at play—things like GDP, CPI, employment, growth, financial instruments. We will use these, in part three, to build a model of the economy as a whole, so we can understand the policy tools that model has to offer.

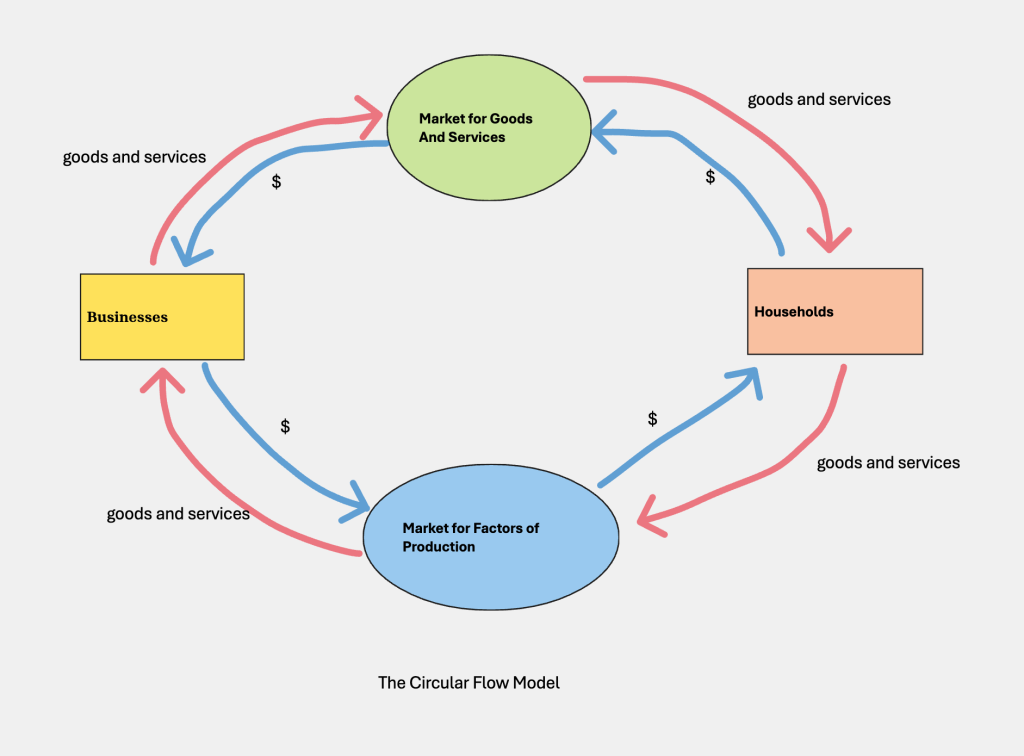

Remember earlier on, we looked at the Circular Flow model of the economy?

At the time, we emphasized how it showed the interconnection of households and businesses. Now we can focus on another feature of the model—the way one person’s spending was also another person’s income. Since income and spending are two sides of every transaction, they should be equal…which also means we could estimate the size of our economy by adding up all the spending in the economy, or all the income. They should both give us the same figure, more or less. Actually, we use both approaches in the U.S. national income accounts.

Before we add anything up, we have to make some decisions about what’s included.

GDP is the market value of ‘all’…

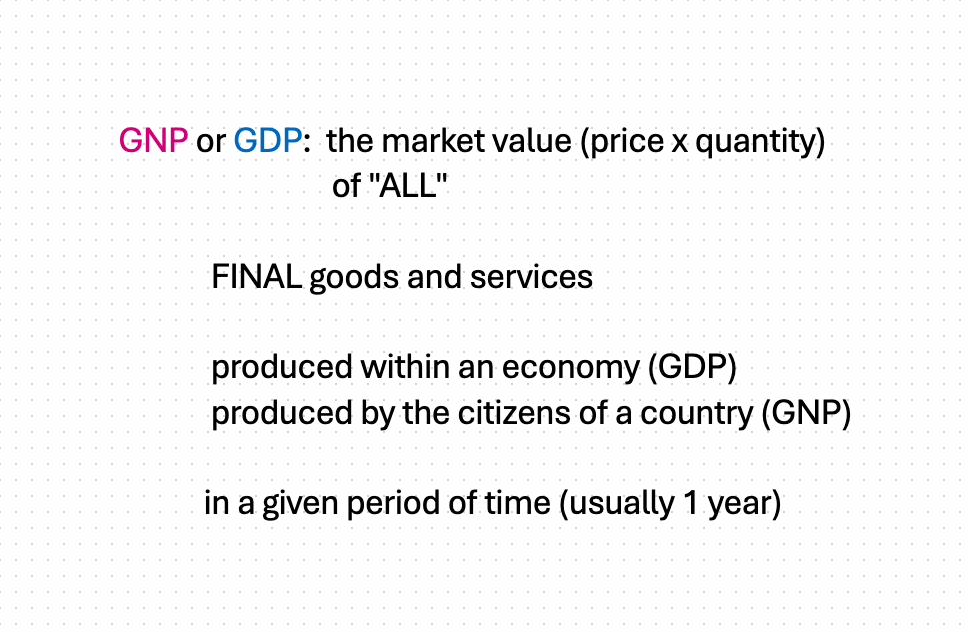

The basic definition of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is: the market value of all final goods and services produced within an economy in a given period of time, usually one year. Let’s break down that definition completely, so we know what’s really counted and what’s not. (Do you know that old saying, ‘if it’s not counted, it doesn’t count?’—think about it.)

The basic definition of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is: the market value of all final goods and services produced within an economy in a given period of time, usually one year. Let’s break down that definition completely, so we know what’s really counted and what’s not. (Do you know that old saying, ‘if it’s not counted, it doesn’t count?’—think about it.)

Start with market value. The opposite of this might be ‘personal value.’ We will value that really cute teddy bear at the price that’s on his ear, not by how much we absolutely love it. The same is true of things the economy produces that we think are really nasty, like cigars. You’d want to put a negative price on those, if you could. But if they’re produced by our economy, we price them at exactly their sticker price. We multiply those sticker prices of everything produced by our economy by the quantities sold [the sum of all (P x Q)s] and we get market value.

Or next problem is all. We would like to be finding the market value of all production, but we can’t. Consider types of work like gambling or prostitution or dealing illegal drugs. They are immensely rewarding (or why else would people risk jail to get involved) but we leave them out of the GDP accounting. Why? Imagine opening your front door to a person from the government wanting to know how many illegal drugs you’d bought last week. Your answer would be zero, correct? (Many states have recently begun selling recreational cannabis. They could get a low estimate of industry size pre-legalization from the revenues post-legalization, and retroactively adjust data. Admittedly, unlikely.) So we leave out these industries because we can’t get trustworthy statistics.

We leave out of the accounting things we make or do for ourselves. When I make dinner at home, that’s high quality production taking place, but none of my cheffy expertise enters GDP. If I bought the same meal at a restaurant, a lot of $ gets added to GDP. If I do my neighbor a favor and babysit her kids, that adds nothing to GDP. If my neighbor called an agency to hire someone, she’d be adding a lot to the GDP. You might argue that these are small amounts of money we’re discussing, but it can be an important point when we are looking at historical data. The twentieth century saw a big increase of women’s participation in the paid economy. When some women took paid jobs, they may have hired people to do housework and childcare, monetizing some of women’s previously unpaid work. Those paid caregivers and housecleaners added extra to GDP.

We also leave out of the accounting quality of life issues, which seem pretty hard to measure. But we know they’re there—just think of someplace you’d go for a vacation. That’s a place with a better quality of life than your day-to-day, none of which is reflected in GDP accounts. We also leave out of GDP the leisure we enjoy, even though leisure is a major normal good (your income increases and you want more of it).

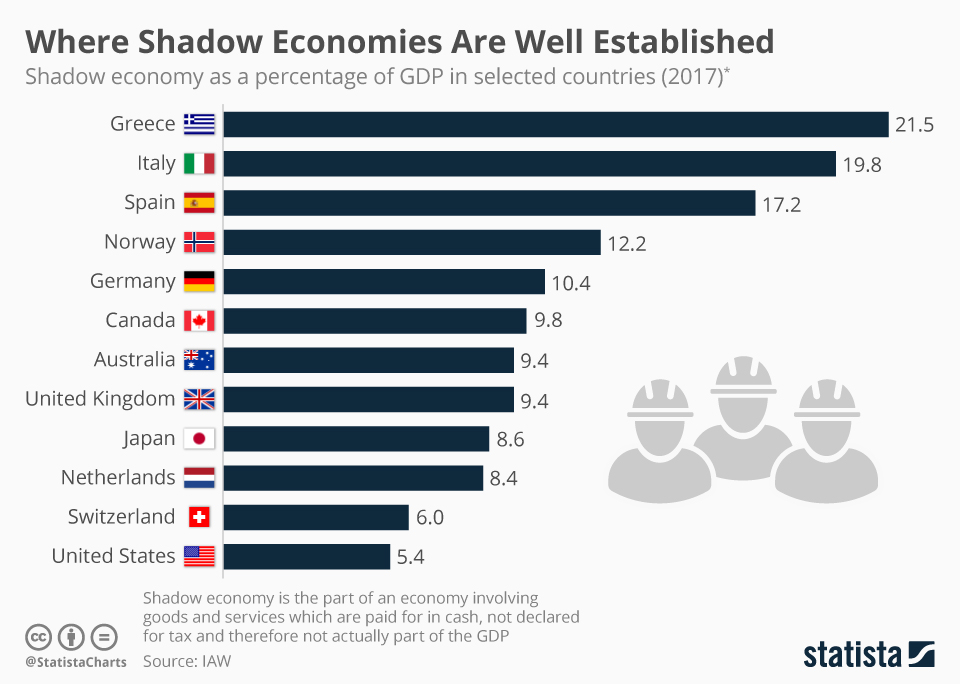

Another huge category we leave out of GDP is ‘off the books work,’ or the ‘shadow economy,’ the ‘informal economy,’ or the ‘underground economy.’ If you live in a big city in America, there’s probably a street or place where people gather to get hired for day labor. They’re paid cash at the end of the day, with no records kept. None of that labor is included in the GDP. People who’ve studied how much off-the-books work happens in different countries, have come up with some shocking figures. They estimate the proportion of ‘off the books’ work to all non-farm work is as high as 94% in Uganda, 74% in Guatemala, 73% in Honduras, and 54% in Mexico! Those examples make it sound like developed countries don’t have much ‘off the books’ work, but that’s not true at all.

Looking at Greece, Italy and Spain’s informal economies, they’re quite large. In fact, the United States is at the bottom of the chart, meaning we have a relatively small informal sector, compared to other countries. The larger the informal sector, the less tax revenues to the government, which means during natural disasters, for example, the government can’t help victims very much. We can notice that some governments with generous safety nets (Norway, Germany, Canada) have unexpectedly large informal sectors. Can you imagine why? (Tax rates have to be higher in countries covering a lot of social services. Anyone working ‘off the books’ avoids the high taxes but still gets the services.)

Finally, while it is true that the informal sector is larger in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America/Caribbean, the importance of the informal sector has steadily decreased all over the world.

…Final Goods and Services Produced within a Country in a Given Period of Time

Returning to our definition of GDP, we have seen there’s a lot we leave out, even if we say it’s the market value of all goods and services. When we say goods, we refer to durable goods (tables, fridge, rug) and nondurable goods (my breakfast coffee, the carton of milk). Services refers to value delivered in the doing—my teaching, your doctoring, lawyering, child care services, etc. But we only count final goods, not intermediate goods. Intermediate goods are items like seatbelts. All the output of seatbelt factories is used by car factories, where those seatbelts are installed in cars that are sold for a sticker prices that includes the value of the already-installed seatbelt. If we added to GDP the output of the seatbelt factory and the output of the car factory, we’d be double-counting the value of seatbelt production.

When we add up all the output produced within a country’s borders, it’s GDP, gross domestic product. (The root of domestic is ‘domus,’ or home, so, the home borders.) If we add up all the output of the citizens of a country, no matter where in the world they are producing it, that’s GNP, gross national product. (It’s the product of ‘nationals,’ or citizens.) We use both of these measures (and more, GDI, NNP, etc) because they measure different things, so one might be more useful than the other, especially in more advanced courses. For our purposes, it’s enough to know what each term means.

We are measuring the GDP or the GNP for a given period of time, usually a year. And it’s the year the good or service was produced. So if you go to some retro store and buy some cool (and expensive) Fifties sunglasses, that purchase does not go into this year’s GDP. Why not? Because those glasses were already counted in 1957 when they were produced. Adding them in again, would be double-counting them. Which means, for example, that a country embracing the ‘reuse-don’t waste’ way of life, might see a decline in GDP, even though people’s standard of living was holding up fine. What happens if something was produced this year, but isn’t selling? It’s considered an unplanned inventory investment.

So we’ve seen that the simple definition of GDP (the market value of all final goods and services produced within a country in a given period of time) is not so simple to get right—and there are more issues ahead. Before we go there, let’s stop looking at GDP from the statistical point of view, and see it as economists do.

The Components of GDP

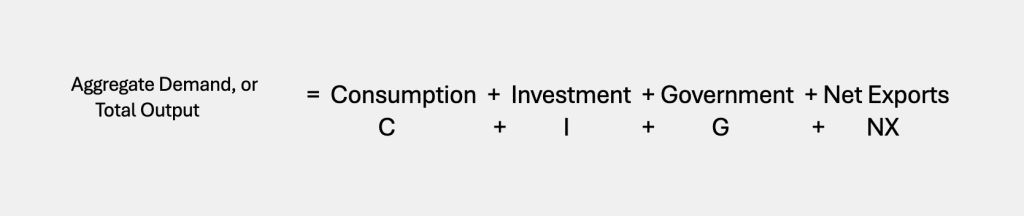

To break down GDP into categories, economists have found it most useful to do it like this:

Y is the output of the whole economy, or GDP. C is your consumption, what you buy. Investment is business spending to buy capital goods, or a consumer commissioning the building of a new home—both are activities that produce a value stream over many years into the future. Notice that among economists, investment means something different than it does on the street, where your friend might tell you to invest in some Apple stock. To economists, buying Apple stock is a financial transaction, not Investment. G is government spending (local, state, federal). NX is exports (X) minus imports (M). (These particular letters are standard in economics, so you may as well learn them now.) By breaking down GDP this way, we can focus, later on, on how each of these parties reacts to changes in the price level in our economy. Right now, it’s enough to know what they are.

If we look at actual data on the U.S. economy in the chart below, we can see the actual size of each component. C (Consumption) is huge at 68%. I (Investment) is 18% and G(Government) is 17%, roughly similar in size. And NX (Net Exports) is -3%–which means we import more than we export. Up until the mid-20th century, the U.S. was a net exporter. We will think about that further when we get to the international trade chapter later in the book, so hold that thought!

Adding up all the components of the U.S. GDP, as of the end of 2023, it comes to around $28 trillion dollars…and I don’t even know how to think about that number. Is it large? As large as it should be?

We need some tools to evaluate our GDP numbers.

Some Useful Materials

Listen to a podcast on the invention of the GDP.

Watch a great video on real versus nominal GDP.

Media Attributions

- Harlem street scene © Berenice Abbott is licensed under a Public Domain license

- circular flow © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- GDP definition © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- components of agg demand © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- GDP categories © Bureau of Economic Analysis, Department of Commerce is licensed under a Public Domain license

- U.S. GDP components © U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis is licensed under a Public Domain license