18 Monetary Policy and Inflation

Bettina Berch

Consider this

The German hyper-inflation of 1922-1923 meant German marks were so worthless, children made kites with them! People used them to light their stoves. Could you ever see yourself setting fire to money?

We have seen that the Federal Reserve, our central bank, both regulates the banking system and sets monetary policy. If it decides that the economy needs stimulating, it may increase the money supply/ lower interest rates. If it believes the economy is over-heated, it may contract the money supply/ raise interest rates. You may be wondering, what difference does the size of the money supply make?

Introducing the ‘nightmare world’ and the ‘fantasy world,’ our way of talking about the price level

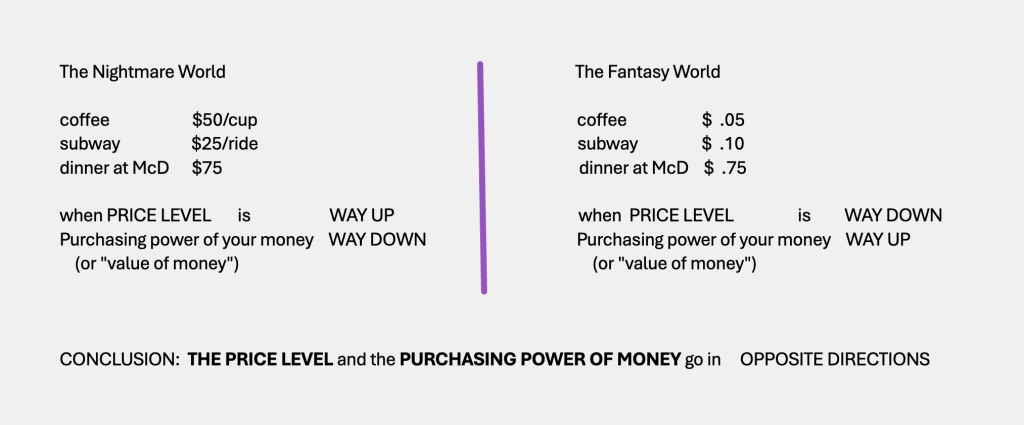

Instead of using more technical language, when we refer to an economy with a very high price level, we’ll call that the ‘nightmare world,’ since for most of us, the thought of walking around in a world with $50 cups of coffee and $25 subway rides is a nightmare! Likewise, we’ll call an economy with a very low price level a ‘fantasy world,’ since for many of us, the thought of walking around and finding coffee for a nickel and subway rides for a dime would be a dream! We’d feel so rich! So we’ll use nightmare and fantasy worlds, from now on, so we can understand more easily how we’d react to living in each of these worlds.

How your demand for money changes depending on which world you enter

On a normal day, you might check your wallet before leaving your apartment and make sure you had a $20 to cover your cash needs for the day.

But let’s imagine you left your apartment tomorrow and discovered you had entered the nightmare world of high prices! Your coffee stand at the corner was charging $50 a cup! The subway had a big sign announcing it was charging $25 for a ride! The McDonald’s nearby was showing $75 for a meal! This was all very strange and disturbing–but you knew you had to go back to your apartment and get more cash–a mere $20 wasn’t going to get you through this nightmare world.

Or, let’s try another scenario. You get up, you check that you’ve got $20 in your wallet and you go out…into the fantasy world! Coffee is a nickel! The subway costs a dime! Dinner at McDonald’s seems to cost 75 cents! Before you start running around, you realize you really don’t need that $20 in your wallet. You go back inside and switch it out for a $5.

In the nightmare world, with the high price level, the purchasing power–or the value– of your customary $20 bill is so low, you need to go get more cash. In the fantasy world, with a low price level, the purchasing power–or value–of your customary $20 bill is so high that you’d decide you need less cash. In other words, in the nightmare world, the purchasing power of your money is so low that your demand for it is high. In the fantasy world, the purchasing power of your money is so high that your demand for money is low.

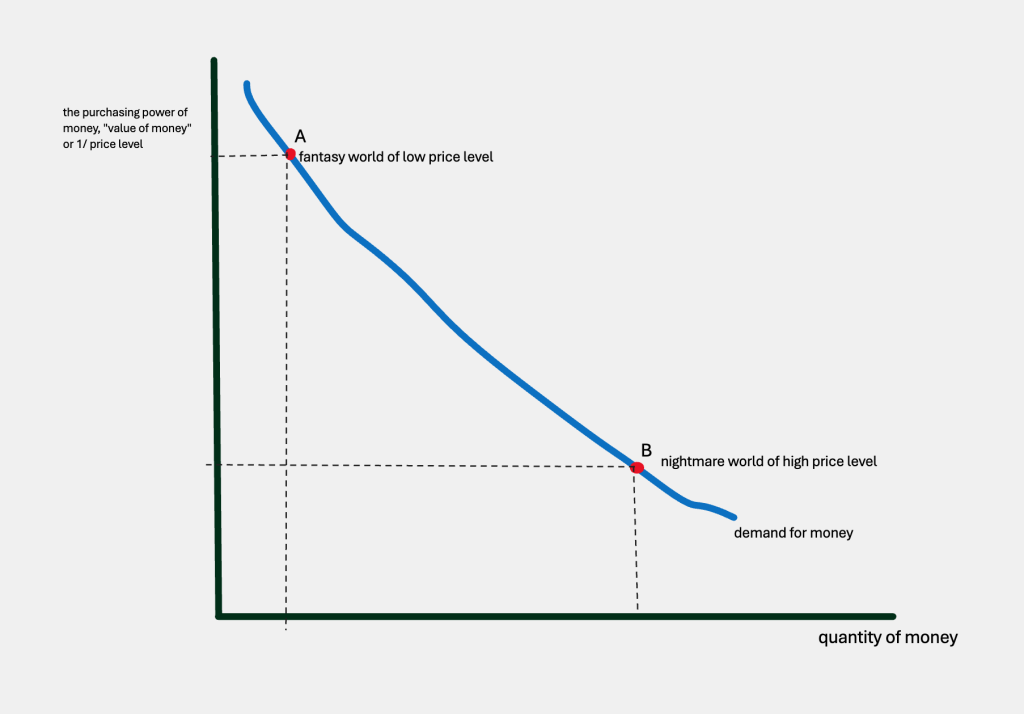

We are describing a demand for money curve, determined by Point A, the fantasy world where the purchasing power of money is high, so you demand less, and point B, the nightmare world point, where the purchasing power of money is low, so you demand a lot of it:

Add a supply curve and see what happens!

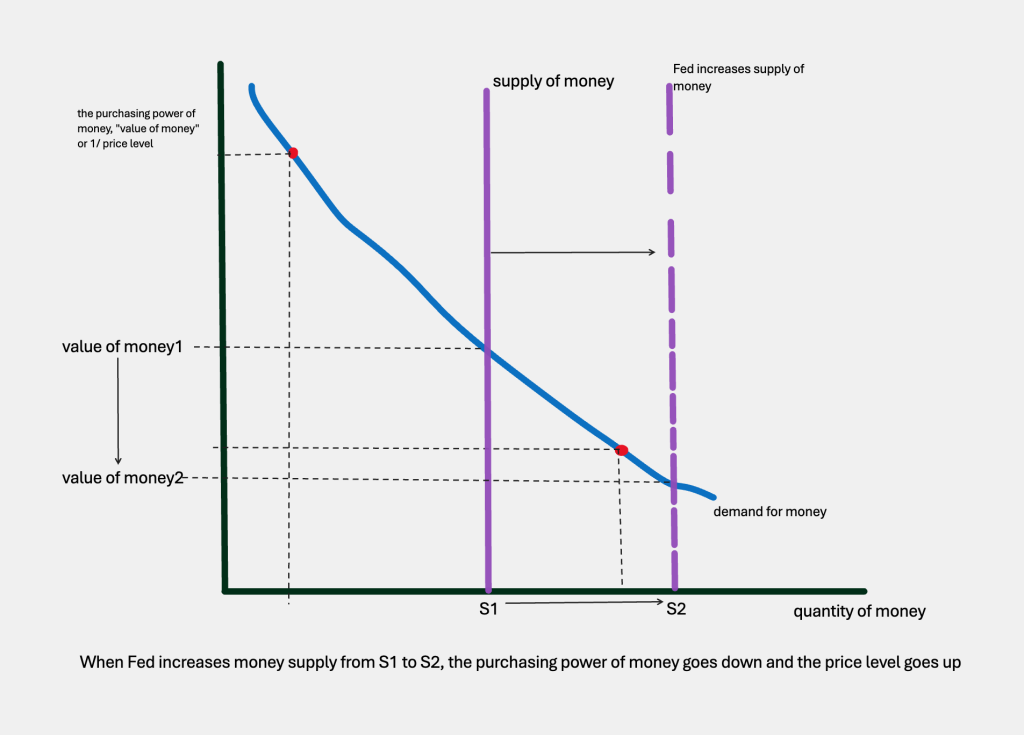

As we determined in the last chapter, the supply of money is set by the Federal Reserve. They have their target quantity–some spot on that quantity of money axis– and they use their tools to make that happen. Likewise, they can use their tools to, let’s say, increase the money supply. Let’s see what impact that has:

As we can see, if they increase the size of the money supply from S1 to S2, this will result in a fall in the purchasing power of money, or the value of money, from V1 to V2. What is the meaning of this in real life? In exaggerated form it’s something like this cartoon from the hyper-inflation of Germany in the 1920s:

When the central bank increases the money supply, it drives down the purchasing power of money! That paper money buys less and less stuff, until you end up using it to light your stove. And this is the point of view of the classical economists. For them, if the central bank increased the money supply, it just pushed up the prices on everything. It changed nominal prices—it did not change anything real. Our classical economists saw money as a sort of veil covering the real economy–changes in the money supply just changed the price level, but didn’t impact the amount of real goods and services an economy produced.

Try understanding this Money Veil concept a simpler way

This sounds a bit abstract, so a simple example might help. Have you ever played the board game Monopoly? The outer rim of the board is lined with various properties you can purchase at fixed prices if you land on them. After you buy a property, if someone else lands on it, they pay you a fixed ‘rent,’ like $100. Before starting the game, each player is dealt $1500 of paper money from the treasury. Each player throws the dice and advances on the board according to the throw. It’s a lot of fun.

But let’s suppose you start playing with your grandma’s Monopoly set, a set that’s been used by generations of family members before you. They lost a lot of the original paper money under the sofa and who knows where! Right now, all that’s left for each player is $100 to start the game. After one or two throws of the dice, a problem comes up. To buy most properties, you need $100 or more. Boardwalk is $400. After buying maybe one or two properties, everyone is out of cash and can’t buy much of anything. The game isn’t fun anymore, since you’re just rolling the dice and moving pieces without buying or renting, which was the fun part.

Now–since you’ve taken economics–you propose a solution! You say, let’s start over, with everyone getting their initial $100 stake, but let’s reprice all the properties on the board–take a zero off the prices. Buy Baltic Avenue for $6 instead of the previous $60, and so on. Now the game is fun again, since people can buy properties and charge others rent and try to win. By reducing the nominal prices on properties, you restored the relationship between the quantity of money in circulation and the price level. The classical economists would have approved!

Inflation isn’t just a board game: some people lose

When you confront higher prices in the grocery store on things you buy every visit, or at the gas station, it’s an ‘in your face’ experience. You don’t stand there and calculate how much your wages might have increased at the same time (and maybe they haven’t). Inflation is never popular. But it can be damaging to some people more than others–and to economic productivity overall. Let’s look at a few of these cases.

Do you tuck away cash in a special place–like a book on your shelf or under your mattress? Your cash savings are losing purchasing power during inflationary periods. If it’s just loose change in your piggy bank, it’s not big deal. But many people living in unstable countries horde dollars–so if the U.S. has an inflationary period, those savings are losing their purchasing power. Any assets that are stated in nominal terms (your granddad’s $10,000 life insurance policy) lose value during inflation.

Do you work at a minimum wage job? The various minimum wages are stated in nominal terms. The Federal minimum wage was set at $7.25 an hour in 2009 (that’s a nominal figure, because it is stated in dollars and cents that don’t adjust to changes in purchasing power), for most categories of workers. Does $7.25 an hour still buy as much (or as little) in 2024 as it did in 2009? No! Anyone working for a nominal wage that isn’t tied to a cost of living clause, will be losing purchasing power when there’s inflation in the overall economy.

Inflation imposes costs on the economy overall

If an economy is experiencing high inflation rates, people start adjusting. If you get paid every Friday, you–and many others–might cash that paycheck right away and go shopping, to convert that money into goods, before it loses even more purchasing power. A lot of your time and mental energy may be used up, just plotting how to use that cash wisely. Economists sometimes call this ‘shoe leather costs,’ picturing you running around to shops. More than the wear and tear on your shoes, inflation may be taking a toll on your productivity at work.

Another productivity drain are the mixed signals that inflation sends to producers. Suppose you run a factory making high end furniture. All around you, you see the prices on good furniture rising. Normally, you’d think–there’s more demand for furniture, so prices are rising, so I should expand my factory! But what if higher prices on furniture are just reflecting a higher price level in the economy as a whole, i.e., inflation? In an inflationary period, producers have a hard time interpreting the signals they’re getting from market prices. Is there higher demand for my product, so I should produce more? Or is it just the inflation in the economy as a whole, so I shouldn’t expand output?

What about deflation? Good or Bad?

Deflation is the opposite of inflation, so it means the price level of everything in the economy is falling–groceries, fridges, cars, wages, rents, etc. Often, people imagine it would be fantastic to live in an economy with prices always falling on everything! But let’s take a closer look. Suppose you lived and worked in Japan in the late 1980s, and you decided to get a 30-year mortgage and buy an apartment. The apartment cost the equivalent of $300,000. You signed a contract with the bank to pay them $1000/month for the money you borrowed on your mortgage. You did not know that Japan would enter a long-running deflation starting in the 1990s. By the year 2000, what is your situation? Your wages have been falling for a decade–that’s part of deflation. But you still owe the bank $1000/month because your mortgage is fixed in nominal terms–and it’s getting harder and harder for you to scrape together $1000/month, when your wages are falling. Even worse, apartment like yours aren’t selling for $300,000 anymore–they’ve gone down in price like everything else. You’re stuck.

The deflation problem is bigger than your mortgage. Let’s think about the economy as a whole. Suppose our economy suddenly fell into deflation, so prices were falling all around you, and everyone was talking about it. Let’s say you moved into a new apartment and you wanted some new furniture too. So you go shopping at the department store, you look at everything, try out all the cool sofas, and then—nothing! you say to yourself, ‘I like that sofa, but next week, it’ll be 10% cheaper.’ Everybody’s looking, but no one’s buying! Of course, if it’s necessities–diapers for the baby, aspirin for your headache–people will buy now. But for other things, ‘deferred consumption’ might be everyone’s answer. How does that impact the economy? If everyone is just testing the sofas, but no one’s buying, the shopkeeper will start laying off staff. Laid-off people will have less money to spend, reinforcing the low consumption trend. The cycle can keep repeating, causing the economy to shrink.

Coping with changes in the price level

Most of the problems that inflation or deflation cause for average people can be mitigated. Let’s take grandma, living on her social security check every month. Based on the contributions she made during her working years, she knows that this year, she will get a check every month for, say, $1500. Maybe in January and February, that covers her basics, but if inflation is raging, $1500 won’t buy her much by April. However–by November, Congress will look at what has happened to the cost of living index (our old friend, the CPI) and decide that next year, social security payments might rise by 5%, for example, in the new year. It’s after-the-fact, so grandma’s always trying to catch up with changes in the purchasing power of her social security–but at least it happens.

Other people have ‘cost of living adjustments’ (COLAs) written into their union wage agreements, or other payment contracts. If you have a mortgage, it may be an ‘adjustable rate mortgage’ (ARM) that charges you a higher or lower rate depending on the movement of interest rates in the economy. Or, on the reverse side of things, you might sign a contract locking you into a particular rate–for gas or electricity, for example–so that even if the market price goes up, you charged the price you contracted for, for the length of the contract. Since no one can predict the future, COLAs and ARMs are more common than fixed-rate future contracts, but it also depends on the type of business you’re in.

Bottom line? Economists prefer inflation rates below 2%. Inflation above 4%, economists start talking about tools to address the situation. Deflation makes everyone extremely nervous, in part because we’ve had very little experience correcting it successfully. But let’s take a break from reality for a moment, and think about the future of money. What kind of money will we be using in another decade or two? Will we still have Federal Reserve notes in our wallets?

Some Useful Materials

Watch a video about Japan’s deflation experience.

Watch a video on Venezuela’s hyper-inflation.

Read about the deflation threatening China’s economy.

Listen to an anti-inflation reggae song from the Jamaica Central Bank.

Read about Hyper-Inflation in Zimbabwe.

Watch a short video about how the Fed decided on a 2% inflation target.

Media Attributions

- German HyperInflation is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Purchasing Power of Money and Price Level go in Opposite Directions © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- demand for money © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Supply of money shift © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Gutenberg-und-die-Milliardenpressse-1922–(Jg–27)-Heft-33-Seite-469 is licensed under a Public Domain license