6 Roles of the Government in the Economy: Market Failures (Public Goods and Externalities) and the Criminal Justice System

Bettina Berch

Consider this

Whenever economists try to explain a ‘public good,’ they almost always use the example of the lighthouse, even though most of us have rarely seen one. We probably know next to nothing about how they work. Can you see why the lighthouse has become the ‘poster child’ for a public good?

Price controls set by the government can be controversial, because they favor some and harm others. Even worse, you can’t argue that they make markets more efficient–because they don’t! Sometimes they mess things up. The people you wanted to help, can end up unemployed. Landlords can feel free to discriminate against potential renters. But don’t lose hope—there are ways the government can intervene in the economy that improve market efficiency. When the free market produces too much or too little of something, we call this a market failure, and these situations can be fixed when government steps in. We will discuss two important situations of market failure—when we have public goods, and when we have externalities.

Public Goods

What do lighthouses, AM-FM radio, and toll roads have in common? They are all varieties of public goods. A public good is something a lot of people might want, but no one’s willing to provide, because they know the outcome: ‘Once I provide it, everyone’s going to use it and no one’s going to pay!’ In economics, we have a special term for freeloaders. We call them “free riders.” Imagine we’re a city by the sea and we decide to build a lighthouse to mark the dangerous sections of the coastline, something that people have been doing from ancient history to modern times. Lighthouses are expensive to build, and once they’re there, many benefit from them. And they benefit quietly, by not crashing their boats on the rocks. Is there any way the builder of a lighthouse could charge any of these users? No, they’re “free riders.”

Another example—AM-FM radio. We can all turn on the radio and listen to whatever station we want, and no one can charge us for the pleasure, we’re “free riders.” You might argue, that programming on most stations is paid for by the advertisers, so the market has found a solution. But what about “public radio,” where there’s no advertising (but a lot of begging during pledge drives)? Likewise, you could consider “the internet” a public good. Like lighthouses–and Wikipedia, perhaps–we need government to provide these desirable products, since once they’re available, there’s a world of free riders.

The military of a country is another public good—once it’s standing, it protects everyone, even those who aren’t paying for it. Basic research on the origins of the solar system is a hugely expensive public good, which benefits many businesses doing more applied, commercial projects. No one company could justify spending billions on the Big Bang, even though they do pay to have pharmaceutical experiments shot into space. All over the economy, we have projects that the government needs to fund because they are desirable, but they have a “free rider” aspect that makes it hard for private enterprise to supply the product through the marketplace.

How do economists describe the special features of a public good? We say it is a good that is non-rivalrous and non-excludable. Non-excludable is easy to understand —you turn on your radio when you please, and orient your ship by that lighthouse when you pass. No one can exclude you; no one can stop you from using that thing once it’s been provided. Non-rivalrous is trickier—it means that just because I am using it, doesn’t prevent you from using it too. I can go enjoy the park today, and so can you. When you think about it, most market products are rivalrous—if I buy that particular necklace, you can’t. Public goods are largely non-rivalrous.

In the world of public goods, things are rarely pure. Some public goods can be non-rivalrous but also excludable, like a toll road— you can be kept off that road if you don’t pay the toll. Some public goods can be non-excludable but also rivalrous, like if I go camping and I scavenge all the twigs and fallen branches for my bonfire. They were available to all (non-excludable) but when I gathered and burned them no one else could use them (rivalrous).

Once you get the flavor of public goods—that we can all use them once they’re here (non-excludable), and my using them doesn’t prevent you from using them too (non-rivalrous)—it’s no mystery what a headache they become for a market economy, where everything is supposed to be excludable and rivalrous for the market to provide the optimum amount of that thing. In that light, you can understand why so many things have been moved from public goods to private goods. Consider radio stations…and the rise of subscription radio like Sirius XM, which is only available to customers who have paid for it. Consider the British Enclosures laws in the 1700s, designed to turn public grazing land into private “enclosed” areas for the landlords’ livestock.

The bottom line with public goods is that if we left them to the free market, we wouldn’t get them, or we wouldn’t get enough of them. We need government (aka the will of voters) to decide an appropriate quantity and to provide the financing.

Externalities: what they are

An externality refers to a gap between private costs or benefits (the focus of market participants) and social costs or benefits (which markets usually ignore). Imagine I own a frisbee factory in Hackensack, New Jersey. I make a good profit producing these frisbees, especially since I can easily dump all our toxic sludge (a by-product of plastics production) into the handy Hackensack River. I can ignore the pollution I create, but people in the towns downriver can’t use the river anymore. To me, doing my private cost calculus, that sludge is a non-issue. It’s outside my concern. It’s an “externality.” My private production costs are less than the social production costs.

Consider some real life examples. In 2020, the ferry company, New York Waterway, was accused of emptying ferry toilets directly into the Hudson River, instead of using a more expensive, environmentally-safe disposal system. Try a global example—climate change. While there are ‘green’ businesses out there, most are not. Factories small and large continue to emit globe-warming carbons, because it’s cheaper for their own company than using greener technologies. The costs imposed on the planet are external to their private cost calculus.

Externalities can be non-monetary as well—like the guy in the apartment next door, who practices his clarinet (badly), just when you needed a quiet evening to get some work done. The fact that you can’t work is a cost he imposes but doesn’t think about—for him, it’s external!

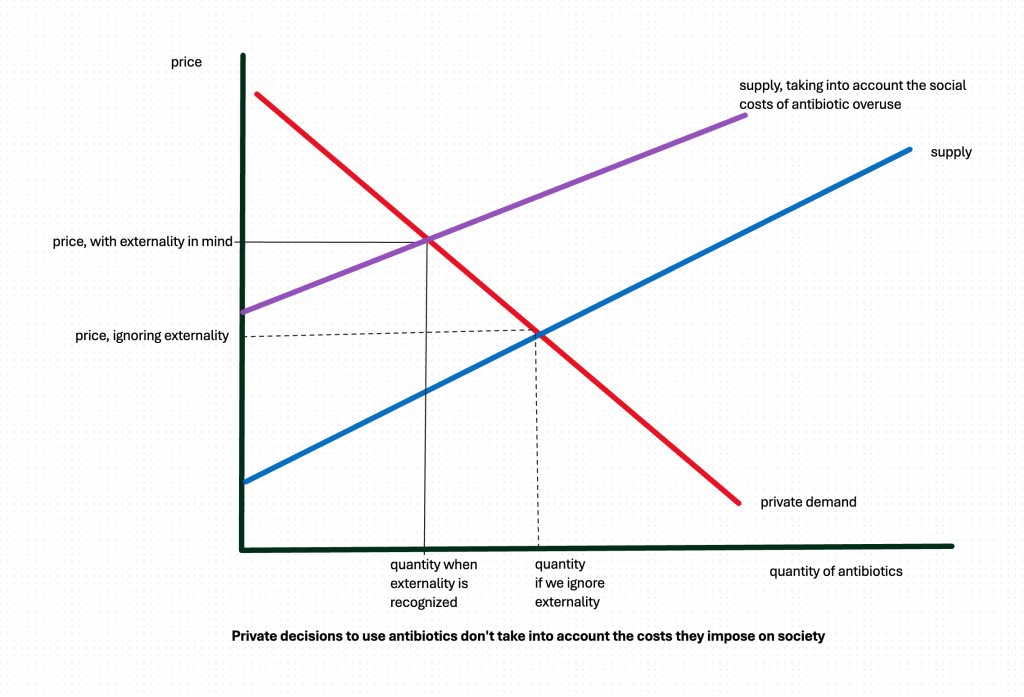

What all these negative externalities have in common, is that their social costs are higher than the private costs. Let’s take the example of antibiotic overuse, which is cancelling the effectiveness of antibiotics and leaving the world with fewer weapons against infection. A person who has a cough might ask for an antibiotics prescription, thinking it’s a cheap option that might be effective. The social cost of that prescription–weakened antibiotics effectiveness– is a lot higher. If we included these extra social costs in a more inclusive supply curve, the new curve would shift upward, or to the left:

Once the social costs are taken into account, market quantity goes down and price will be higher.

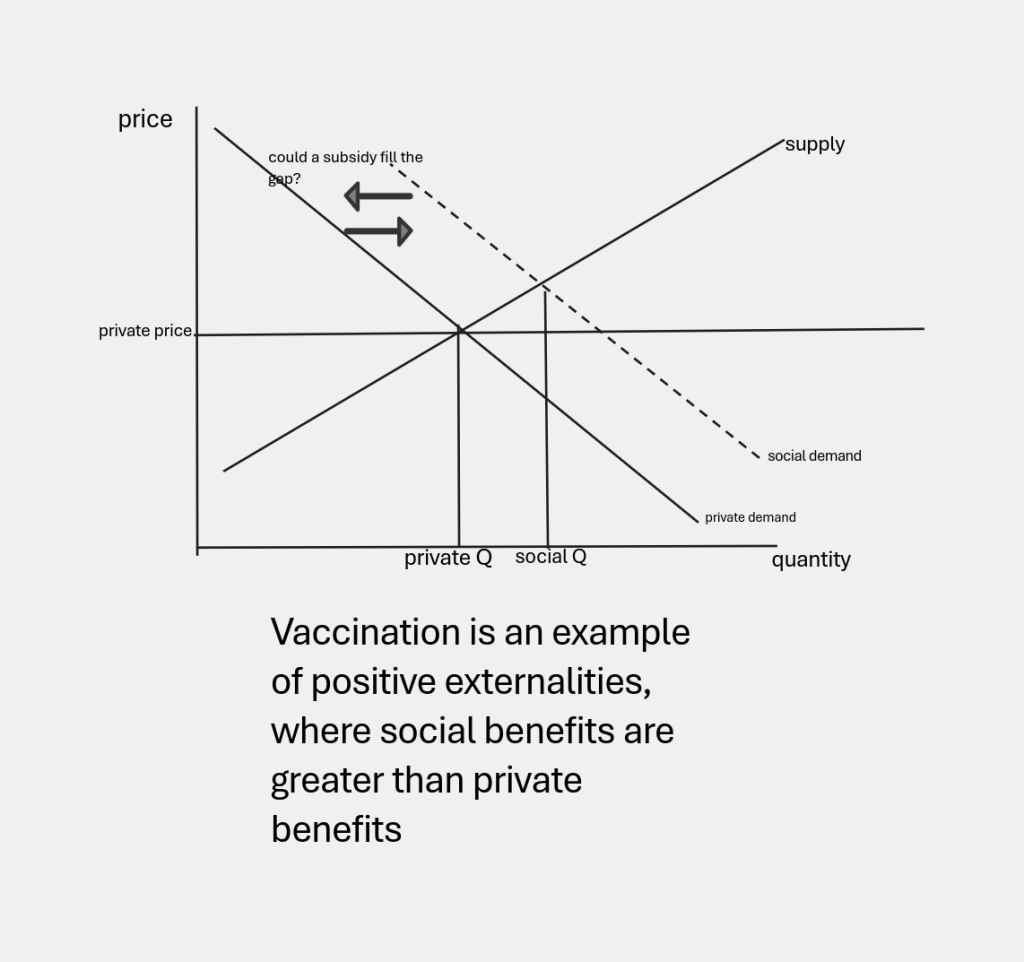

Not all externalities are negative, however. If I walk to work instead of driving, I get personal benefits (health, saving on care expenses) but I give benefits to society (less pollution, less traffic on the road) as well. If I walk instead of taking the subway there are positive externalities—less crowding on the subway trains. If I get a vaccine shot, there are benefits to me, but also benefits to the community around me. Thinking in terms of graphing it, when there’s a positive externality on the demand side (it’s a demand issue because we ‘consume’ a vaccine shot) we could see a shift of the demand curve upward, or to the right, when we include the social benefits.

Some externalities are either positive or negative depending who’s on the receiving end. If someone’s lip-syncing in the subway for spare change, it’s a positive or negative externality to me, depending on whether it’s Motown or not.

Externalities: how do we handle them so the optimal amount of a good or service is provided?

With externalities, the free market does not provide the optimal amount of the good or service. When we’re dealing with negative externalities in particular, people often look for government intervention. If it’s toxic sludge fouling our favorite rivers, we might want to pass a law banning that pollution outright. Or pass a law with big fines and jail time for offenders. If you’re a libertarian type, you might not like having more laws on people, so you might suggest a tax on polluters. A tax would supply a market incentive to stop bad behavior. Sounds like the way to go, right? Think twice. Let’s say we make the people buying gas-guzzling, pollution-dripping cars pay a huge purchase tax. That would stop most of us from buying those big polluters, right? But it won’t stop some very rich person from buying the polluting car, because ‘money’s no object’ to this guy. If we let the rich buy the right to ruin the environment, is that a positive outcome?

Let’s take a less catastrophic negative externality situation. What if it’s your next-door neighbor learning saxophone (badly) at dinnertime? In a situation like this, laws and taxes seem like overkill. Maybe I could bribe my neighbor not to practice when I’m home? Or he could pay me for the inconvenience I cause him? All this bribery sounds cold, but we could go lighter, like he could offer me some nice headphones?

When the government steps into a positive externalities situation, this is sometimes called industrial policy. Imagine a firm would have liked to provide chip production training for its workers, but the externality problem makes them change their mind. The training is expensive and the firm can’t capture the benefits of that training if those trained workers leave the firm and start their own company. When the government steps in and offers to pay the costs of worker training, the quantity of training increases, reflecting the real social benefit it is generating.

In the vaccine example above, the government could offer people some treats for getting a shot. New York City did this in July 2021, when the City offered people $100 to get a Covid vaccine at a city-run facility. And maybe New York decided to do this because a prominent conservative economist, Greg Mankiw, endorsed a plan in September 2020 to pay every American $1000 to get a Covid vaccine! (With what you know now, do you think that plan would have been a good use of our resources?)

With public goods we need the government to step into the economy and provide the good, regardless of how it’s financed. For goods with externalities, we need the government to push people towards providing (or consuming) more (or less) of the good.

Sometimes Goods and Services are Produced /Administered by the Government Itself: the Criminal Justice System

In some cases, a government goes beyond providing a single public good, and undertakes to run a whole industry themselves. Think of public schools, the U.S. Postal Service, and local,/state/federal detention systems (aka, the criminal justice system). Historically, some of these industries, like the mail or schools, were mostly government-run for a long time, until private sector competition (UPS, FedEx, charter schools) took hold.

The situation with the criminal justice system is more complicated—and more consequential. If you watch the film 13th (on Netflix or youtube ) you can learn about the slave origins of our mass incarceration situation today. Even today, the criminal justice system in many parts of the United States operates so-called “restitution centers” that keep the formerly incarcerated in a kind of indentured servant status for decades after their sentences were served, as reported by The Marshall Project. Sometimes LFO’s (“legal financial obligations”) keep people indebted for the rest of their lives. Hand in hand with the huge numbers of people of color incarcerated in America, has been the growth of private enterprise in the incarceration industries. Yes, we had private prisons in states like Louisiana before the Civil War. But the modern prison industry really got going in the 1980s, when companies like CoreCivic were offering lowball incarceration services to cash-strapped state legislatures or immigration detention authorities. The proportion of inmates in private prisons in America, relative to the total, keeps rising—it was 14% in 2020 (see this short but useful report.)

While you could argue that competition from UPS forced the U.S. Postal Service to be more efficient, or that charter schools have forced traditional public schools to improve, could you also say that private prison operators have forced the criminal justice system to improve? From the terrible state of U.S. prisons, it would be hard to argue that privatization has had a positive impact. The reasons may lie in the cost structure of incarceration. Providing low quality room and board is cheap. Providing prisoners with education and rehabilitation services so they can live successfully in the outside world after release, is expensive. Companies in the for-profit sector can low-bid by hiring less-qualified staff, passing the cost of expensive services (medical, for instance) to prisoners, and eliminating expensive rehab training.

Are there alternatives to the competition-downwards that for-profit companies offer? Is there any way to imagine that the private sector would have any incentive to provide a higher quality/more expensive incarceration situation? If we kicked out the private sector completely, the government, like most monopolies, might have little incentive to keep its costs down or do a better job (measured by recidivism rates in the community). Would the charter-school model (publicly-financed but privately-operated school systems) work better for the criminal justice system? Maybe not, since one reason charter schools keep up their quality, is the ability of parents to monitor their performance. Who monitors the quality of life in prison?

One of the most serious problems with the entry of for-profit businesses in the criminal justice system is their drive to expand the need for their services. Companies like Geo Group spend a lot of money urging state legislatures to criminalize more offenses for longer sentences. Most for-profit companies try to expand demand for their product, we’re used to that. But in the incarceration business, this drive to expand means more Americans spending more of their lives incarcerated.

Government industries, like other monopolies, can be inefficient, expensive, and cruel. But the private sector can also act badly, for different reasons. Be careful what you wish for!

Some Useful Materials

A video on externalities from MRU:

Read about pollution from ferryboats

A podcast on requiring police liability insurance in Minneapolis

A short update on private prisons in the United States

Media Attributions

- Antiguo_faro_de_Akranes,_Vesturland,_Islandia,_2014-08-14,_DD_008 © Diego Delso is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- negative externality–antibiotics © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- positive externality, vaccination © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license