14 Tools of Finance: Stocks, Bonds, Mutual Funds, Insurance

Bettina Berch

Consider this

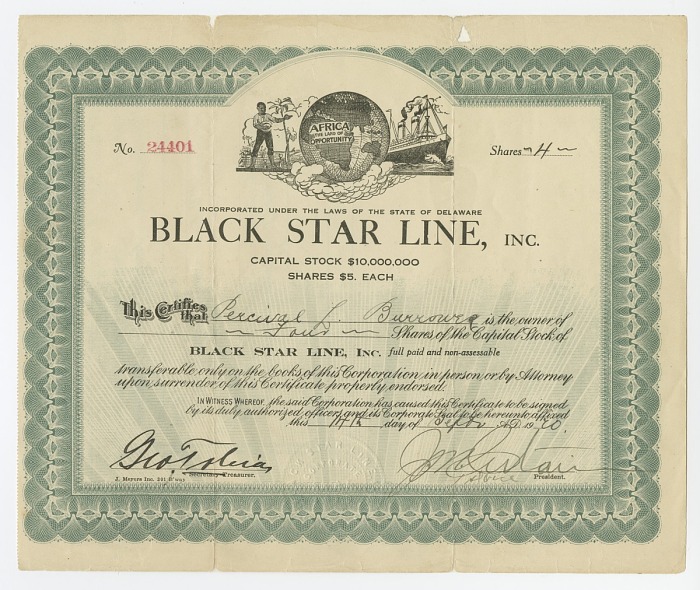

The Black Star Line, founded by Marcus Garvey in 1919, was a Back-to-Africa shipping line. In later years, Garvey’s Pan-Africanism inspired various radical movements, like the Nation of Islam and Rastafarianism. Seeing this stock certificate, might make you wonder–isn’t it kind of capitalist to raise money by selling stock? How do you think Garvey’s very revolutionary supporters would have viewed buying such a stock certificate in 1919?

Looking at economic growth, we saw that the production function determined how much we could produce, given our inputs. Increasing various inputs (K, H, L, N) is key. Many individual businesses try to grow by expanding their K, or physical capital. Often that means raising fresh funds to buy new equipment or rent larger factories. They raise this money using various financial instruments, in what’s called capital markets, which we can now explore.

Bonds

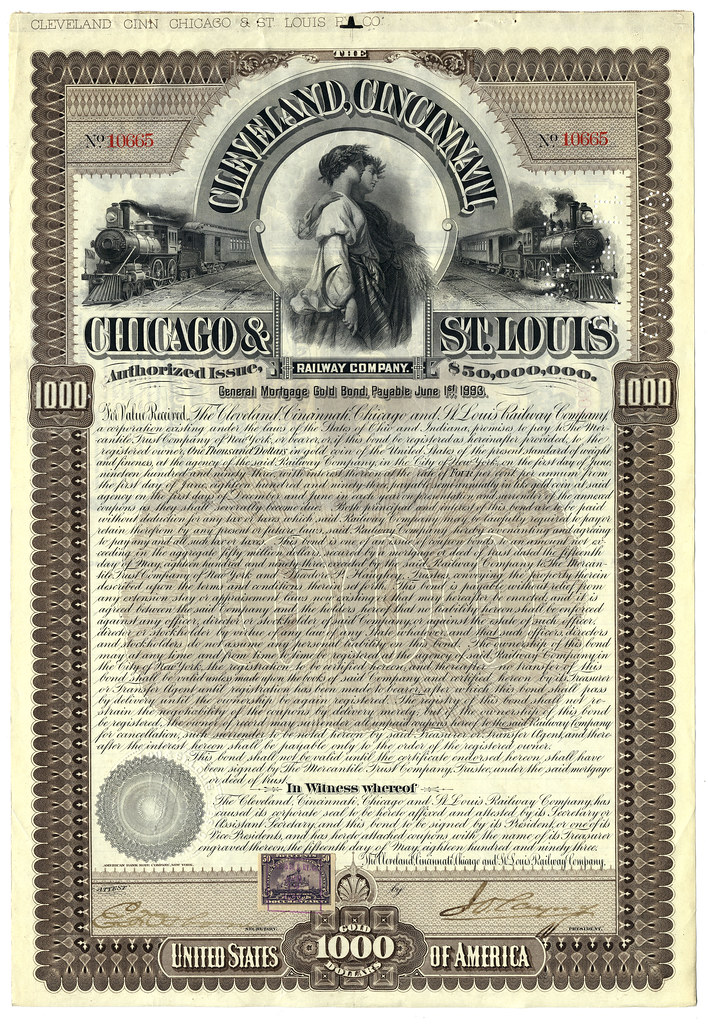

Sometimes a business–or a government–will raise extra funds by issuing bonds. A bond is like an IOU, a promise to pay back money that’s been borrowed. Formally, a bond should have a maturity date, a stated value at maturity, and the name of the issuer. The building of railroads in America, in the late nineteenth century, was largely financed by the issuance of bonds:

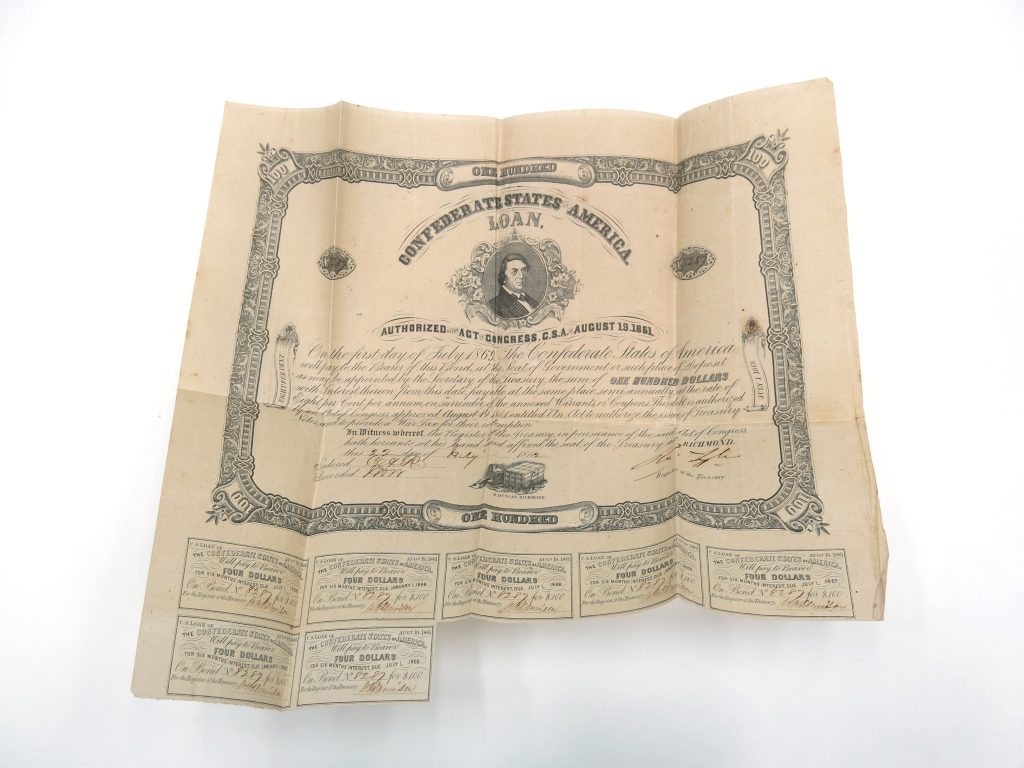

Governments also raise funds to build infrastructure or finance wars by issuing bonds. Here is a bond (with tear-off coupons for interest payments) issued by the Confederate States to finance their side in the Civil War:

War bonds not only raise funds, they raise awareness and support for the war effort among the general population. This photo, of an Asian-American soldier buying war bonds from his officers in 1943, emphasizes that buying bonds is a way to prove loyalty (as if fighting for the team wasn’t enough):

Bonds differ according to the length of time they’re issued for, the riskiness of default, and their tax treatment. Let’s consider each. A bond, like an IOU, has a maturity date, the date when the buyer can ask for their loan back. If the date is relatively soon, like 3 months, it’s a lot more likely to be repaid than a date in 30 years. The shorter the time horizon, the less risky the bond. When a bond (or any other financial instrument) is less risky, it has a lower rate of return than a bond that’s more risky. Which means, other things being equal, a short-term bond will pay less interest than a long-term bond.

But other things are not always equal. If your best friend wants to open a restaurant in the neighborhood and sells bonds to raise funds to get started, that’s a very different proposition than Apple issuing bonds to expand its operations. Neighborhood restaurants have some of the highest failure rates in the country, while Apple is pretty safe. Your friend will need to offer a relatively high rate of return on their bonds compared to what Apple’s offering, because it’s likely they won’t be in business when the bond is mature.

Bonds issued by local, state or federal governments usually get favorable tax treatment, which allows them to offer a lower rate of return. How does that work? If I buy a bond from Starbuck’s paying 10% return or I buy a New York City bond offering 5% tax-return, I have to weigh how much I will get in the end. After I pay income tax on Starbuck’s 10% interest, I may have less money than I would have had with the tax-free NYC bond.

So, bonds differ in their riskiness (according to the length of loan and the stability of the issuer) and their tax treatment.

Stocks

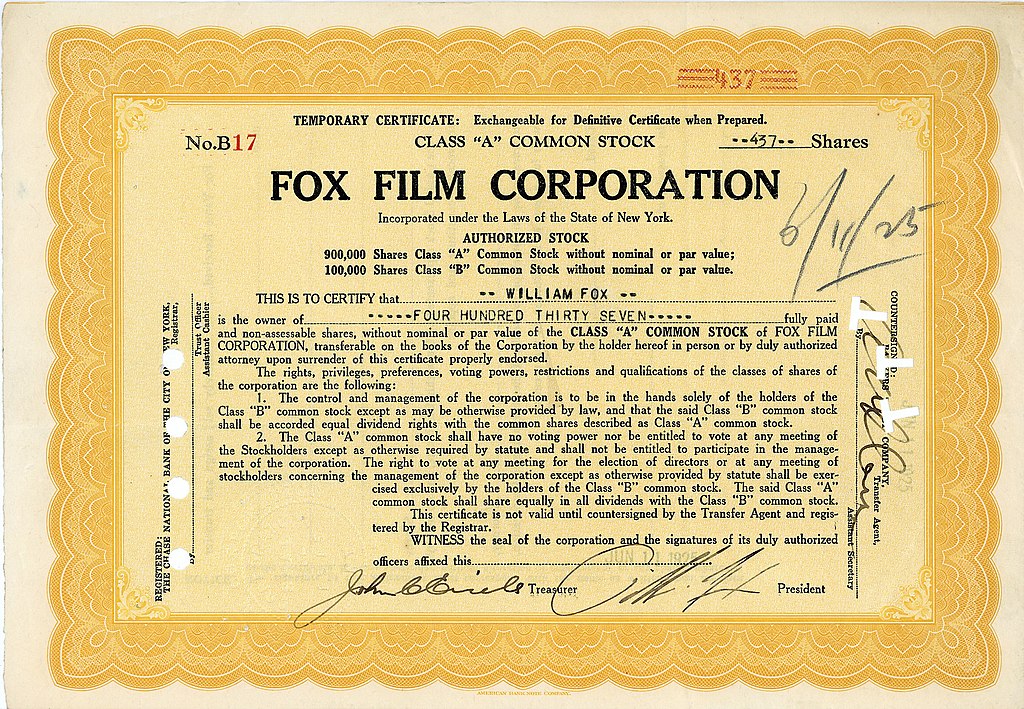

Business can also raise funds by issuing stock in the company. A share of stock represents part ownership in the company. This can mean the right to attend annual meetings of the company, a vote in some elections or referenda, and a share in the company’s gains or losses. The bond was just a loan of money; stock is actual ownership in the firm. You’re not just loaning your friends money to open a restaurant, you’re telling them how to run the place! This ‘ownership’ aspect, is why this is called equity finance–as a stockholder, you’re getting equity in the company. With stocks, the market price of shares indicates peoples’ expectations of profitability. Let’s look at some stock certificates, starting with this one, issued by Fox Film to the president of the company, William Fox (perhaps another propaganda move):

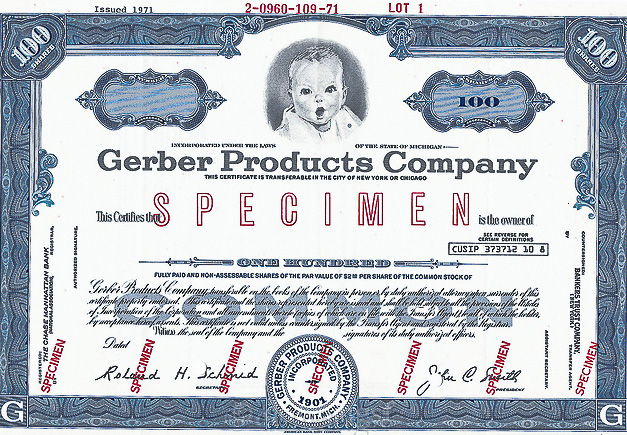

These days, stocks are transferred virtually, but last century, paper stock certificates were sent to buyers, so they often replayed the company’s logo:

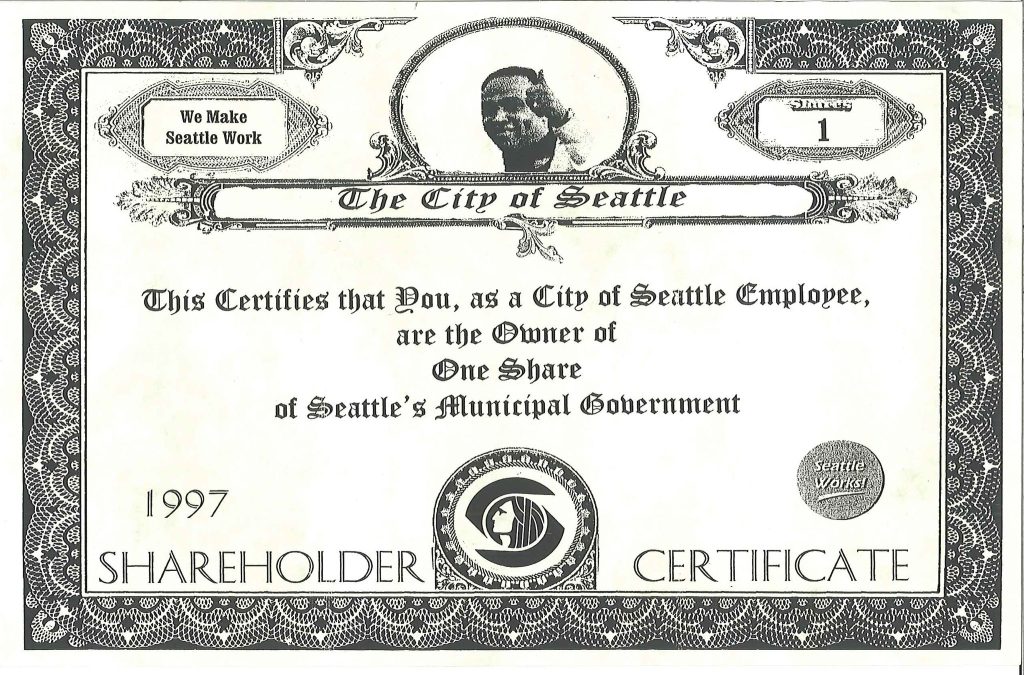

We have come to understand that ‘buying stock’ in something is a metaphor for not just being a part owner, but for being a cheerleader for the company’s success. Do you think this ‘stock certificate’ was for real?

Mutual Funds

Let’s say you have $200 and you want to buy some stocks and/or bonds, but you don’t know anything about businesses and you don’t want to learn about them either. You figure Apple is a solid company, but your $200 will buy a little over 1 share of Apple. Suppose Apple goes down for a year? a decade? Putting all your money in one company is risky and you don’t like risk. Enter the mutual fund! It’s designed so the experts build the portfolio, not you. Each fund’s portfolio is composed of stocks or bonds of many companies, allowing you to diversify even with your small stake.

There are two basic flavors of mutual funds. First, there’s the actively-managed mutual fund. A team of highly-skilled and highly paid stock experts discuss ‘the market’ and buy and sell according to their wisdom. But wisdom isn’t cheap. Your payouts from the mutual fund (your dividends) will reflect the profits or losses of the portfolio minus the cost of running the fund, which includes the salaries of all those MBAs and PhDs they hired.

A second type of fund is the passively-managed fund, or ‘index fund.’ These funds build their portfolio by selecting some stock or bond index and buying a proportionate amount of each company on the index. After that, the high-paid staff goes home–the fund’s holdings are on auto-pilot. While these index funds might miss some fantastic market plays, their operating costs are low, without the geniuses on board.

Both the actively managed and the index funds can specialize in different types of industries, different levels of risk, and even different markets of the world. Which kind of fund does better? It’s an issue debated in business schools, with all kinds of clever examples, but index funds usually win, even according to ‘stock experts.’

Derivatives

Ever since the 2008 financial crash, people have had bad things to say about derivatives. They blame derivatives for the collapse of the housing market , the instability of the banking system, and the failure of some major finance firms. So, what are derivatives, that they could be blamed for so much disaster? A derivative is really anything that’s value is derived from the value of something else. In particular, a “financial derivative” is a contract based on an asset. It often comes from a situation with risk, as a means of coping with that risk.

Let’s consider a situation that has an unacceptable amount of risk for me–the risk of not eating turkey on Thanksgiving. Every November I have the same problem. I don’t want to buy a turkey right away, because maybe my brother will invite me to his house, so I will have wasted money on a turkey I won’t eat. But if I don’t buy a turkey because I’m waiting for an invitation, and he doesn’t invite me, and then I go to the shop and they don’t have turkeys left–I’m in trouble. I’d like to have a way to deal with this risky situation. My butcher has a great idea: a Turkey Derivative:

For $5, I get the right to buy a 20-lb turkey for $2/pound, even the day before Thanksgiving! The value of this derivative is derived from the costliness of the stress I’d feel, not getting any turkey at all. Of course, the derivatives blamed for the 2008 Crash were not imaginary turkey certificates, they were ‘mortgage-backed securities.’

Mortgage-Backed Securities

Going into the 21st century, a lot of people thought the surest way to make money was to buy a house, because a house was ‘always’ worth more when you sold it. Hadn’t the house prices just gone up and up, year after year? People were saying that to buy a house was as good as printing money! The housing market was crowded with these speculative buyers, rather than the traditional buyer who saved up for years and applied for small, safe mortgage loans. The banks wrote more and more mortgages, even to borrowers with poor credit history. They then bundled these mortgages and created a whole new item out of them, a ‘mortgage-backed security.’ This is the derivative, since the value of this thing is derived from the value of the mortgages it includes. How was that determined? More or less in the usual way, which means so-called ‘ratings agencies’ like Standard and Poor rate them, gave them a grade. Buyers purchase the mortgage-backed security, the derivative, based on that grade. These derivatives became hard to grade accurately, with bits and pieces of so many different quality mortgages all in one. A bad batch might be worthless. Unraveling defaulted mortgages became even more challenging. The role of derivatives in the 2008 Crash is more complex than this, but you get some idea.

It’s useful to remember that a derivative represents value derived from something else, so it’s only as good as the thing it’s based on.

Insurance

The concept of risk has been floating around this chapter–we’ve seen that the return on bonds varies according to the issuer’s riskiness, the risks of stock or bond ownership can be mitigated by the diversification that mutual funds offer, and finally, we saw that derivatives were financial instruments covering risky situations. There’s one more instrument we need to discuss: insurance. Insurance can cover your home, your car, your health, or your business, against a variety of threats–accidents, weather, floods, death–you name it! Insurance does not prevent bad things from happening–the hurricane will still hit, even if you have hurricane insurance. Purchasing the insurance means that the costs of your catastrophe will be spread out over a larger group of people (the others who have bought insurance). Everyone who buys hurricane insurance pays premiums (an annual charge) for their coverage. If a hurricane hits the homes of 10% of the policy-holders, it’s the premiums paid in by them and the other 90% that will pay for rebuilding the homes of the 10% (minus administrative costs, profits for the insurance companies, etc). But you get the idea– the payouts have a direct relation to the premiums paid in. This might sound obvious, but it’s really important, because it affects the affordability, the cost of those premiums.

Adverse selection

Let’s stay with the hurricane insurance, and think about who buys it. If you live in Chicago or New York City, you probably wouldn’t decide to buy hurricane insurance. Hurricanes are a once in a lifetime experience for these folks. But if you live in Puerto Rico, bad hurricanes can be common, so you’d want to buy the insurance. This might mean that hurricanes will be hitting 90% of the policy-holders. The premiums charged for that insurance are going to have to be high to cover all those payouts. For a long time, before President Obama’s Affordable Care Act (ACA), premiums for health insurance in the United States were very high–because most of the people buying insurance were people who thought they really needed it–like the elderly, or people with chronic illnesses. We call this the adverse selection problem–the only people who buy insurance are the people who feel like they’re going to be needing it badly!

A good analogy is the problem of ‘all you can eat’ buffets. Who goes to them? Skinny people who ‘just want a salad’? No, they go to restaurants where they just order a salad. It’s people with big appetites, the proverbial ‘football team,’ that goes to the buffet. Thanks to this adverse selection, the buffet has to charge a high price per person.

Since adverse selection results in a very high price for insurance premiums–or buffets–people have come up with solutions you might not have recognized as adverse selection workarounds. For instance, many states require all cars to be covered by some minimum insurance coverage. You might be a 100% safe driver, no accident ever, but you will still be required to buy insurance. Having people in the insurance pool who will never draw a payout, allows the insurance to cover a lot of catastrophes. ‘Obamacare’ was named the Affordable Care Act because it was going to make the premiums (relatively) affordable by requiring everyone to buy coverage. This so-called ‘individual mandate’ was not popular, but it was an important way to address the adverse selection problem. Healthy and unhealthy people all have to buy health insurance.

Likewise, have you ever wondered why there are just a few months a year when you can sign up for your required health insurance? That’s also about adverse selection! If people were free to sign up any time, they’d wait till they felt signs of a major disease. If they got through the year with no health scares, they could just pay a non-enrollment fine when they filed their annual income tax returns. Once again, the insured population would be a pretty expensive group of people, and the premiums would be very high. Bottom line–if insurance premiums are going to be affordable, the population paying in has to include some low-risk people who won’t be needing payouts.

Moral hazard

Moral hazard happens when people buy insurance and then act recklessly because ‘they’re insured!’ You buy health insurance and then smoke and drink like crazy–because you’re ‘covered!’ That’s a silly example, but moral hazard can present serious problems.

Did you notice a sign by the front door of your bank, declaring your bank a proud “member of FDIC?” (If it’s not a member bank, keep walking!) The bank has paid premiums to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which guarantees the safety of your deposits up to a certain limit, and monitors the safety of the banks activities. Once a bank joins the FDIC, their calculus for getting into risky propositions changes (that’s moral hazard). If their risky move is successful, the bank does great! If the risky move loses…the FDIC covers it!

Another important situation of moral hazard happens after police departments buy insurance covering their operations. Once the whole department has insurance coverage, people wronged by bad cops can sue or settle, but either way, the insurance company makes the payout. This means bad actors go on and on, since their costs are paid by the insurance company. This moral hazard situation could potentially be addressed by requiring officers to carry individual liability insurance, like doctors and lawyers and other people who can be sued for malpractice. Any officers who kept acting badly would face rising insurance premiums, which could force them to find other kinds of work.

See how economics gives you a different angle on problems?

Some Useful Materials

Read about what all-you-can-eat-buffets have in common with a typical insurance problem, adverse selection.

Listen/read transcript of podcast on bad cops and insurance.

Listen/read transcript of podcast on whether index funds do better than actively managed funds.

Media Attributions

- Stock Certificate for the Black Star Line is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Railway Bond, 1893 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Confederate States Bond, 1867 © Confederate States is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- World War II soldier buying War Bonds © Bureau of Public Relations, U.S. Dept. of War Information is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Fox Film stock certificate is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Gerber Stock Certificate is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Employee Stock Certificate is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license