21 The Aggregate Model: Equilibrium and automatic stabilizers

Bettina Berch

Consider this

Do you look at this house and think, perfectly balanced? Or do you worry it’s one stiff breeze away from disaster? In economics, an equilibrium position means there are no forces moving something away from where it is. It’s at rest. Since in real life it’s hard to know if an economy is in equilibrium, our aggregate model gives us a way of seeing if our ‘house’ is falling off the cliff–and what to do about it.

Graphing the different aggregate outcomes

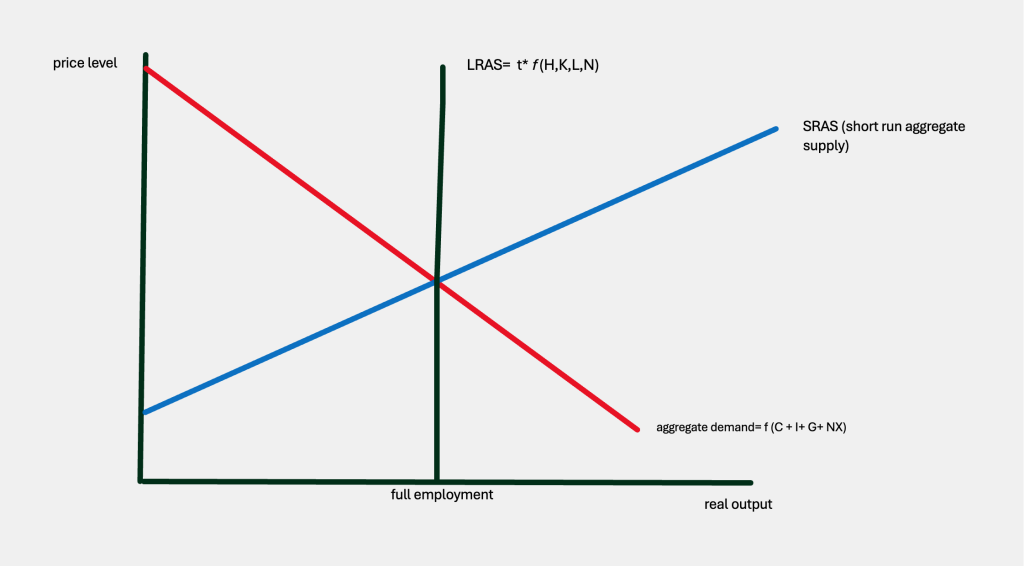

In the last chapter, we developed our aggregate demand curve, our long run aggregate supply curve, and our short run aggregate supply curve. When we put them all together, we might get a graph that looks like this:

In this graph, all three curves intersect at the same point. We would say this economy is in short run and long run equilibrium, since there are no forces pushing us away from the full employment equilibrium that it has reached. And while this is great, this might not happen. Let’s look at two other possibilities:

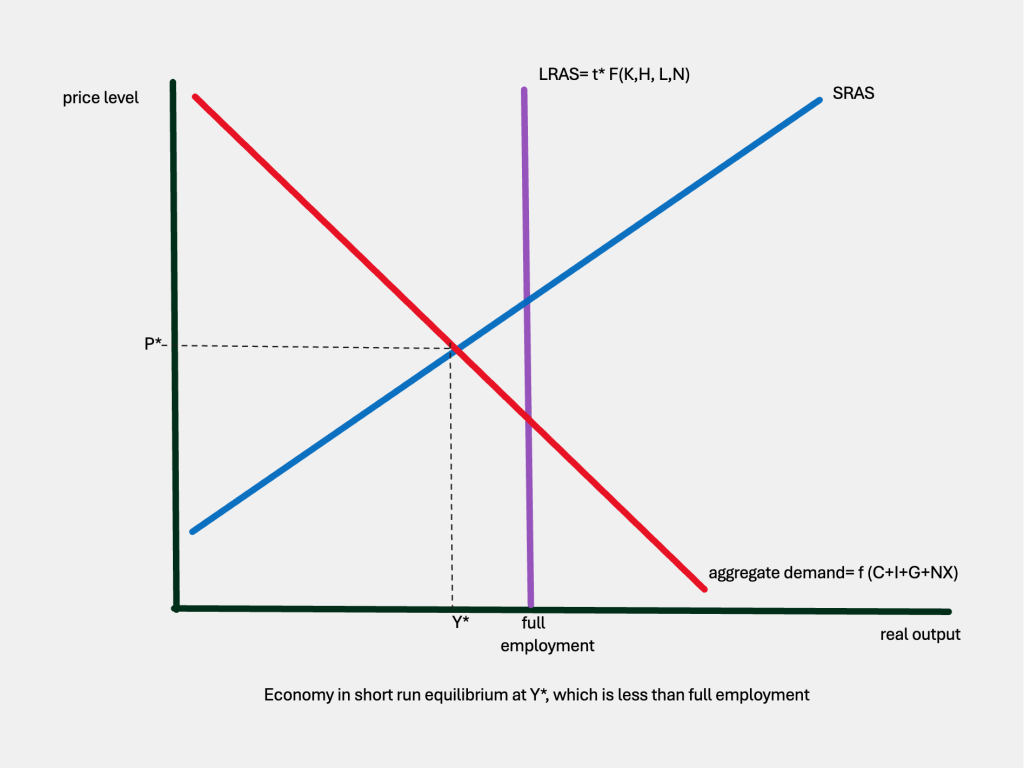

In this graph, our aggregate demand curve intersects the short run supply curve at a point corresponding to Y*, which is less than full employment. This means that in the short-run, which is where we live, our economy is operating at less than full employment. There are people out of work, factories and resources not being used. Our economy is depressed!

We could also have a third outcome:

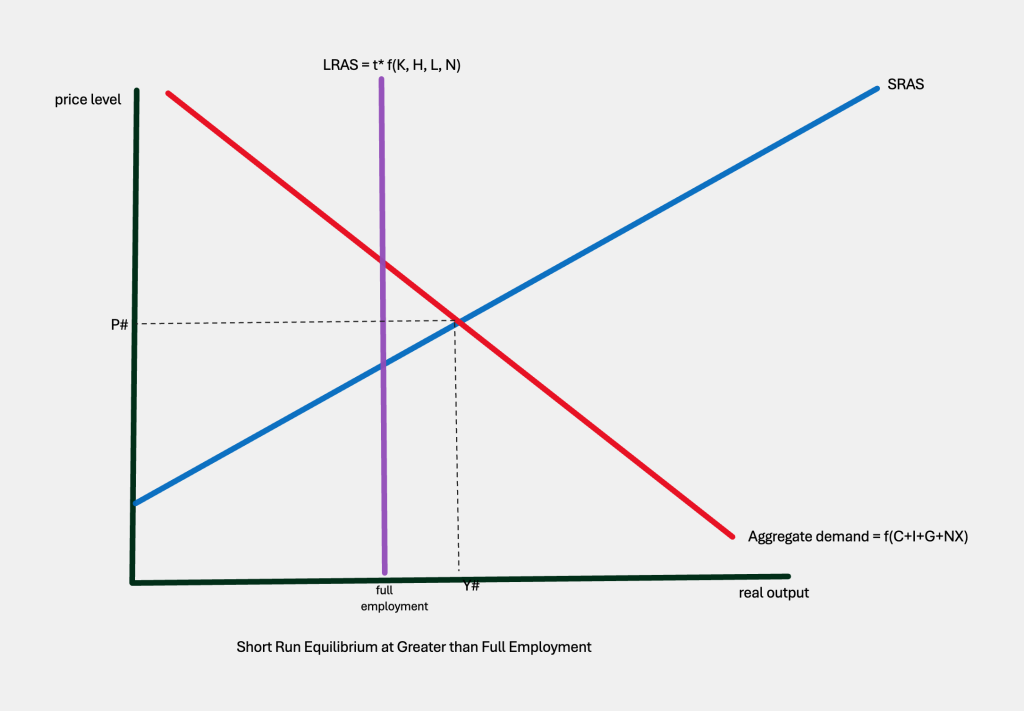

In this graph, our aggregate demand curve intersects the short run supply curve at a point corresponding to Y#, which is to the right of full employment. Our economy is operating at a point greater than full employment. People are working 2 or 3 jobs and factories are running 24/7 with no down-time for maintenance. This may sound great–business booming–but an economy can not run at over-capacity for very long. People and machines will wear out. This economy is over-heated.

While our first graph showed an economy in long and short run equilibrium, the second and third graphs showed an economy whose short run and long run equilibriums did not match up. What happens?

Automatic stabilizers to the rescue: curing the depressed economy

An automatic stabilizer is a built in mechanism that will kick in–on its own–to bring our economy into long and short run equilibrium. These stabilizers may not work very quickly and they may be painful. If policymakers are ignorant, some stabilizers may get canceled before they have a chance to work.

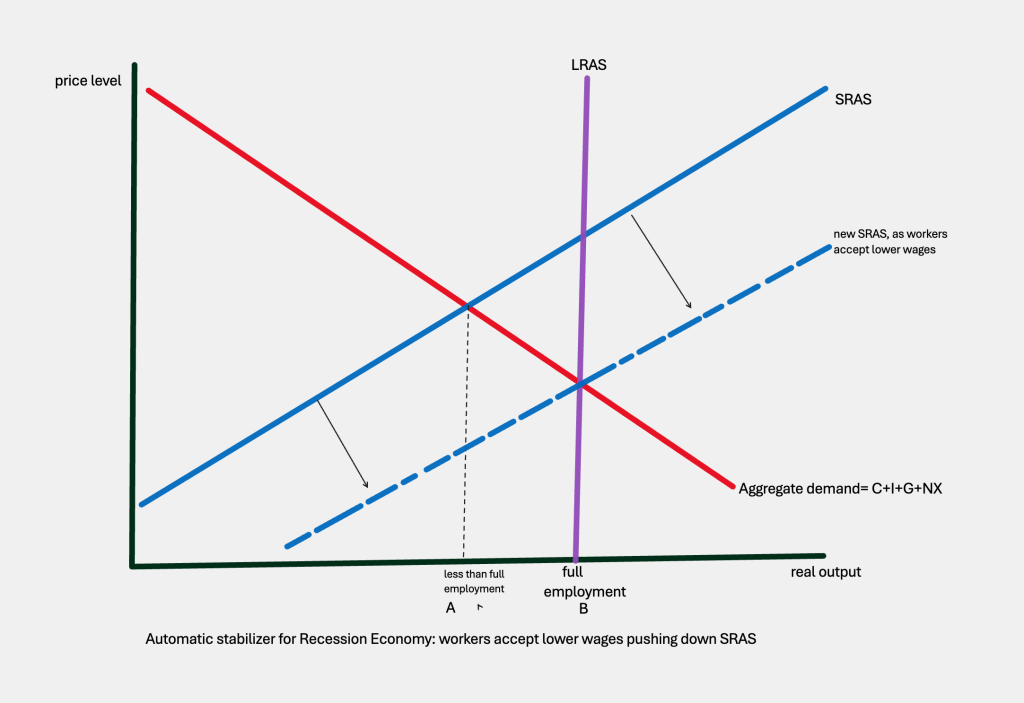

Let’s examine stabilizers for the depressed economy first. The first operates by shifting the SRAS curve. (Sometimes the stabilizer that operates on the SRAS is called a ‘long run self adjustment.’) Imagine we live in a small town with only one factory employing us. A recession grips the economy and our factory closes. We are all thrown out of work. At first we get unemployment benefits, then we borrow from family and friends. Before long, everyone we know is tapped out, broke. Then one day, there’s an ad in the local paper, telling us our old factory has been bought. We’re invited to apply for our old jobs immediately. But–they’re warning us in advance–the new factory will pay us half of what we were paid before.

Some refuse to even consider working for half-pay. Some say they don’t like it, but they could work for a while to pay off debts, get back on their feet. The bottom line? The new factory re-opens, operating with labor costs cut in half. Other things being equal (ceteris paribus), this will shift the short run aggregate supply curve downward, or to the right. We end up in short and long run equilibrium at a lower price level and full employment. This stabilizer, driven by input-cost savings that shift the SRAS downwards, can be cruel, and it can take a very long time to take effect–but it should, eventually, get the job done.

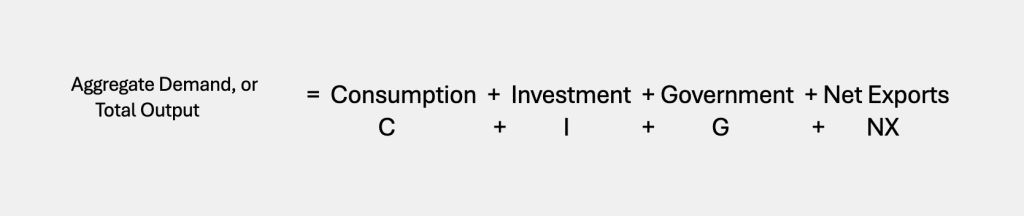

A second stabilizer operates by shifting the aggregate demand curve upwards or to the right. Remember, the position of our aggregate demand curve is determined by its components:

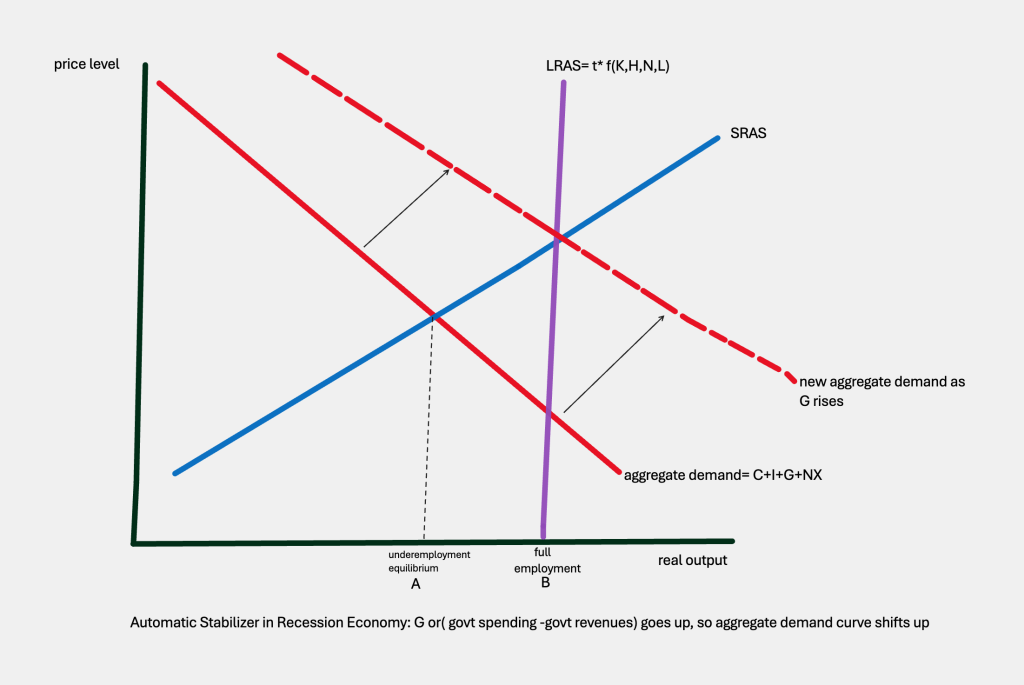

Now we are going to define G (government) as a ‘net’ term: G = [Government spending – government (tax) revenues]. G gets larger when the government is spending more than it’s extracting from the economy. So, what happens to G in an economy that’s depressed, like that town where the factory closed down?

First, think of all those unemployment checks being sent out and the soup kitchens the government had to open. Government spending is going up. At the same time, government tax revenues will be falling, since the unemployed people aren’t paying taxes and the closed down factory won’t be sending in business taxes. If government spending goes up and its revenues are going down, G is increasing. In our aggregate graph, that means our aggregate demand curve will be shifting upward, or to the right, since G is one of its determinants:

We have one automatic stabilizer shifting the short run aggregate supply curve and another stabilizer shifting the aggregate demand curve, moving a depressed economy to full employment equilibrium in the short and long run.

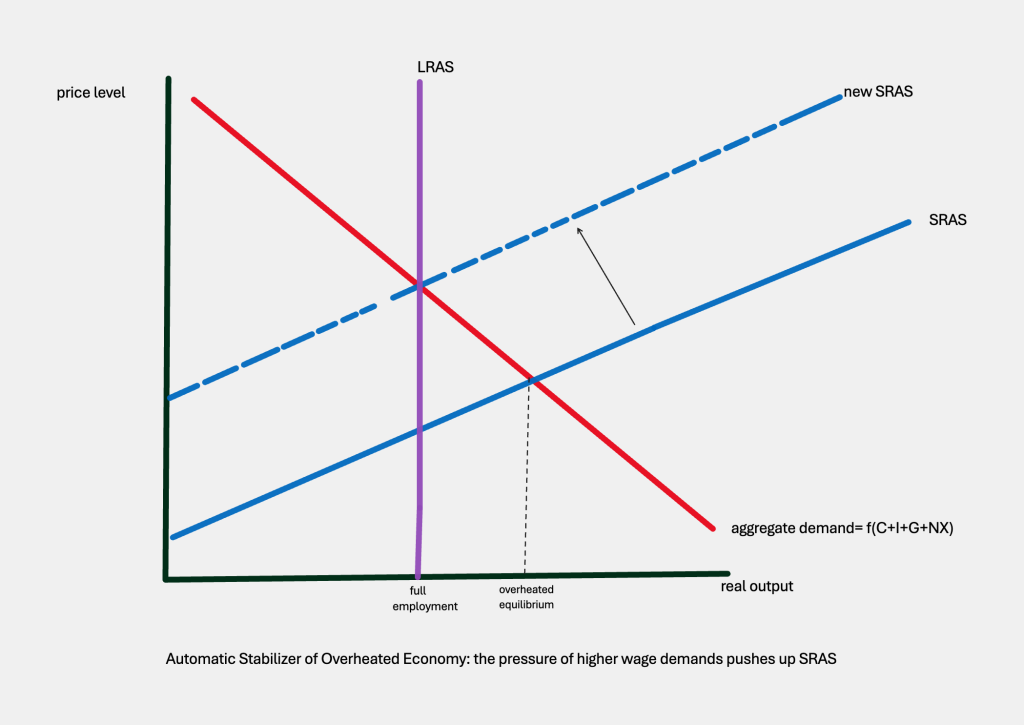

Automatic stabilizers to the rescue: curing the overheated economy

In our overheated economy, the SRAS intersects the aggregate demand at greater than full employment. Let’s consider first the automatic stabilizer that operates through the short run aggregate supply curve. This time everyone in town is already working 2 jobs, and the employer asks us if we’d take another half-shift? For how much, we’d ask? Someone says they’d work for triple wages, and we all agree. Higher wage demands will shift the SRAS upward or to the left. We end up back at full employment equilibrium at a higher price level:

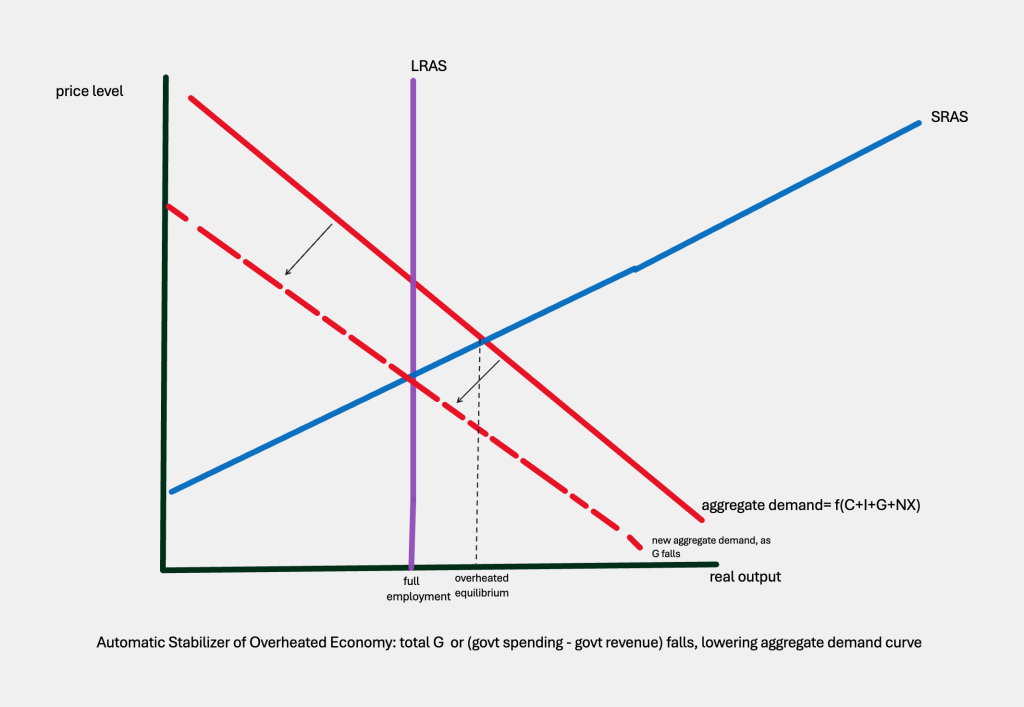

A second automatic stabilizer will operate by changes in G, a component of our aggregate demand curve. Recall from above:

G = government spending – government revenues.

In our overheated economy, government spending goes down, since government isn’t issuing many unemployment checks and the soup kitchens have closed. Government revenues have increased, since we’re each paying taxes on a couple jobs now, and factories are paying big taxes too. When government spending goes down and revenues go up, total G goes down, shifting the aggregate demand curve downward or to the left. We have returned to long and short run equilibrium at full employment.

Are there problems with automatic stabilizers?

With the first stabilizer, the wage cuts shifting the SRAS downward in the depressed economy, we said it might take a long time to be effective. (When the auto plants left Detroit, people didn’t do a quick pivot to different types of work. Many people are not flexible about jobs at all.) Societies can only endure so much mass unemployment before the social fabric falls apart.

Another problem comes from people who would like to get rid of the stabilizer that operates through changes in G. Specifically, they push for legislation requiring the federal government to run a balanced budget. They believe such a law would promote government responsibility, arguing that if ordinary people have to balance their budgets, so should governments. A balanced budget law that said government spending always had to equal government revenues, would mean that for the equation:

G = government spending – government revenues

G would be required to be zero. If G must always be zero, it can’t shift that aggregate demand curve to the right or left and automatically bring us to full employment. A law requiring the federal government to have a balanced budget would remove one of our two automatic stabilizers. Not a good idea!

Luckily, we have more tools in the kitbag. In the next chapter, we will explore monetary and fiscal policies.

Some Useful Materials

Watch a video on how the aggregate model reaches equilibrium.

A simple video featuring unemployment insurance as an automatic stabilizer.

Media Attributions

- House on Edge © Cindy Tang

- Aggregate Equilibrium © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- eq at less than full © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Equilibrium at Greater than Full employment © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- automatic stabilizer –wage cuts © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- components of agg demand © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Automatic stabilizer in a recession: G goes up © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- auto stab–expensive wages © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- auto stab–g goes down © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license