22 The Aggregate Model: Discretionary (Monetary and Fiscal) Policy

Bettina Berch

Consider this

The Works Progress Administration (WPA) was set up in 1935 to help revive the U.S. economy during the Great Depression by giving unemployed people jobs. Artists of all kinds were supported, in addition to people working in construction/infrastructure. This poster and the amateur piano contest it advertises, were WPA projects. In the 2020s, the idea of our government paying to run leftwing theater groups or to archive slave narratives would run into all kinds of culture war objections! While there were objections to the government programs of the Great Depression, they were mostly from people who didn’t believe they would work. Let’s take a look!

In the previous chapter, we identified three potential outcomes from the aggregate model: an economy in recession, an overheated economy, and an economy in long/short-run equilibrium. We know that an economy in short and long run equilibrium needs no fixing. It’s the other two that need help. We also saw that automatic stabilizers could kick in and bring an economy into short/long-run equilibrium, but those stabilizers might require a socially-unacceptable amount of suffering and a very long time. Economics offers two more options: monetary policy and fiscal policy.

Monetary Policy to the Rescue!

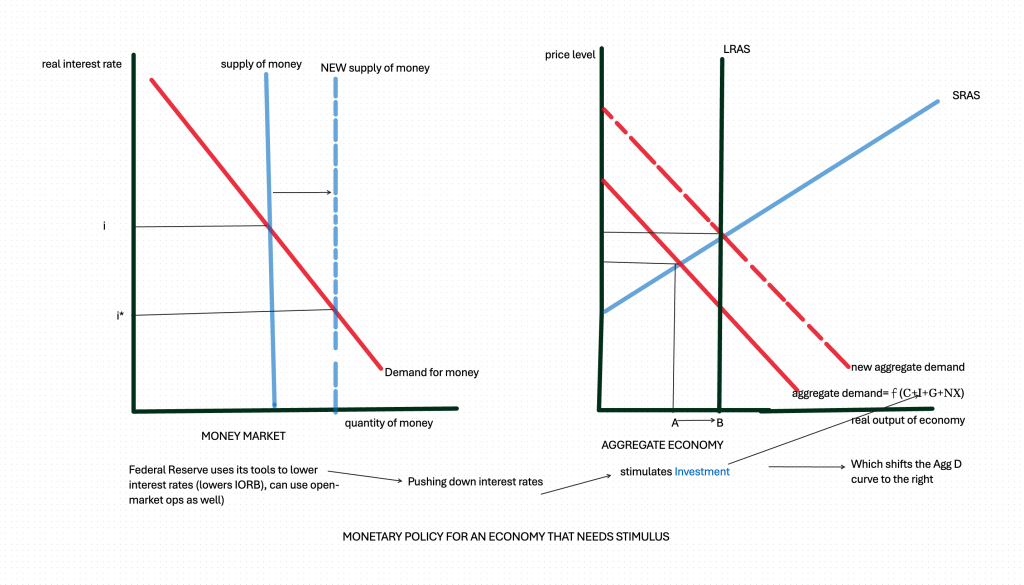

As we saw earlier, one of the jobs of our Federal Reserve is to create monetary policy to steer our economy towards their goals: price level stability (inflation at 2%) and maximum employment (unemployment around 4-5%). Once the Fed has evaluated data on the current economy, they use their tools to move interest rates in a direction that will either push interest rates up or down. Their interest rate changes will either stimulate or dampen Investment activity. Since Investment is a component of Aggregate Demand, changes in Investment will shift the Aggregate Demand curve, producing an new short-run equilibrium–hopefully intersecting at the long-run equilibrium as well. We’ll walk through the steps.

Monetary policy for an economy in recession

If an economy is in short-run equilibrium at less than full employment, the Fed can use a variety of tools to lower interest rates. It could lower the required reserve ratio–an old tool no longer relevant with the ratio set effectively at zero these days. Likewise, it could lower the discount rate that it charged member banks for overnight loans–again, less relevant these days, when banks hold ample reserves. The Fed could hold open market operations and buy bonds, increasing the money supply and pushing down interest rates. Open market operations, in this case called ‘quantitative easing,’ were important after the 2008 economic crash, but not so much now, when banks have ‘abundant’ reserves. Instead, the Fed lowers the interest rates offered on deposits by member banks at the Fed (the IORB) and/or buys ‘repos’ from other financial institutions. The lower interest rate increases Investment, pushing the Aggregate Demand curve upward, or to the right, so our Aggregate Demand curve now intersects the SRAS and the LRAS at full employment. We move from Output A to Output B.

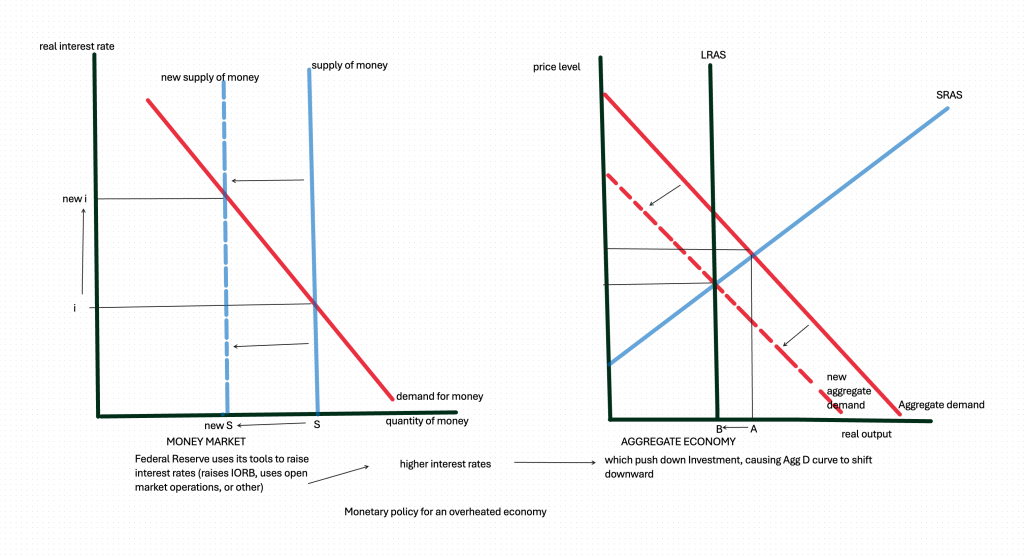

Monetary policy for an overheated economy

If the economy is overheated, running at greater than full employment, the Fed can use its tools in the opposite direction to dampen economic activity. A traditional method–increasing the reserve requirement–is possible, but not likely after many years at zero. They could raise the discount rate they charge member banks for overnight loans. They could run open market operations and sell bonds, decreasing the money supply and pushing up interest rates. Or they could use their newer tools, raising IORB rates for member banks and selling ‘repos’ to other financial institutions. These higher interest rates would discourage private Investment, pushing down the Aggregate Demand curve (since Investment is one of its components):

We would end up decreasing real output from A to B, where we are in long-run equilibrium.

The Fed’s monetary tools have some important strengths. First, the Federal Reserve is better-shielded from politics than any other major institution. Neither the president nor the Congress can fire the Fed Chair or its Board of Governors. A president running for re-election might want to lean on the Fed Chair to ‘juice up’ the economy by lowering interest rates–but the Fed can ignore the pressure. Another great strength of monetary policy is how quickly it can go into effect. The Fed meets regularly every 6 weeks, but more often if it feels the need. If they agree to raise or lower interest rates by some amount at their meeting, it goes into effect very quickly. Indeed, the Fed often makes its intentions known before they meet, so the impact can be absorbed more smoothly.

Fiscal Policy

When Congress passes spending or taxation measures that are signed into law by the President, we call this fiscal policy. In our aggregate demand model, we usually locate fiscal policy in the Government (G) component of the Aggregate Demand curve (C+I+G+NX), although it can also show up in the aggregate supply curves.

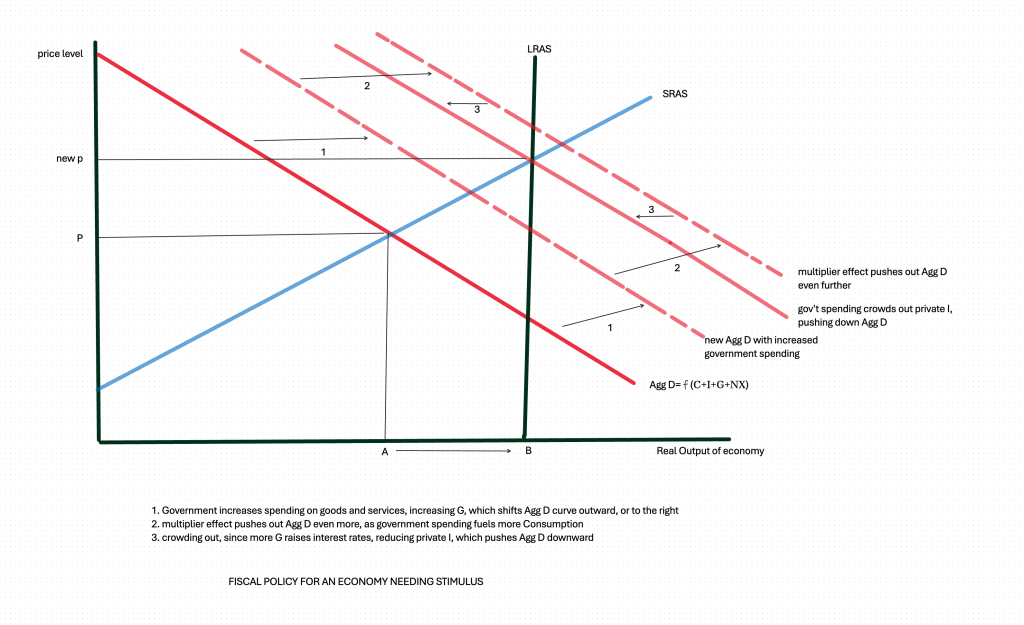

Government spending pushing out the Aggregate Demand curve: the multiplier effect

When the President signs a bill authorizing a $10 billion Infrastructure Bill, to be spent on roads and bridges, let’s say, the first chunk of money might be spent on engineers writing assessments of current infrastructure (arrow #1 in the graph below). These engineers will take their bigger paychecks and spend maybe 40% of the extra on consumer goods and save 60% of the extra–we would say they have a .4 marginal propensity to consume (mpc). Their spending will boost the revenues of a lot of people around them–the florist, movie theaters–wherever those engineers shop. Then those businesses spend more…and so forth. A consumption multiplier will push out our Aggregate Demand curve even further than the first round (arrow #2):

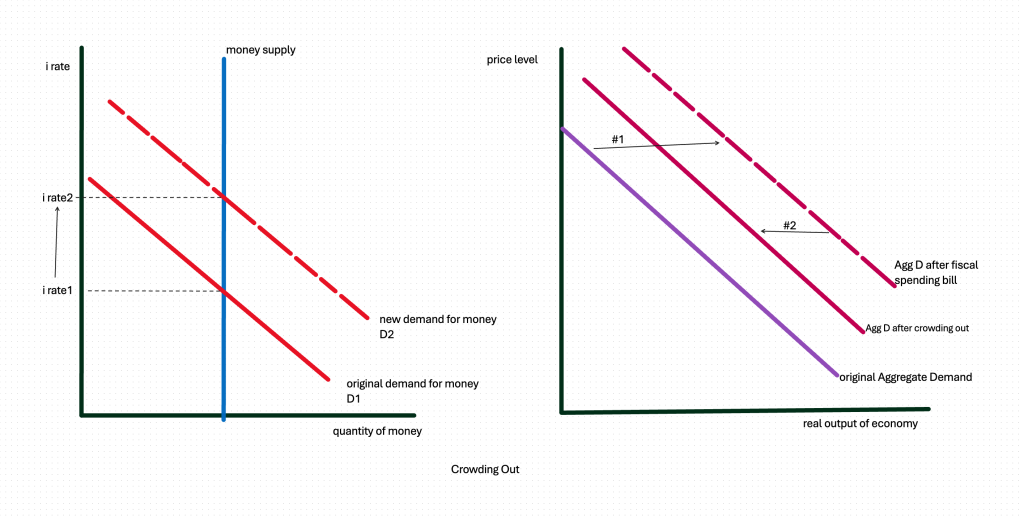

So far we have had a fiscal stimulus, followed by a further push outward from the marginal propensity to consume. But now we will have a force pulling our Aggregate Demand curve downward, or to the left (arrow #3). This is crowding out.

Fiscal policy and crowding out

When the government passed this infrastructure spending bill that encouraged the engineers to go out and spend 40% of their increased paycheck, it increased economic activity overall (arrow #1, in graph on the right, below), which increases the demand for money in the economy. In the money market (the graph on the left, below) this means a shift upward of the Money Demand curve, which will now intersect the money supply curve at a higher interest rate. A higher interest rate will push down private Investment. Since Investment is a component of the Aggregate Demand curve, this will shift our aggregate demand curve back downwards a bit (right graph below, arrow #2).

How much fiscal stimulus is the right amount?

You might wonder, if we’re trying to use fiscal spending to stimulate the economy enough to bring us to full employment, how do we know how big the Infrastructure Bill should be, with a consumption multiplier pushing Aggregate Demand outwards and crowding out pushing us back downwards? Well, we think the marginal propensity to consume might be around 40%, although peoples’ saving and spending decisions may be a product of the economic climate as much as a determinant of curve shifts. Crowding out may also be dependent on the economic climate. If an economy is in a deep recession, it’s unlikely that fiscal spending will be crowding out private Investment, since the private sector has already sidelined themselves. In an overheated economy, a fiscal stimulus would definitely crowd out the private sector–but no one would recommend giving an overheated economy a fiscal stimulus anyway. As with many of our models, the point is to understand the direction of impact, and hope the actual policy-makers act judiciously.

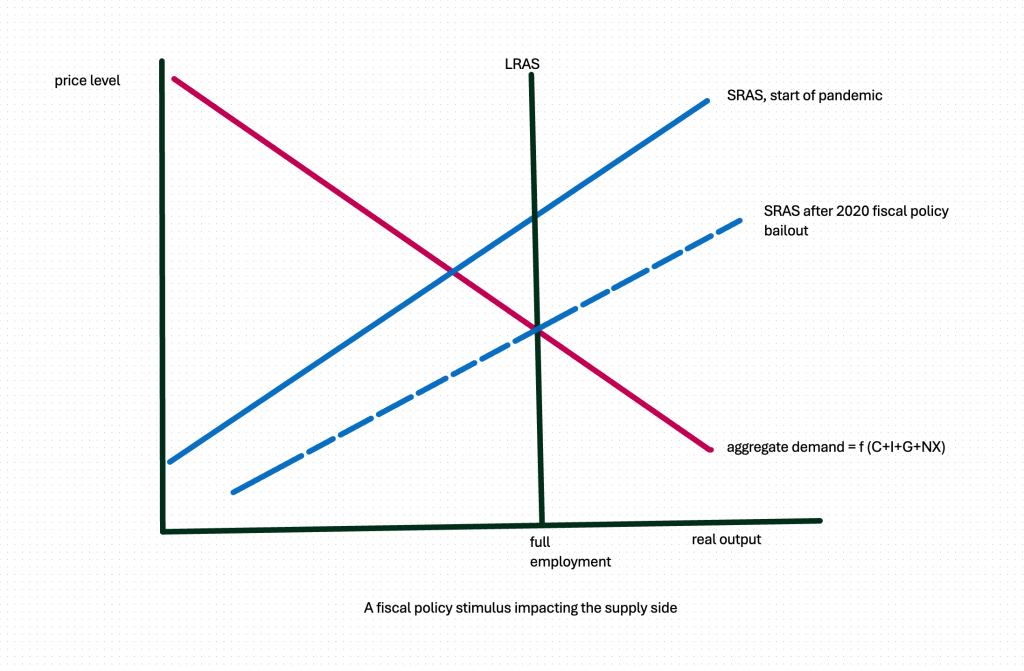

Fiscal policy on the supply side

Fiscal policy usually impacts the Aggregate Demand curve in our models, but it can impact our Aggregate Supply curves. During the Covid pandemic, for example, Congress passed a number of bills to send money to important industries that might have collapsed otherwise–airlines and hospitality industries, for example. These short-term subsidies shift the short-run aggregate supply curve downward, or to the right.

Hospitals and state and local governments also received crucial fiscal assistance. In general, many businesses qualified for assistance through the Paycheck Protection Program, to keep employees on their payrolls, in spite of declining sales. Since these were all temporary, we graph them impacting the short-run aggregate supply curve.

Which is more effective, monetary or fiscal policy?

We found that monetary policy was both quickly implemented and relatively sheltered from the political process. Fiscal policy? It has been a very long time since Congress has been able to pass any legislation at all. The so-called Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 represented a massive achievement by President Biden and his team–but it was exceptional, and not designed as a fiscal stimulus so much as an infrastructure improvements measure. If we really needed a fiscal stimulus bill, because the economy was in a deep recession, and it took Congress 3 or 4 years to pass a final bill–it might not be time for a stimulus anymore! If automatic stabilizers had already taken us to full employment, a fiscal stimulus bill would definitely be coming at the wrong time. Business-friendly fiscal spending, like we had at the start of the pandemic, can pass Congress quickly, but sometimes we need schools and road fixing rather than corporate bailouts.

Moving ahead

While there is more we could say about the U.S. economy, it is time to situate our national economy in the world economy. We need to talk about trade, globalization, development!

Some Useful Materials

Watch a video on automatic stabilizers.

Watch a video on using fiscal policy to reach full employment equilibrium.

Watch a video on using monetary policy to reach full employment equilibrium.

Media Attributions

- WPA poster © Estelle Levine is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Monetary policy impact: recession © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Monetary policy for overheated economy © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Fiscal policy for economy in recession © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- crowding out © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- fiscal stim to supply side © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license