23 The World Economy: International Trade in Theory and Reality

Bettina Berch

Consider this

Sometimes tourist shops like to tape small bills or flags from their customers on their wall, or on a world map. What message are they sending?

Throughout human history, tribes and nations have traded with each other, either to get things they didn’t have, or to get things cheaper than they otherwise could. While trade may be universal, politicians and economists have often disagreed on how it should proceed. Economists are pretty unanimous: the more trade the better, with as few restrictions on trade as possible. Politicians rarely support trade. Some even flirt with autarky–self-sufficiency with as little trade as possible. Usually North Korea is the textbook example of autarky, although that may have ended, as they now export munitions. But even when politicians have to accept world trade, they can’t resist trying to control it, either to favor particular home industries or to chase some national goal. To understand all this, we need to begin with the economists: why do we love free trade?

Comparative advantage

Comparative advantage is an economic principle that says trade relations are mutually advantageous (meaning, good for both sides) when they are based on the relative opportunity costs of producing things. This video goes through the arithmetic clearly; we don’t need to repeat it here. Anyway, it’s a mental computation that most of us make instinctively. If someone moves into your apartment who’s a great chef but terrible at cleaning, and you’re a horrible cook but a fanatic cleaner–we all know the best outcome. Let each of you specialize in what you have the ‘lowest opportunity cost,’ and you’ll have the maximum output. When one side is better at one thing, and the other side better at something else–we call that comparative advantage. Specialization-and-trade seems like a no-brainer when when two countries have complementary strengths. But what if one country is better at everything? Should they still trade with anyone?

Absolute advantage

Even if one country is better at producing everything–even if it has an absolute advantage in the production of all things–it should specialize in producing its lowest opportunity cost thing, and trade to get higher opportunity cost things. Again, the same video goes through the arithmetic with two sample countries very clearly. How about a more intuitive example? Imagine Renee is an artist who can produce one $4000 painting in a 40-hour workweek. To realize those sales, she needs an office person to send invoices, do mailings and pack and ship paintings. Renee hires Jack to do this office work, paying him $500 per week. All is fine until she goes into the office one day, and watches Jack work. ‘He’s so slow,’ she thinks. ‘I could do what he’s doing in half the time!’ Should Renee fire Jack and do the office work herself? Or should she keep Jack, even though he’s slow? (And don’t avoid the question by interviewing different office workers!)

If she fires Jack, she’d have to spend 20 hours a week on office work, leaving her only 20 hours to paint. She’d produce only half a painting a week, so her weekly income would be $2000. If she keeps hiring Jack, her weekly output of one painting would bring her $4000, minus $500 to pay Jack, so she nets $3500 for the week. Even though she is better at painting and better at office work, it still makes sense for her to specialize in the highest value use of her time, and pay Jack to do the other work.

Problems with comparative/absolute advantage trade theory

While arithmetic and intuitive logic both say comparative/absolute advantage are solid arguments for countries to specialize and trade, there are important arguments against it.

First, it’s risky. Economies that are very specialized are left vulnerable to trends they can’t predict or control. An economy specializing in growing coffee beans can be ruined after a few bad crops. Countries that specialized in growing tobacco didn’t expect world tastes to change. Diversification can be safer than specialization.

Second, specialization leaves a country dependent on others, for something that might be very essential. If rice is a key cultural staple food, as in Senegal or Japan, ensuring domestic production–even if it’s cheaper to import rice– is essential to the protection of national identity. Or consider guns and tanks–did you ever wonder why some countries keep producing them, even if they are not very high quality? Many countries can’t run the risk of depending on a trade partner for weapons, only to find themselves at war with their previous partner. Many countries choose self-sufficiency in key areas, even if it is costly.

A variation on this is the ‘infant industries’ argument– the idea that a young country might have a few industries that it protects from competition from imports, until home production ‘gets on its feet.’ Often producers of textiles or even wood matches or beer (low tech products, widely used domestically) ask for import protection so they can establish themselves. Historically, these very industries have been protected in various countries (and it’s difficult to end those protections once the domestic industry is actually competitive).

Comparative advantage may cost real people their actual jobs, their livelihoods. If comparative advantage says that Vietnam should produce shoes and the United States produce computer software, we end up with a lot of unemployed shoe workers in the United States, who can’t turn around and become software coders. There’s an assumption behind the comparative advantage model, that resources will ‘flow’ smoothly into the industry demanding them–but human resources (aka ‘people’) aren’t as flexible as financial instruments, smoothly moving to the highest bidder. Sometimes it’s the workers–auto workers, textile workers–who have been loudest in opposition to free trade, knowing it’s their own jobs on the line. Unlike other situations, in world trade, the winners don’t compensate the losers.

Another way of evaluating the benefits of trade: welfare analysis

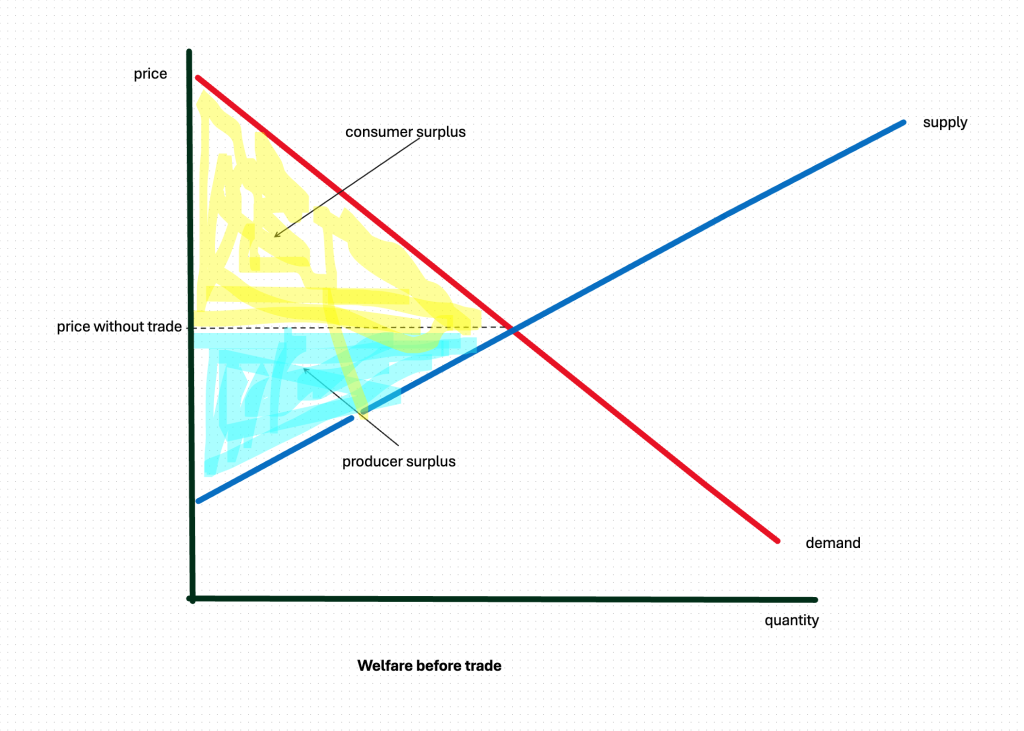

Welfare analysis can be particularly useful in evaluating the gains and losses from a trade policy change. First, let’s remind ourselves of the the types of surplus and locate the equilibrium price in an economy before trade:

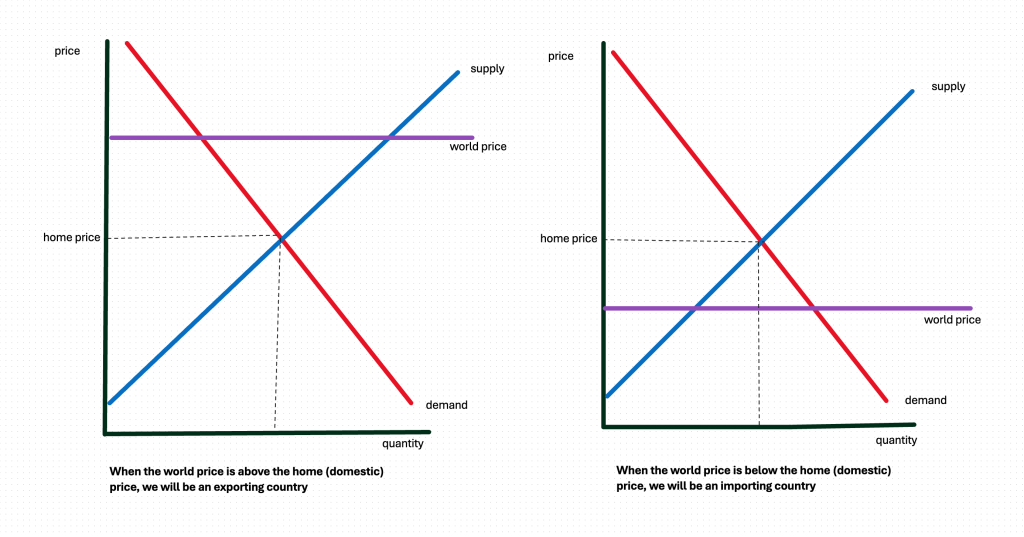

Now let’s open this country up to trade with the rest of the world. If the world price is higher than the home price (also called, the domestic price), domestic producers will raise their selling price to the world price–for everyone. Domestic consumers will either pay that higher world price, or do without. We will be an exporting country of that good.

If the world price is lower than the domestic price, domestic consumers will now be paying that lower world price. We will be an importing country of that good.

Welfare analysis of trade: the exporting country

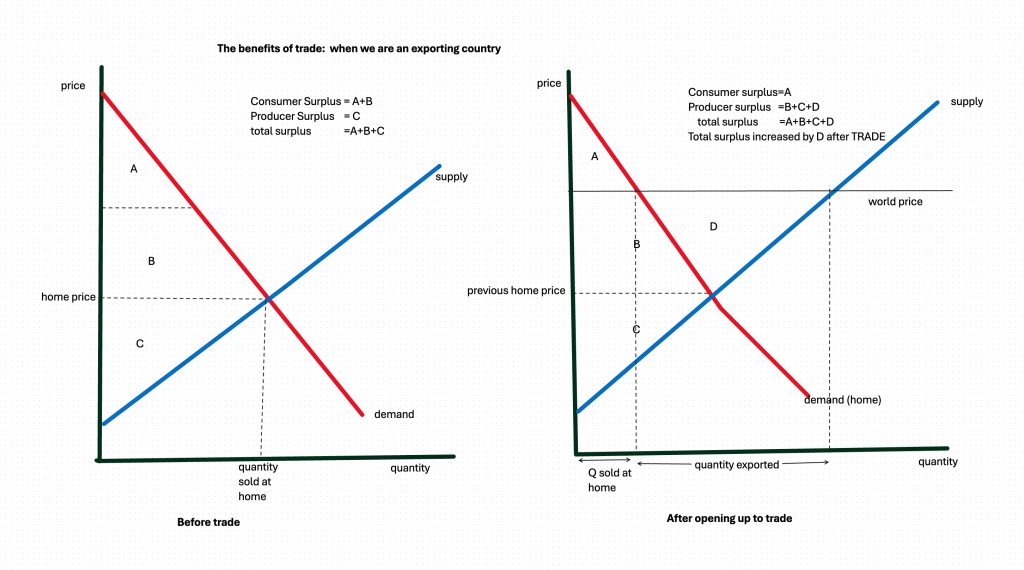

Let’s use welfare analysis to see the gainers and losers when we open up to trade and the world price is higher than our domestic price. We become an exporter of some good, like wheat or beef:

Before trade, CS (consumer surplus, the area below demand curve and above market price) is A+B. And PS (producer surplus, the area above the supply curve but below market price) is C. TS (total surplus) is A+B+C.

After trade, the new CS is just A. The new PS is B+C+D. TS is now A+B+C+D. Thanks to trade, total surplus in our country has increased by D. However, consumers now have less surplus than before, and producers have taken surplus B from consumers and gotten all of the new surplus D. Doesn’t this sound a little more like reality than the comparative advantage model? Yes, there are gains from trade–but there are losers as well.

Welfare analysis of trade: the importing country

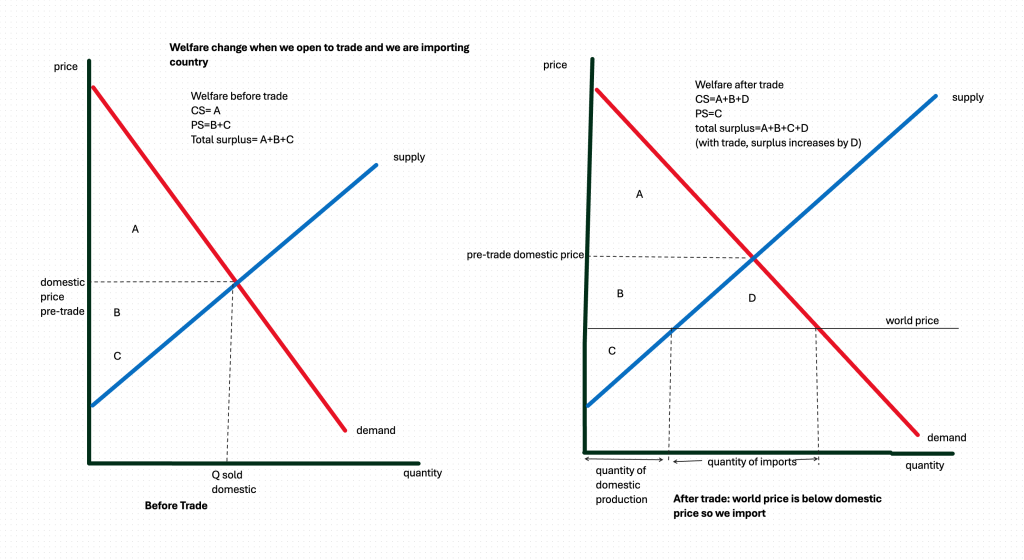

If we open our country to trade and the world price is lower than what domestic producers had been charging, domestic consumers will now be paying that lower world price:

In the graphs above, CS is A before trade, and PS is B+C, so TS is A+B+C. After opening to trade, CS is A+B+D. CS is just C. TS is A+B+C+D. Trade has increased total surplus by D, but this time, it’s only consumers who have benefited from trade. Producer surplus has decreased. These domestic producers are not going to be happy about the competition they’ve gotten from foreign producers!

Domestic producers fight back: tariffs

In the first case, when our country became an exporter, we saw that domestic consumers were worse off–but consumers of various goods are not a unified group. We don’t all get together and protest more expensive shoes or steel. In the second case, when domestic consumers were better off thanks to a lower world price, it was domestic producers who were harmed. And in many cases, producers are unified; they have industry trade groups, lobbying groups, etc. If the beef industry or the wheat farmers saw their businesses gutted by foreign competition, they’d go to Congress and push for tariff protection.

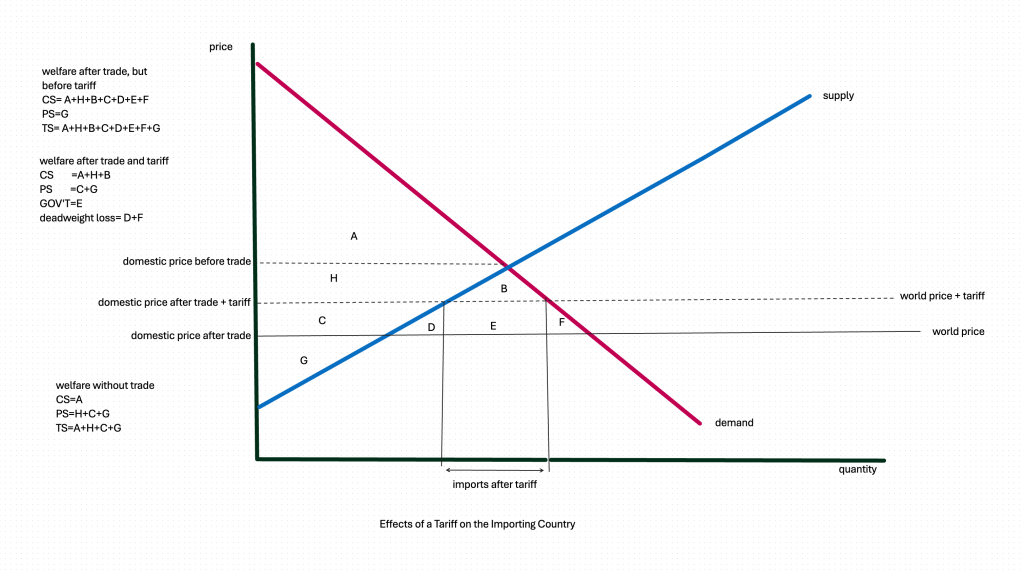

A tariff is a tax on imports–sometimes on a good, sometimes on a good from a particular country. A tariff on imported washing machines will raise the world price of washing machines (which will raise the price of all washing machines):

First, notice that the world price horizontal line has now been pushed up by the tax rate on the imported good. At the new, higher world price, domestic consumers are buying slightly more domestically produced goods, at a higher price than before the tariff. After trade but before the tariff, CS= A+H+B+C+D+E+F. And PS is only G. So TS is A+H+B+C+D+E+F+G.

A tariff on imports is a tax, so we will have government revenues in TS and we have deadweight loss, surplus that does not happen because a tax reduces economic activity. So after the tariff, CS is A+H+B. And PS is C+G. Government revenues are E. The deadweight loss–the loss to society from imposing this tariff– is D+F.

Who gains and loses from tariffs?

It’s usually domestic producers who argue for tariff protection, and as we see in the diagram above, did producers gain area C.

Producers usually argue that a tariff will protect workers in their industry, not the business owners, although computations show that the cost of saving a single job can be a million dollars a job, not an insignificant sum!

Domestic consumers lost C+D+E+F, although it could be argues that, as citizens, they still benefit from area E, as government revenues are spent on the public’s well-being. In real life, consumers face higher prices on the tariffed product.

From a productivity point of view, tariffs–or quotas or any measure that protects an industry from more efficient competitors–lead to inefficiency.

It should be clearer, now, why economists are in favor of trade and against protectionist barriers to free trade. Trade allows countries to specialize in goods and services where they have a comparative advantage. Specialization and trade allow for a higher standard of living. Barriers to trade, like import exclusions, import quotas and tariffs, all reduce social surplus and protect inefficient producers.

Much of this discussion has been a bit theoretical, however. It’s time we looked at some real life trade issues, like the problems of globalization and global supply chains, or the impact of exchange rates.

Next chapter, we return to planet earth!

Some Useful Information

This video uses opportunity cost calculations to show the basis for comparative advantage.

Watch a video explaining comparative advantage and the gains from trade.

Read about Trump’s anti-trade/pro-protectionist point of view.

An evaluation of the impact of tariffs, past and present, stressing the political impacts.

Perhaps the old model of countries producing things and trading with other countries is obsolete. A single product, like an iPhone, is a product of an international ecosystem, based on movement of expertise and parts around the world.

Media Attributions

- A World of Trade © Christine Roy

- welfare before trade © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Trade basics © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Welfare, exporting country © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Welfare changes, importing country © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- tariff © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license