25 The World Economy: The Challenges of Development

Bettina Berch

Consider this

These women are part of a savings circle in Liberia, where they meet on a nine-month cycle to distribute the earnings from their projects. Why didn’t they just go to a bank? Why are they all women?

In the last two chapters we talked a lot about trade, ending with ‘export-led growth,’ an important route to development favored by the so-called Asian tiger economies. Now we are going to focus on economic development–why some countries are wealthy, and others can’t seem to escape dire poverty. What factors seem to make a difference? What could change this?

What is considered poverty?

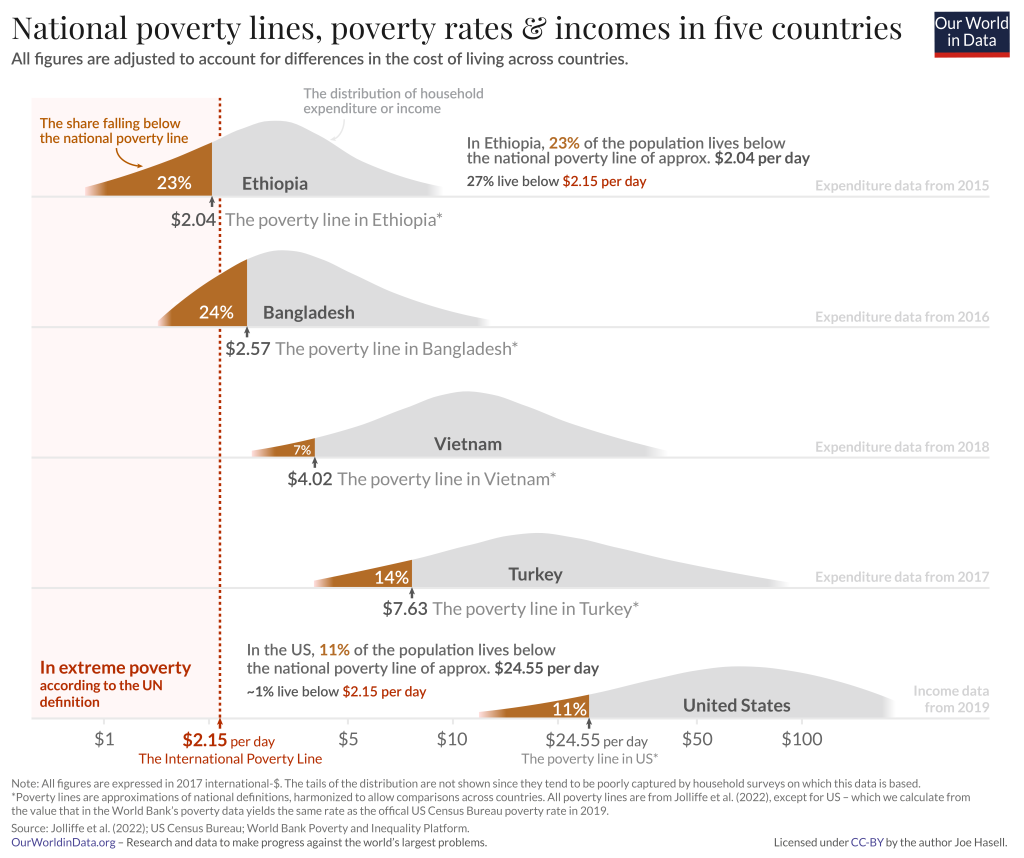

Anyone who has ever visited a place that’s a lot richer or poorer than where they were brought up, knows that these things are relative. Yes, people in Manhattan throw away perfectly fine furniture and appliances that people in Honduras or Vietnam would collect, repair and resell in a hot minute. So while different countries’ standards of living differ, in any given country an economist could study what people consumed and develop a ‘poverty line’–some amount in that country that it’s a real struggle to live on. Consider this chart:

Using an international poverty line of $2.15 a day, you can see that 23% of Ethiopia’s population falls below that mark, while barely 1% of Americans fall below that poverty line. In the U.S., our poverty line is variously determined to be around $24.55 per day, and 11% of us fall below that. Almost everyone in Ethiopia falls below the American poverty line of $24.55.

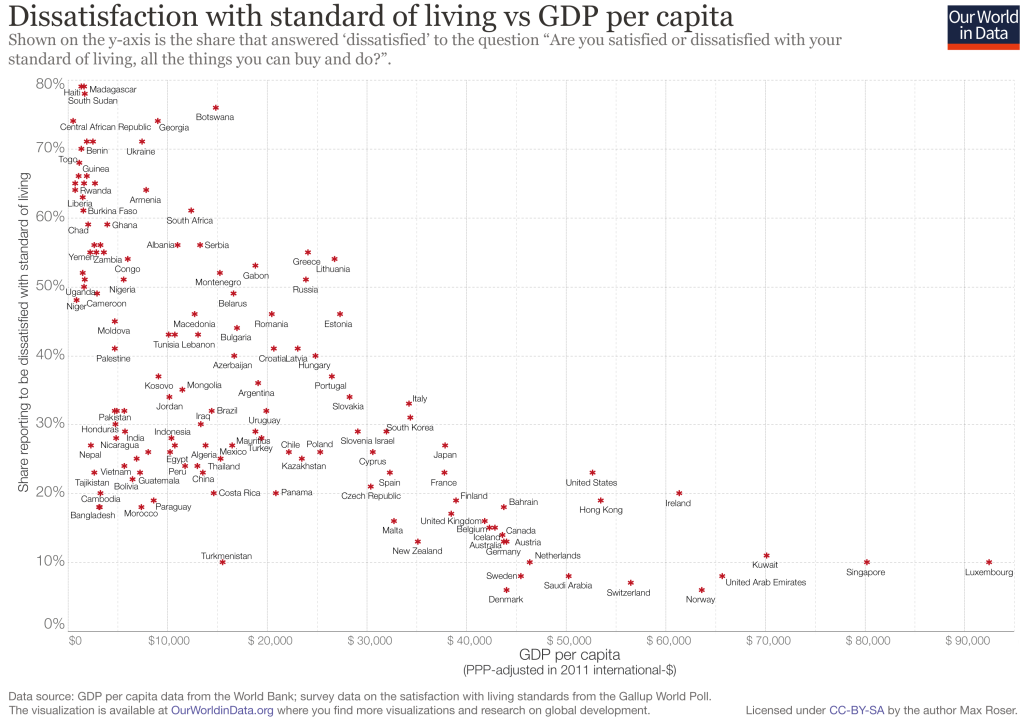

There are people who argue that the people they saw when they visited Ethiopia or Vietnam looked very happy. Wasn’t their ‘simpler’ lifestyle more satisfying? Luckily, researchers have followed up on this with a Gallup poll asking people if they were satisfied with their standard of living or not. Then they graphed % dissatisfied against GDP per capita in the various countries:

Roughly speaking, the lower a country’s GDP per capita, the higher their dissatisfaction with their standard of living. So the question’s somewhat settled: poor people aren’t OK with being poor. Let’s try to figure out why some countries have escaped poverty (since poverty is where we all started) and others haven’t.

What wealthy countries have, that poorer countries lack

Favorable geography can encourage economic growth. Countries with many deepwater ports are better off, since they can import and export easily. A temperate climate and good quality soil can make agriculture more productive. Rivers criss-crossing the country allows the cheaper transportation of goods. On the other hand, deserts or mountain ranges can separate markets, making commerce difficult. Landlocked countries are forced to rely on the ports of neighbors. Hot and humid climates foster many diseases that Western medicine has not addressed. Periodic rainy and dry seasons disrupt peoples’ ability to work.

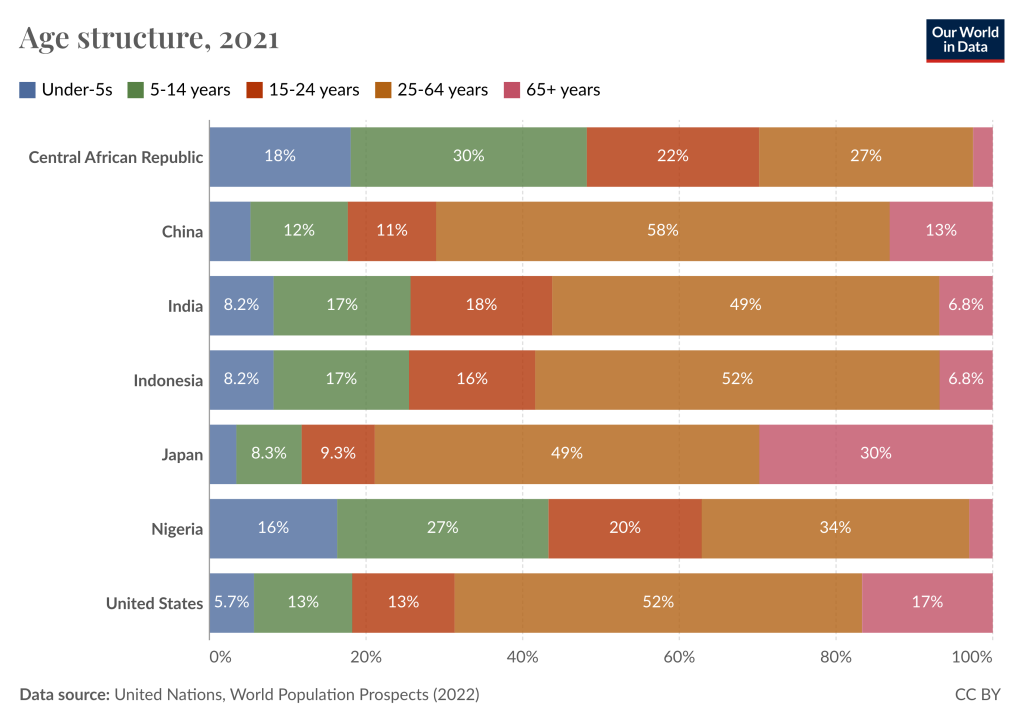

Then there’s demographics. Developing countries often have a higher proportion of children to adults in the population, meaning more people needing to be provided with food and clothing compared to the numbers working to support them. In the chart below, we see that 43% of the population of Nigeria is under 14, compared to 18.7% in the United States. It’s not just the young who need to be supported by working-age people–it’s also the elderly. In Japan, 30% of the population is over 65!

Poorer countries also have fewer resources to spend on maternal mortality, infant mortality, and nutrition. A whole host of diseases, from infections spread by parasites to diseases from human-animal contact, can spread rapidly, with no quality treatment options, in poorer countries.

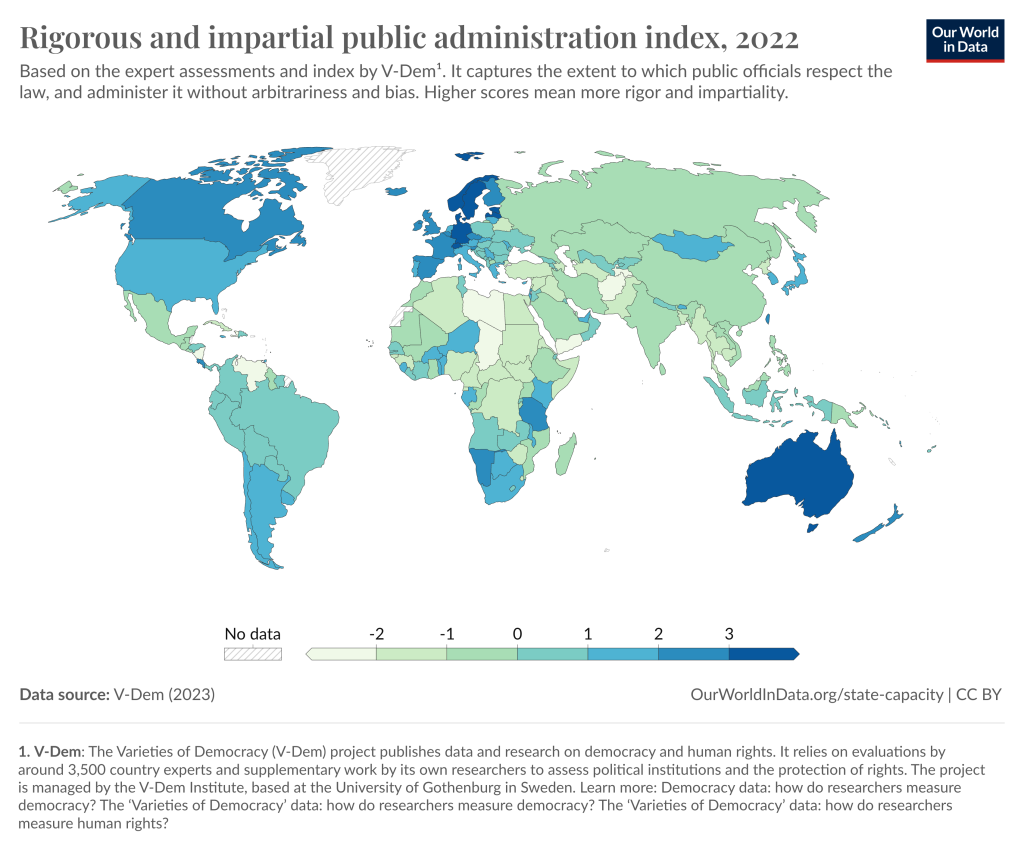

The wealthier countries also tend to have strong political and economic institutions. Traditions like the respect for the rule of law and private property rights make it possible for people with entrepreneurial ambitions to succeed, without the fear that whatever they build will be confiscated. In modern times, respect for the rule of law varies greatly around the world:

For the most part, the darker blue countries in the chart (Australia, Sweden, Canada) have higher respect for the law and are also some of the wealthiest nations in the world. Some countries with the lowest regard for law (Chad, Libya, Afghanistan, Yemen) are also some of the poorest.

In some cases, the foundations of these strong political and economic institutions date back to the country’s colonial history. The American colonies were founded (largely) by Europeans who intended to build lives in this New World. These colonialists built banks, meeting halls, ports, schools. By contrast, many regions of Africa were colonized by Europeans with no intentions of staying any longer than it took to extract valuable resources. They built little infrastructure–few schools, banking systems, legislatures. When the colonial powers were thrown out, there was little left for the indigenous population to build on. Some of these areas remain largely impoverished, to this day.

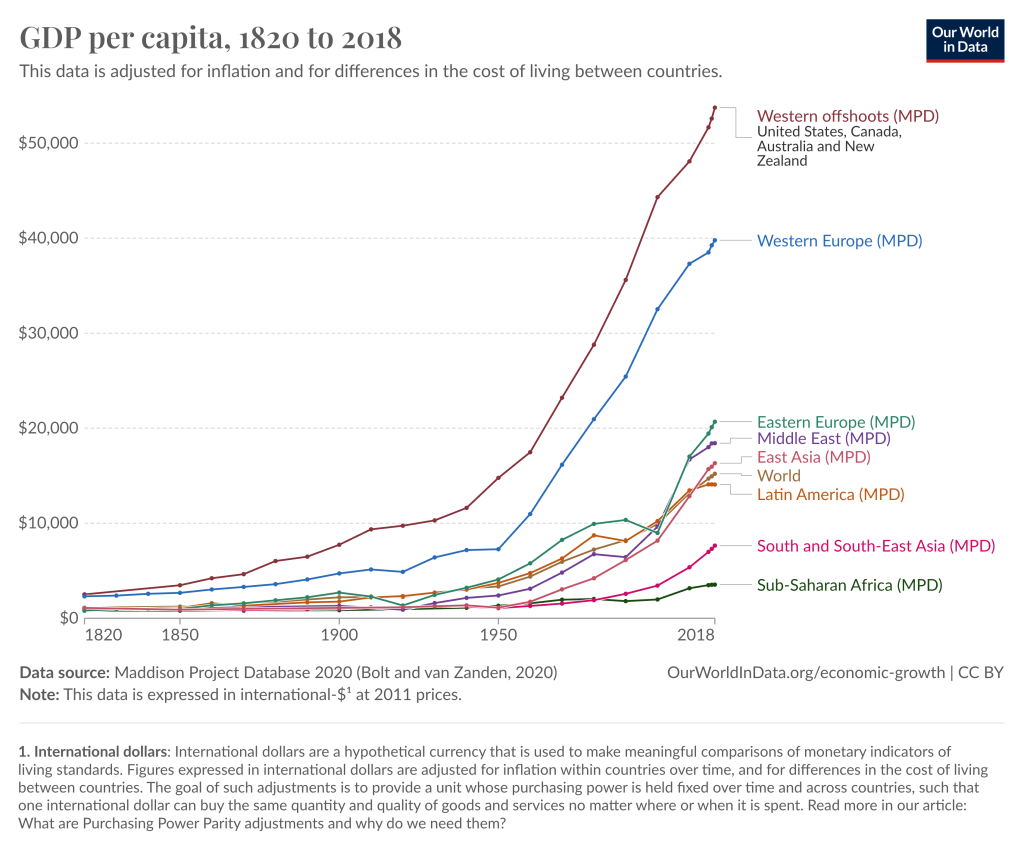

If we compare GDP per capita of people around the world over the last two centuries we see the cumulative results of these and other factors:

Yes, the trend is mostly upward for all countries, but that’s where the similarities end. While most of the world starts out fairly poor in 1820, Western Europe, the U.S., Canada, Australia, and New Zealand show geometric growth rates after 1950.

What can be done about Dire poverty?

First, some things don’t matter as much as you think they do, like a country having great natural resources or not. Many countries in this world have had spectacular growth rates without having natural resources–Japan, Israel. Others have had huge natural resources–Nigeria, Russia–but very low growth rates. Most of the oil-rich OPEC countries offer a low standard of living to ordinary citizens. Guyana’s recent discovery of huge oil reserves has attracted the interest of major multinationals, but Guyana is going to have to be pro-active or its own people won’t reap much benefit. (There’s even a name for this, the ‘resource curse.’)

For a long time, a popular solution for underdevelopment was foreign aid, in various forms, from rich countries. Whether that aid has much brought long-term growth is a hard question to answer without considering alternative uses of those aid funds.

Microcredit

In 1976 an economics professor, Muhammad Yunus, was walking in a village near his university in Bangladesh, when he was stopped by some village women who were asking for money. They could use this money to buy the bamboo they needed to make furniture they could sell. Banks didn’t want to loan to poor people, but if they could have a small amount to buy their raw materials, they could get their furniture business going. Yunus loaned these 42 women the $27 they needed…and microcredit was born. The loan to the women helped them start their business and turn a profit. Yunus decided to go bigger and start a bank that would lend to the poor, and his Grameen Bank was officially opened in 1983. In 2006, Yunus was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, among other accolades.

Yunus was clear that microcredit involved loans that would actually be repaid. In his mind, charity created dependency. Microcredit encouraged financial competence and independence. Loans to small groups, especially small groups of women, could be more effective than traditional individual loans, as these women used their solidarity and the group’s honor to get them through difficulties. Over time, the concept spread to developing countries around the world. After a time, the for-profit banking sector decided to look into the micro-credit market. With these banks came predatory lending. Before long, Yunus’s original concept was attracting major criticism. (If you’re having a hard time imagining what microcredit is like, think of Kickstarter. If a group of you wanted to get together and produce some new tech toy, you could put a pitch on Kickstarter and get micro-loans from strangers on the internet so you’d get your prototypes made.)

Heifer International

Another approach to development has been the Heifer International model. Starting in the U.S. in the 1940s, the idea was to send livestock to poor people in other countries, so they could live off the milk and eggs. They have also offered recipients agricultural assistance. Usually you see their brochures around Christmas time, where you can send in $20 to pay for Heifer giving a family a flock of chicks to raise, or send them $120 for a goat. As their founder said, after seeing too many hungry children, “These children don’t need a cup [of milk], they need a cow.” It seems so sensible, right?

But–imagine your poor family was given a flock of chicks by Heifer! All went well with their egg business, until the week when the chickens stopped laying and the family was getting hungrier and hungrier. Soon those chicks would be dinner. So Heifer has been putting more emphasis on the self-help-group model that Yunus pioneered. They have also partnered with BRAC.

The BRAC model

Founded in Bangladesh in 1972, BRAC is one of the biggest nonprofits in the world devoted to raising some 100 million people out of poverty. Their approach is sensible: test your projects to see if they are actually effective, focus on traditionally-underserved women, take into account the various ways poverty handicaps people, etc. But BRAC has been effective, in part, because a lot of previous organizations simply assumed their projects were effective. BRAC evaluates. So, like the original Heifer projects, they do offer participants livestock, but they also give training and income support for a long enough period that the recipient isn’t forced to eat their capital.

Evidence-based development planning wins the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2019

Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee of MIT and Michael Kremer of Harvard were jointly awarded the economics Nobel in 2019 for their work in development science–precisely for treating development programs as a science, and not as a ‘good intentions are everything’ kind of field. If you want to know the best way to boost students’ school attendance, take a few popular approaches and test each one out with a control group and pick the winner. If you discover parasitic worms are the key reason that children miss school, create a few programs to encourage parents to get their children dewormed and see which is most effective. If you are going to distribute bed nets to reduce malaria, test out what approach will be most effective. Should you give them away for free, or charge a small amount? (One study found that paying a small fee for the net did not improve utilization, which seems to run counter to economic logic!)

While it’s taken a long time for economists to arrive at “evidence-based” development policy–it’s definitely here to stay…which is a good thing.

It also means that many of you should go into evidence-based development policy and try to make a difference in this world!

Some Useful Materials

Watch a video about why some countries are rich and others poor.

A critique of the “why poverty?” approach of the 2024 Nobel winners.

The farm to factory to office model of development may be over: new paths are important.

Watch a video about the pros and cons of globalization.

A great source for data to use to compare the standard of living in different countries.

Listen to (or read the captions as her accent is thick!) Nobel Prize-winner Esther Duflo talk about using the experimental approach to development planning.

Read about microfinance: Mara Kardas-Nelson, We are Not Able to Live in the Sky: The Seductive Promise of Microfinance.

Cash assistance is best, researchers have found.

Media Attributions

- Savings club, Liberia is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Five-income-distributions-national-poverty-and-IPL-2_8633 © Joe Hasell is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- dissatisfied-vs-income_3000 © Max Roser is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- population-and-demography © United Nations, World Population Prospects is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- rigorous-and-impartial-public-administration-index © V-Dem is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- gdp-per-capita-maddison © Maddison project database is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license