16 Money: What It Is and How It Works

Bettina Berch

Consider this

Paper money seems so flimsy and worthless compared to copper axeheads:

Cowrie shells were used in trade from the 14th century onwards, not only in west Africa but across Asia, and in the Americas.

The 19th century King Gezo, of Dahomey (modern day Benin), was said to prefer cowries over gold! Would you?

We have been discussing finance by describing various financial instruments (stocks, bonds, etc) used to funnel savings into capital investments. It’s time we talked about the most basic form of finance, the kind we use in day to day life: money. Our definition of money, however, should give you a clue that it’s not just the paper in your pocket: Money is the set of assets that people use to buy goods and services from others.

Barter

There’s an old story that scholars from Aristotle to the modern day have told their students–that before we had money, people used barter. Barter is when people exchange actual goods or services with each other, without using money. Father-of-economics Adam Smith imagined a simple community where a baker wanted some meat from the butcher, but the butcher didn’t need bread, so the transaction couldn’t happen. Barter requires a double coincidence of wants: I need to want what you have extra, and you need to want what I have extra–or the deal doesn’t happen. In a small village, where we all knew each other’s business, barter might work most of the time, since we all knew what each other produced. I could count on getting an extra dozen eggs from you, for a quart of my goat’s milk. As the village grew larger and people no longer knew each other’s surplus–barter might not work. I wouldn’t know who would need my goat’s milk or what they might have that I wanted. The solution? Money. I go to the market, sell my goat’s milk for some coins, and I use those coins to buy eggs. Money is so simple!

This story of the origins of money in the breakdown of barter is pretty convincing–but it simply isn’t true! As anthropologist Humphrey explains, this has never happened anywhere in the world! In many cases, it’s the other way around–money gives birth to barter! After the fall of Rome, Roman coins were not as valuable as actual meat and eggs, so barter happened. When hyper-inflation causes economic break down, exchanging actual goods with others may work better than using paper money that’s losing value as you chat. Apart from these disaster scenarios, there are other situations where goods are exchanged but money is not used–gift cultures, potlatches, and hippie gatherings come to mind!

The functions of money

Even if barter might follow after money, rather than preceding it, in the modern world most of us use money. Let’s look at the three basic functions of money. First, money is a medium of exchange. It’s what you give someone when you want to purchase their goods or services. Second, money is a unit of account. When companies sell their goods online, they post their prices in money of some kind–dollars, euros, bitcoin, whatever. Third, money also functions as a store of value, transferring purchasing power from now to some future time. You get paid on Friday, you can spend some, and put some aside to spend next month. Is money a perfect store of value? No. The $20 bill under my mattress will lose purchasing power if it stays there for decades. But money is a better store of value than many other things–get paid in bananas, for example, and they will rot if you don’t eat them quickly.

The three kinds of money

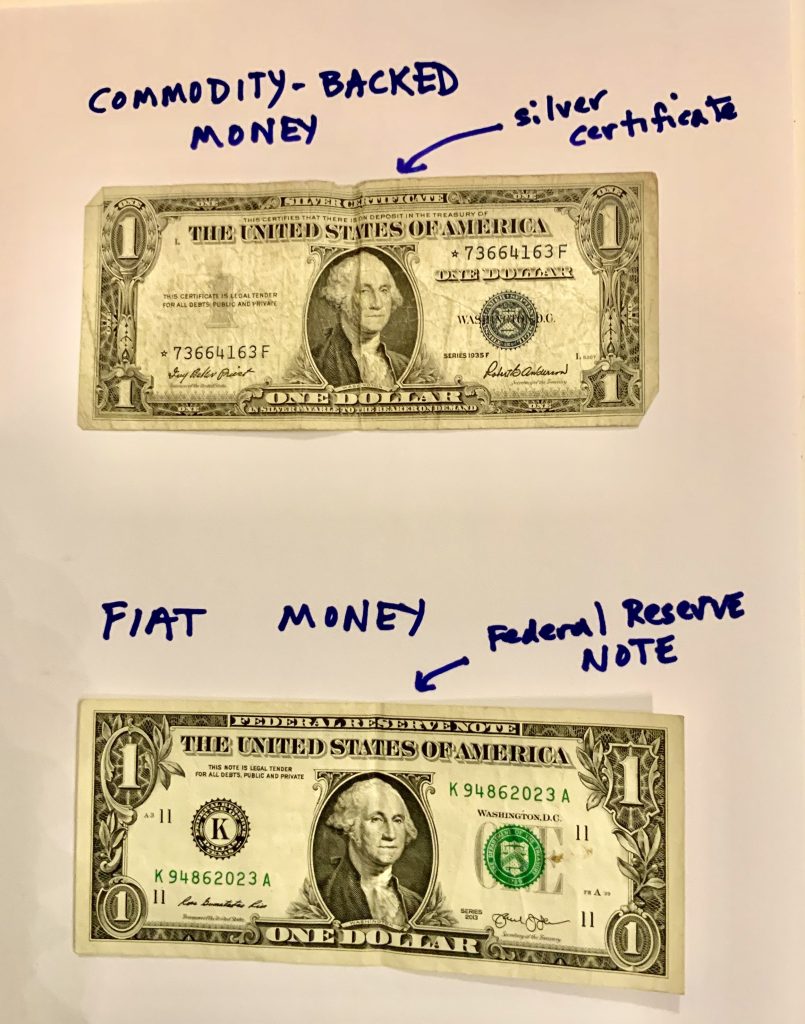

There are three basic categories or kinds of money: commodity money, commodity-backed money, and fiat money.

When your medium of exchange is something you could actually use, that’s commodity money. In an exhibition at CUNY in 2019 titled “Mediums of Exchange,” artist Agnieszka Kurant’s “Currency Converter” displayed shelves of items used as money in various parts of the world: salt, tobacco, Tide detergent, postage stamps, vacuum-packed fish, and even sacks of clean urine. In prisons, cigarettes used to be used as commodity money until smoking was banned. Now vacuum-packed mackerel is a commodity-money (apparently imprisoned Sam Bankman-Fried traded “macs” for a haircut) and so are ramen noodle packages (made famous in Orange is the New Black). Gold and silver bars or coins could also be considered commodity money.

Commodity-backed money is currency that can be exchanged for gold or silver. In the United States, we called our modern ones ‘silver certificates,’ which we stopped printing in 1964, and stopped redeeming for silver in 1968. Now we have ‘Federal Reserve Notes,’ which is fiat money. Fiat money is not backed by anything but the good faith we have in the government issuing it. (“Fiat” means “let it be done,” an edict or a law.)

There are many people who think they’d be happier with a pocketful of silver, rather than a wad of Federal Reserve notes–but let’s think about that. In 17th and 18th century England, a person would be hanged or burned at the stake for the crime of ‘clipping coins.’ This capital crime involved taking a gold or silver coin and clipping a bit off the edges of it, saving up a quantity of clippings, melting them down and making new coins. This crime was only possible because the coin edges were rough, so it was hard to tell if the coin you received was full weight or not. All that changed when minters developed a special ridged edge for new coins, sometimes inscribing ‘decus et tutamen,’ Latin for ‘an ornament and a safeguard’ around the circumference:

The clipping problem was solved…but it makes you wonder. Maybe King Gezo was right to prefer cowries, which he was able to evaluate, over nuggets of gold, which might be harder to assess.

The money supply: organized according to its liquidity

Economists divide up and then measure the money supply–all the different forms monetary assets can take– according to how liquid that particular form of money is. ( Liquidity refers to ease of use, ‘spendability.’) Cash is the easiest form of money to spend. You can pay for a coffee at the corner food truck with cash, no problem. You can spend it at the grocery store, no questions asked. This most liquid form of money is called M0 (pronounced M-zero).

The next-most liquid form of money would be a debit card or a check–neither one is as liquid as cash, but they’re definitely spendable. Look at it this way: the coffee truck will take cash, but won’t take your debit card because they don’t have a machine to swipe it. But if you went to the grocery store, they’d accept your cash and they’d also take your debit card (and even your check if you lived in a small town). So forms of money that draw on your checking account, plus everything in M0, are called M1.

Let’s think about your savings account. The coffee cart can’t accept your savings account statement as payment. What if you handed it to the grocery clerk? They’d tell you to go to the bank, get your money and come back and pay! Savings accounts are less liquid than checking or cash, so they’re the basis for M2.

Finally, we get to M3, which includes M2 and all kinds of accounts that make accessing your funds complicated (an IRA, a 529 college fund, etc) and/or charge you penalties for withdrawing before maturity.

After organizing the money supply into various liquidity tiers, economists track the size of the subset they find most significant, and then argue about policy. We won’t do that here, but let’s try using some actual numbers to understand money better. Let’s take the size of the total money supply and divide it by the number of people in the country. That should give us a rough idea of how much money each of us is holding, on average. If we take a roughly current estimate of M1 (cash+ checkable deposits) and divide by a roughly current figure on the number of Americans over 19 years old, we’d get $5,742 per person. You might find that number a bit high–after all, how many of us are holding almost $6000 in cash + checking accounts?

Once again, we might be having a problem with a ‘per capita’ figure– it’s an average, and an average can hide the fact that some people are 24/7, 100% cash. Some of those are the unbanked, but there are also some high-net-worth folks who are all cash as well—the ones engaged in illegal activity. Another reason you and I don’t have $5,742 of M1, might indicate a problem with the denominator, Americans over 19 years old. There are a lot of people around the world holding U.S. dollars as well–people in countries with hyper-inflation, stashing dollars when they can, people in war-torn countries keeping some getaway money, etc. If we added some of those folks into the denominator, we’d have a much smaller per capita amount of M1.

How banks increase the money supply

As we’ll see in the next chapter, the Federal Reserve is in charge of the size of our money supply. They use their tools and work with the banking system to reach the targets they’ve set. Let’s see how that works.

In many countries in the world today, fractional reserve banking is the rule. With fractional reserve banking, when you deposit money in your bank account, the bank sets aside, or reserves, some percentage of your money, and loans out the rest. In the U.S., it’s the Federal Reserve that determines that percentage, and for much of U.S. history, up until 2020, they required 10% of most kinds of deposits to be kept in reserve. This meant banks could loan out 90%. If a bank paid you 1% interest on the money you deposit, and they charged a borrower 15% interest on 90% of your deposit–you can see how a bank makes money! (That’s before they learned they could charge fees for everything, like a fee for telling you how much you had in your own account!) Still, a spread between interest paid on savings accounts and interest charged for loans could be true of any kind of banking. What’s special about the “fractional reserve” aspect?

Fractional reserve banking: the world before 2020

Imagine the Federal Reserve says banks have a 10% reserve requirement, and you deposit $100 in your account at Wonder Bank (not a real thing). The teller takes 10%–or $10– and puts it in the vault. The remaining $90 sit on the desk. Soon, your friend Jan goes to the teller and asks for a loan of $90 to buy a new copy machine for their business. The bank might loan them the $90 on the desk. Jan pays Forrest $90 for a new machine. Forrest goes to their bank and deposits Jan’s $90. Forrest’s bank puts 10% or $9 in the vault, and sets out $81 dollars to loan out. Stevo comes in to borrow as much as possible to set up a new business. The teller can loan him the $81 on his table. Stevo pays Izy to start paperwork for the business, and Izy deposits that $81 …

You get the picture. The original $100 deposit has been re-loaned over and over, but each time, that loan’s 10% less, because of the reserve requirement. In the end, that $100 deposit has turned into $1000 of spendable money. This is why we say that with fractional reserve banking, banks “create” money. It’s not that they print money–that’s done by the U.S. Treasury. But they create more of this money asset by the re-loaning of funds.

If this seems confusing, think of it another way. Imagine we had full reserve banking. You’d be taking your $100 deposit to the bank, and they’d put it in a drawer with your name on it. If you came back for your money, they’d just take it out of the drawer and give it back. The bank would be operating as a safe place for your dollars, or other valuables. While safeguarding was the role of medieval banks, it also explains why modern banks rent ‘safe deposit boxes’ to customers. You pay an annual rental and put what you want in safe-keeping. Notice–the pre-modern bank and the modern bank with safe deposit boxes–they both expect you to pay them. Because our modern fractional reserve banks can make money from the loaning feature, they pay savers interest.

If we assume that banks will try to loan out the full 90% of deposits they get, we can imagine there’s more money creation when the reserve requirement is 10% than if it were 50%. With a 50% reserve requirement, a bank would only loan out $50 of that $100 deposit. The loaning-out that followed would also be proportionately less. With a 10% reserve requirement our $100 turned into $1000. With a 50% reserve requirement, that $100 deposit would expand to $200. We call this expansion factor the money multiplier, which is defined:

Money Multiplier = 1 ÷ the reserve ratio

In other words, the money multiplier is the inverse of the reserve ratio. The higher the reserve ratio, the less money multiplying will be done through the banking system. Even if we assume that banks will try to loan out the maximum, they don’t get to set that maximum–that’s the job of our central bank, the Federal Reserve, which we’ll look at in the next chapter.

The world after 2020

In March 2020, the U.S. central bank, the Fed, reduced our reserve requirement to zero! This was partly in response to the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic. With widespread worries that no one could predict the impact a global pandemic might have on the economy, the Fed’s plan was to make sure the banking system had maximum liquidity. No qualified borrower should be turned away because a bank did not have enough reserves to loan out a bit more money. Setting the reserve requirement to zero, effectively cancelled the “money multiplier.” But don’t worry–the Fed had already created a few new tools which we’ll examine in the next chapter.

Still, you might well wonder, why do you still have to learn about the reserve ratio and the money multiplier, if we’re not using them anymore? Just because the U.S. joined a handful of other countries when it set a zero reserve requirement (UK, Sweden, Canada, Australia, Hong Kong, to name a few), there are a lot of countries that actively use a reserve requirement to this day. China, for instance, has been cutting its reserve requirement in response to a sluggish economy, but as of December 2023, it was still at 7.4%. And the U.S. Fed might re-instate a reserve requirement anytime it sees fit!

Some Useful Materials

Read about Marco Polo discovering the Chinese use of paper money.

Read about the myth of barter.

Watch a video about what money is.

Watch a short video on what banks do.

Watch a video on ramen noodles used as commodity money in prisons.

If you’ve ever wondered where words like ‘dollar’ or ‘money’ or ‘yuan’ or ‘pound sterling’ come from, listen to this podcast.

Media Attributions

- Axe money is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Cowrie Shells Used as Money is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Commodity-backed and Fiat money © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Screenshot-2024-03-31-at-8.42.31 AM © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Screenshot 2024-03-31 at 8.34.03 AM © Bettina Berch is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license